I first became aware of the Arthur C. Clarke Award at the beginning of the 2000s, when I was starting to take a professional interest in what we like to call the field. Prior to that, I was vaguely aware that there was such a thing as the Clarke Award – I knew Margaret Atwood had won it, for example – but not of how it related to other awards and to critical discourse. I remember the announcement of the winner – Perdido Street Station – in 2001, largely because of the gathering interest around a certain up-and-coming young writer named China Mieville, but the first year I can recall taking an active interest in the award at the shortlist stage was 2003. Two of the novels on that shortlist – Christopher Priest’s The Separation (Chris and I didn’t meet in person until 2004 but I’d been an admirer of his writing for years) and M. John Harrison’s Light – were key works for me, novels from what I might loosely have termed ‘my’ science fiction. I was interested to see how the battle between them would play out. Also on that shortlist was The Scar, which I still consider to be Mieville’s finest novel to date. These were big hitters, big books. The Clarke was clearly an award to take note of and I was officially hooked.

I first became aware of the Arthur C. Clarke Award at the beginning of the 2000s, when I was starting to take a professional interest in what we like to call the field. Prior to that, I was vaguely aware that there was such a thing as the Clarke Award – I knew Margaret Atwood had won it, for example – but not of how it related to other awards and to critical discourse. I remember the announcement of the winner – Perdido Street Station – in 2001, largely because of the gathering interest around a certain up-and-coming young writer named China Mieville, but the first year I can recall taking an active interest in the award at the shortlist stage was 2003. Two of the novels on that shortlist – Christopher Priest’s The Separation (Chris and I didn’t meet in person until 2004 but I’d been an admirer of his writing for years) and M. John Harrison’s Light – were key works for me, novels from what I might loosely have termed ‘my’ science fiction. I was interested to see how the battle between them would play out. Also on that shortlist was The Scar, which I still consider to be Mieville’s finest novel to date. These were big hitters, big books. The Clarke was clearly an award to take note of and I was officially hooked.

One of the central reasons the Clarke became so interesting to me is that it is a juried award. Nothing involving human beings can ever be entirely objective, but the presence of a jury – a panel of persons selected for their ability to be impartial and for their knowledge of the field – does at least suggest a level of discipline, critical acumen and meaningful debate that should but rarely does pertain to fan awards. At the simplest level, only a vanishingly small number of fans – now so more than ever – can ever hope to come close to reading all the books – or even all the critically relevant books – in contention for an award, which means that very nearly everyone voting, and this includes you and me, will be voting from a position of partiality right from the start. Add to this the ease with which fan-voted awards can be gamed – the Sad and Rabid Puppies being merely the most recent perpetrators of such shenanigans – and you end up with something that is practically worthless in critical terms, and only rarely approaches a broad consensus of what ‘most’ fans ‘like’. Add to that the sheer tininess of some of the committed voting pools – the BSFA Award for example often has fewer than 150 people voting – and the picture looks even bleaker.

The critical discourse around fan awards also tends to be lacklustre. In 2015, for example, it centred almost entirely around the Sad and Rabid Puppies campaign, and not in a good way. Instead of focussing on the terrifyingly poor quality of many of the shortlisted works – which would at least have provided some amusement, not to mention more than sufficient reason to prompt those blanket No Award votes in and of itself – criticism rapidly polarised into mostly unexamined, gloves-off prejudice on one hand, self-righteous faux-indignation on the other. Such polemic quickly becomes repetitive and predictable and is ultimately meaningless. It is as morally easy to be outraged by the bigoted (and ludicrous) pronouncements of Vox Day as it is to despise the buffoonery (and bigotry) of Donald Trump. It is not so easy, apparently, for us to have a conversation about the greyer areas of SF politics: the ostracism of individuals for expressing contentious views, the log-rolling openly engaged in by writers you like and whose work you admire, the cliques and hierarchies that do exist, in publishing as well as fandom, the edging aside of rigorous critical discourse in favour of mutual back-scratching and social approbium.

