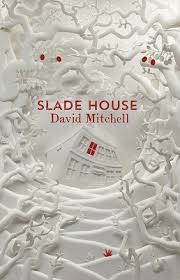

The events of this short novel begin in 1979, when Nathan Bishop and his mother Rita arrive at the eponymous Slade House in response to an invitation from its châtelaine, Lady Norah Grayer. Rita is there to play the piano at one of Lady Norah’s soirées. Nathan, a complicated, lonely boy, is shown the grounds by Norah’s son Jonah, who suggests they play a game of tag called Fox and Hounds. Slade House is hard to find – Nathan and Rita pass by the gate twice without seeing it – and the place seems frozen in time somehow, a faerie landscape too perfect to be true. In the manner of all decent fairy tales, this turns out to be the case. Norah and Jonah have an ulterior motive in inviting the Bishops into their domain. That neither of them get to leave would seem par for the course.

The events of this short novel begin in 1979, when Nathan Bishop and his mother Rita arrive at the eponymous Slade House in response to an invitation from its châtelaine, Lady Norah Grayer. Rita is there to play the piano at one of Lady Norah’s soirées. Nathan, a complicated, lonely boy, is shown the grounds by Norah’s son Jonah, who suggests they play a game of tag called Fox and Hounds. Slade House is hard to find – Nathan and Rita pass by the gate twice without seeing it – and the place seems frozen in time somehow, a faerie landscape too perfect to be true. In the manner of all decent fairy tales, this turns out to be the case. Norah and Jonah have an ulterior motive in inviting the Bishops into their domain. That neither of them get to leave would seem par for the course.

I’m nonplussed by Slade House, in pretty much the same way I was nonplussed by The Bone Clocks. You don’t have to have read The Bone Clocks to make sense of this book, although how much you enjoy it may depend on how much you enjoyed – or would enjoy – the earlier novel. We’re back in the land of soul vampires, of the eternally warring clans of Anchorites and Horologists. As in The Bone Clocks, the fantasy tropes Mitchell employs are of the most predictable kind, the most basic of base metals. That Mitchell chooses to essentially repeat his basic plot – an Engifted individual arrives at the house, finds their most earnest desires fulfilled, and then gets their soul sucked through a straw (kind of literally, actually) by devious semi-immortal twins – through the first four of these five interlinked short stories could be read as either daring or desperate, depending on your point of view. Oh, and then Marinus turns up. Whether this pleases you or pisses you off will, once again, be down to how deeply you’re in love with David Mitchell’s concept of the mega-novel and the characters that recur within its endlessly expanding galleries and corridors.

It’s a weird one, isn’t it? Would we even be talking about this book if it weren’t by David Mitchell? In terms of its invention and originality it is fairly weak beer. Mitchell has to employ vast tonnages of exposition to make sense of everything, and had this been the first manuscript Mitchell ever turned in I don’t think he’d have got all that far with it. But Mitchell is a part of our literary landscape now, and – as is inevitably the case when an author becomes enshrined in this way – everything he writes is considered to be interesting at some level.

Which Slade House – undoubtedly and against all greater logic – still is. What makes me draw back from giving this book an emphatic thumbs down is – as with The Bone Clocks – its glorious readability. There are slips and slides even here: Mitchell seems to have fallen into the habit of making everyone talk in Noughties Estuary, even when it’s not appropriate to the character in question (I don’t think the seriously posh Chloe Chetwynd would naturally talk about ‘legging it’, for example). Nathan Bishop is an engaging character and I enjoyed the chauvinistic cop Gordon Edmonds as I tend to enjoy all Mitchell’s bad guys. But elsewhere the characterisation tends towards the broad-brush – see the students in ‘Oink Oink’ in particular. It would be pedantic and boring of me to mention the ‘how can these narratives be possible when the narrator ends up dead???’ thing, though not mentioning it doesn’t mean it isn’t a problem. But Mitchell’s command of the English language is so effortless, so welcoming. Mitchell is a natural storyteller – you can’t help but follow where he wants to take you.

As a writer I have always felt a great affinity with Mitchell’s shopworn, 1970s-housing-estate Britain – I am deeply attached to Black Swan Green in particular – and there’s plenty of that on display here. I have serious criticisms of this book. It is difficult to understand how Mitchell’s cartoonish use of fantasy archetypes might be taken seriously – I think I’d be more sympathetic to the enterprise if the whole thing were a send-up, but I don’t think it is. There’s too much (cough) soul-searching for that, too much clunky tying-in of this story’s somewhat black-and-white morality with realworld politics. It’s all a bit of a junkyard. Some nice stuff here but what to make of it?

And yet (as with The Bone Clocks) I can’t help but admit I thoroughly enjoyed reading Slade House. How do you explain that, except by saying that by worming his way so deeply and so fatally into our subconscious, Mitchell is – like his Anchorites – still capable of genuine magic. Not sure whether to recommend this book or not. But I guess if you’re a Mitchell fan you’ll own a copy already.