As a juried award, the Clarke Award is not subject to such indignities. As a juried award for the ‘best science fiction novel’ of the given year, it should have critical value, not simply in selecting a single title but in generating conversation and debate among readers and critics: what constitutes science fiction, what are the issues currently at stake, what is ‘best’? A literature exists in symbiosis with its critical hinterland, and, it seemed to me when I began taking notice in 2003, the Clarke Award was well placed to form a kind of central axis around which British science fiction might revolve, a critical hub, if you like. Added to that, it was ours – named for a British writer and indisputably British in tone, even as it opened its borders to books from all nations. This is why I became interested in it, and why, sometimes against my better judgement, I remain interested in it still. I care much less about which book actually wins than the critical process by which the selection is arrived at. I like the talk.

The Clarke Award is thirty this year, and when I was invited to be on a panel at Eastercon to commemorate and discuss this anniversary, I was happy to accept. In the brief for the panel, we were encouraged to consider ‘the influence of the award, the story the list of previous winners has to tell about SF in the UK, and how the award’s place in the field has changed over time’. A lot to think about then, and in making my own mental preparations for the panel I began by asking myself, prior to examining the documentary evidence in any way, how I thought the Clarke had evolved over time, what kind of changes I thought I’d see reflected, were I to look at the figures.

The biggest change I thought I was going to see was an increasing representation of so-called literary SF – that is, science fiction written by writers normally considered to be part of the literary mainstream, or published by non-genre imprints – among the shortlists as we approached the present day. When Margaret Atwood first won the Clarke Award back in 1987, her publisher, Faber & Faber, weren’t at all keen to have The Handmaid’s Tale entered for the award in the first place. Atwood herself seemed conflicted about what SF actually was and whether or not she wrote it, and there was a more than minor backlash against Atwood’s win amongst critics, fans, and even some of the judges. Compare that with this year, when Margaret Atwood attends the awards ceremony for The Kitschies wearing a tentacle-themed hair ornament, when more mainstream writers than ever before are experimenting with science fictional tropes and ideas they wouldn’t have been seen dead near thirty years ago, when science fiction has burst out of the geek ghetto to become mainstream entertainment. Last year’s Clarke Award was won by Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven, an almost universally popular novel from a devoutly literary imprint (Picador) and that was also a finalist for the National Book Award. Such a seismic shift in attitudes would surely be backed up by statistics.

As regards the question of gender and ethnic diversity, I felt less sure. Memory alone was telling me that the number of shortlistees from minority and non-Anglophone backgrounds has been vanishingly few. As for gender parity, I had the feeling that in spite of much talk and bluster on the subject, things hadn’t changed all that much on the ground. I had the idea in my mind that in terms of more diverse representation, the Clarke was lagging far behind mainstream literary prizes such as the Booker and the Costa, which had, I felt, begun to be more inclusive from way back.

What I actually discovered when I looked at the statistics was that of the twenty-nine winners to date, just six (Margaret Atwood, George Turner, Marge Piercy, Amitav Ghosh, Jane Rogers and Emily St John Mandel) have been drawn from the literary mainstream. Perhaps even more surprising is the spread. I set out thinking the number of shortlisted books from mainstream imprints would have increased particularly during the past decade – the decade of popular genre-busting novels like Cloud Atlas, The Time Traveller’s Wife and Never Let Me Go, all of which were shortlisted for the Clarke. Whereas in fact the number of non-genre SF shortlistees has remained pretty consistent and pretty low, with no more than one or at the most two mainstream titles making it to the shortlist in any given year (a bias strikingly reaffirmed in this year’s selection, possibly the most disappointingly core genre shortlist of the decade so far and certainly since 2012). The two exceptions to this rule came in 2008 and 2013, when a fifty-fifty split between genre and mainstream imprints brought forth a predictable spate of discontented rumblings from the genre heartlands. (Just to be clear: of course Ian McDonald’s Brasyl was an egregious omission. Personally I think it’s egregious and downright weird that, as one of the most technically adroit and imaginatively fecund SF writers currently working, McDonald hasn’t so far won the Clarke. But that doesn’t mean that Sarah Hall’s The Carhullan Army – voted best science fiction novel by a woman of its decade by readers of Torque Control – should be looked at askance as some kind of dangerous infiltrator just because it happens to be published by Faber & Faber.)

So while the boundaries are pushed just about far enough to satisfy the iconoclasts, the Clarke remains determinedly an award of the genre heartlands, often drawing again and again from the same smallish pool of well established writers (of all the writers ever shortlisted for the Clarke, 29 have placed twice or more). This could in its turn have some bearing on the issue of gender parity, which has remained decidedly skewed in favour of men. While 11 out of 29 winners have been women (12 if you count Pat Cadigan’s double), from a total of 181 possible shortlist places over the 29 years, just 51 have been occupied by women. In only 5 years (1993, 1995, 1998, 2002 and 2015) was gender parity achieved on the shortlist, and I was particularly shocked by the number of years – 10 – in which only one woman was shortlisted.

There has never been a year when the number of women on the Clarke Award shortlist has exceeded the number of men.

Turning to the issue of ethnic diversity, the statistics are predictably embarrassing. Out of 181 shortlist places, just 7 have been filled by writers who are black, Asian, minority ethnic or from non-Anglophone backgrounds. This figure speaks for itself: the Clarke Award’s demographic continues to be mostly white and mostly male.

Following up on my theory that the Booker Prize would show greater diversity in terms of race and gender, I was neither wholly right nor completely wrong. In terms of ethnic spread, the Booker does a little better than the Clarke in that of the 171 shortlist places available between 1987 and 2015 (the same period as the Clarke Award’s existence, in other words) 33 were filled by black, Asian and other minority writers, more if you count multiple nominations for Salman Rushdie, Kazuo Ishiguro and Rohinton Mistry. It’s worth bearing in mind that as a fraction of the whole this is only about one fifth, and when it comes to gender parity the results are hardly inspiring. Out of 29 winners, just nine have been women (10 if you count Hilary Mantel’s two wins), and as with the Clarke, the spread of shortlistees displays a wide disparity. Of the 171 shortlist places, just sixty were filled by women. While gender parity on the Booker shortlist has been achieved six times (in 1987, 1989, 1990, 1996, 2009, 2012) and with women even exceeding the number of men on three subsequent occasions (2003, 2006 and 2013) this is counterbalanced by the eight years (1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998, 2004, 2008 and 2011) in which only one woman appeared on the shortlist.

It would appear that the Booker Prize is almost equally conservative in terms of diversity as the Clarke. This doesn’t reflect well on either, but it does at least prove, in a backhanded way, that the Clarke isn’t as hidebound as it could have been.

This is not to level accusations of bias at the Clarke as an institution or at its jurors. The problems of systemic bias begin much further back, at the point of entry to the industry and even before that. The Clarke submissions list is the end point, the point at which we see the results of such bias at work, and of course the judges can only judge the books that are submitted – for a further example, see the recent controversy surrounding the all-white line-up for World Book Night. The problems experienced by women, people from working class backgrounds, people from minority ethnic backgrounds and other marginalised communities attempting to enter the literary field will come from above and from below and work in circular motion. For anyone still unsure of why this matters, I would advise them to begin by reading a recent piece by the translator and publisher Deborah Smith. Her insights into how diversity actively promotes literary excellence are astute, timely, and succinctly worded and I cannot recommend her article highly enough. For science fiction readers, writers, critics and Clarke jurors on the ground, I would suggest the main task currently is to make ourselves aware of the situation and to take notice of what writers from disadvantaged communities are saying. For British science fiction, a more diverse landscape of literary works is pretty much essential for the evolution and continuing health and relevance of the genre. The Britain we inhabit now is not the Britain of the 1950s, nor even the Britain of the 1970s New Wave. We need to see the changes that are happening in reality reflected in the literature we produce and consume, which means hearing voices and opinions from all sections of our society. A retrospective SF is a fossilized genre is a dead literature. If I am excited by writers such as Helen Oyeyemi and Sunjeev Sahota and Xiaolu Guo within the literary mainstream, I desperately want to see their equivalents in British science fiction, and by extension on the Clarke Award shortlist.

Which then brings us on to the question: what is the Clarke Award for and who is it aimed at? On the face of it, the answer is simple: the rules of the Clarke as laid down by Sir Arthur C. Clarke, the Award’s founder, and the committee that originally set up the award stated that the ACCA should be awarded to ‘the best science fiction novel published in Britain in the given year’, the aim being to promote science fiction to a wider public, and to reward excellence within its remit. So far, so uncontroversial. But anyone who has had anything to do with the science fiction community will know that science fiction fans – not to mention writers and critics – thrive on controversy (some might call it nit-picking) and habitually find it more or less impossible to agree amongst themselves on what constitutes science fiction, let alone best.

From the moment the award was inducted, there was in-fighting between various sections of the community as to which novels and which writers should be voted on to the shortlist. In the run-up to our Eastercon panel, the critic Edward James shared with us a highly informative essay he wrote as a contribution to the volume Science Fiction, Canonization, Marginalization and the Academy (eds Gary Westfahl/George Slusser Greenwood Press 2002), ‘The Arthur C. Clarke Award and its Reception in Britain’, describing, amongst other things, his experiences as the Award’s first administrator:

“Should the Award go to a work which the judges recognise to be solidly within the science fiction tradition, which would no doubt be applauded by SF fans, but received blankly by an uninterested world? Or should the Award associate itself with a work that the outside world would actually recognise, to increase the standing of science fiction by hanging on the coat-tails of recognised Literature?”

James writes, thus posing the question that has divided juries and characterised the discussion around the award for the whole of its run. In 1987 the battle seems to have been between those rooting for Margaret Atwood for The Handmaid’s Tale and those insisting that Samuel R. Delany should take the award for Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, a ‘proper’ science fiction work from an acknowledged master of the genre. “It was not an auspicious start to the Award,” James continues. “In retrospect, The Handmaid’s Tale was the wrong book.” This written in 2002, before Atwood wrote her Maddadam trilogy and long before she turned up in London wearing a tentacle on her head. Whilst admitting that The Handmaid’s Tale was ‘a very good book’, James positioned himself firmly in the Delany camp at the time and seems not to have substantially changed his opinion by the time he wrote his article fifteen years later.

A similar scandal rocked the Clarke just six years later in 1993, when the judges decided to exclude Karen Joy Fowler’s now classic Sarah Canary from the shortlist on the grounds that it was ‘not science fiction’, then went on to compound the controversy still further by eventually awarding the prize to Marge Piercy for Body of Glass, another work from a literary publisher that was deemed unworthy of the award by some sections of the SF community: Piercy was not British, and moreover she was already a successful mainstream writer who did not need the prize money or the publicity. The critic and former Clarke judge (part of the jury that awarded the prize to Atwood, in fact) John Clute threw himself into the fray, declaring that ‘the decision was so bad my ears must have deceived me’:

“Body of Glass fatally gives off that gingerly feel one often detects when a mainstream author is manipulating SF devices and scenarios to illuminate her own concerns.”

Boo, hiss. Emotion, subjective viewpoint and personal odyssey in science fiction, whatever next?? I don’t think Clute would mind me having a bit of a dig here, most especially since he has recanted these vows more or less completely in the meantime, becoming as he is now a veritable mainstay of the inclusive camp. But the above quote is inestimably useful as an illustration of core science fiction ideology, which persists in this exact formulation to this day and to this hour. If Clute has moderated his approach, there are plenty who haven’t, and so the war rages on.

The most notable Clarke meltdown of the current decade must belong to 2012, remembered in some quarters as Priestgate. The most immediate and lasting effect of Priest’s polemic – something that was often overlooked in the welter of counter-rhetoric surrounding it – was that it attracted a huge amount of attention for the award. Indeed it could be argued that Christopher Priest’s essay ‘Hull 0: Scunthorpe 3’, bemoaning the quality of the 2012 shortlist in general and the alleged incompetence of the jury in particular was largely responsible for the wave of interest and popularity the Clarke began to enjoy in the mainstream press. The forthrightness of Priest’s pronouncement was treated as shocking in some quarters, and came in for considerable criticism as a result. Nonetheless, anyone reading his essay today will see that his analysis of the books remains astutely on point, and whilst no blame should be attached to individual judges – the idea of a word as strong as ‘blame’ being associated with something as ephemeral and subjective as the shortlist for a literary prize is faintly ridiculous in any case – the fact remains that the 2012 Clarke shortlist could be held up as one of the most potent examples of what can happen when the judging panel has no clear or united vision of what they are looking for – of what is ‘best’ in ‘science fiction’. The 2012 shortlist, more now even than then, looks like a classic botch job: a set of random compromises, the result inevitably arrived at when five individuals of differing tastes and mixed critical abilities fail to form a coherent vision and resort instead to horse-trading, and it was hardly an act of literary terrorism for Priest to point that out. I might add that if only all Clarke shortlists generated polemic this sophisticated, this concerned with literary values and the inherent potential of science fiction to be radical and progressive (as opposed to retrograde and derivative) our awareness of what the field is doing, not to mention the field itself, would be mightily the better for it.

In all fairness to the jury, it would not be difficult to mount a similar tale of woe for any year – there’s not a single literary award shortlist that doesn’t sport at least one glaring omission or freakish inclusion. The judges are only human, after all, and each will come to the table replete with their own prejudices, preconceptions, and hard-wired preferences. Take a look at this fascinating retrospective by Booker Prize jurors, and you’ll quickly see that the chances of any of them being persuaded out of their pre-formed opinions is questionable, to say the least. Unless judges are lucky enough to find themselves sitting on a jury of uncannily like minds, the shortlist for any prize, not to mention the winning entry, will continue to be something of a lottery, the hard-won result of in-fighting, barely suppressed professional rivalries, occasionally pure cussedness. Speaking for myself, the science fiction I admire most could be categorised as a mixture of literary postmodernism, subjective hyperrealism, advanced and/or experimental structure bound together with speculative elements. I am the kind of reader and writer who believes that the old kind of space fiction – intergalactic empires and people setting off in rockets to conquer the stars with no more than a tangential connection to lived or indeed scientific reality – is usually not worth bothering with in critical terms, that the core SF tropes are only interesting as literature if they are subverted to such an extent as to make something entirely different. I happen to believe that when placed next to the linguistic and metaphysical glory that is M. John Harrison’s Kefahuchi Tract trilogy, something like Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch trilogy, though competently executed and entertaining on its own terms is revealed starkly for what it is: linguistically unspectacular, thematically redundant and completely lacking in literary irony.

When Edward James says in his paper that he considers Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand to be one of the greatest works of science fiction so far written, I would agree with him heartily. When he insists that Delany’s work would be ‘largely impenetrable to outsiders’ – outsiders who have not been ‘initiated’ into the shorthand, language and conceptual frameworks of science fiction, I would beg to differ. For me, Delany is not just a great science fiction writer, he is a great writer full stop, and SIMPLGOS would be no more difficult for the general reader than any other work of modernist or postmodernist literature. It is – like Woolf or Beckett or Foster Wallace – simply a text that requires a modicum of concentration. Truly great science fiction – that is, science fiction that pays attention to itself in terms of literary values – needs no special pleading. Indeed I would go a lot further than this. I would suggest that if a work of science fiction cannot stand next to works drawn from the mainstream and hold its own in terms of literary values, we need to be asking ourselves if it is truly great.

I am aware that this view is contentious. I know there will be many who disagree with it violently, attesting that it is attitudes and tastes like mine that are destroying science fiction, stripping the field of what makes it unique and worthy of specialist discussion in the first place, and I respect that. I am even prepared to admit they may have a point. I want the old guard to go on fighting because debate is the lifeblood of culture and because it is vitally important that the critical conversation around the Clarke Award be revitalised and strengthened. For if there is a threat to the continuing success and popularity of the Clarke Award, it seems to me that the danger lies in critical apathy. In the four years since Priestgate, rigorous online discussion of the shortlists seems to have nosedived and atrophied, culminating in a situation where last year, for the first time in a long time, there was no comprehensive critical review of the Clarke Award shortlist at Strange Horizons and, because of inept programming and yet another shift in the timing of the award, no discussion of the shortlist at Eastercon either.

At least a part of the problem resides in the fact that there is no recognised online ‘hub’ for British SF. For a number of years (from 2009 when the submissions list first started to be released), the submissions list was announced via the BSFA/Vector blog, Torque Control, where lively, informed discussions of many critical and ideological aspects of SF took place under the dedicated, engaged stewardship of Niall Harrison. In 2009, the post announcing the Clarke submissions list generated 112 comments, mainly debating the eventual shortlist and offering guesses. The following year saw an almost equal number of comments and shortlist guesses, surely a sign that interest surrounding the award was in rude health.

With the departure of Niall Harrison to take up the post of editor-in-chief of Strange Horizons, the Torque Control blog became a graveyard almost overnight. Since 2013, the submissions list has been put out to tender, firstly at SFX, which has always been a media rather than a literary publication, and this year at Medium, a major online publishing platform to be sure but one that has little to no direct connection with the British science fiction community. To date, the Clarke submissions post has generated precisely three comments, only one of which could be counted as discussion of the books or possible shortlist.

When you compare this lacklustre response with the proliferation of enthusiastic and knowledgeable blogs, shadow-panels and discussion forums associated with mainstream literary prizes such as the Man Booker International, the Baileys or the Booker itself it looks pretty pathetic, especially given that it always used to be the other way around.

One of the issues that was discussed on the Clarke anniversary panel was the absence – for two years in a row now – of the traditional ‘Not the Clarke Award’ discussion from the Eastercon programme. This lively and popular item in which panellists discuss the shortlisted books in the manner of a shadow award jury has always been a crowd-puller, and in the past the announcement of the Clarke Award shortlist has always been timed to allow for it to take place. In 2015 and 2016 the date set for the announcement of the shortlist has taken no account of Eastercon. Whilst it would be wrong to suggest that the Eastercon membership represents anything approaching the whole of the British science fiction constituency, this decision to discount it entirely does appear to be yet another missed opportunity for informed critical appreciation of the Clarke Award, as well as showing a general lack of consideration for the fanbase. Even if it does not represent the whole of the constituency, Eastercon probably does qualify as the largest gathering of BSFA members in one place during any given year. With the BSFA as one of the three organisations at the constitutional heart of the Clarke Award this surely has to count for something. Such a slap in the face for fandom might be easier to tolerate were there a genuine reason for the change. With the lack of transparency around this question currently in force, these decisions – like the earlier decision to take the submissions announcement away from Torque Control – appear completely random and pointless, not to say actively deleterious.

Another issue raised by the panel was the question of a longlist. There can be absolutely no doubt that the decision taken in 2001 by the organisers of the Booker Prize to start publishing a longlist has been of immense value in extending and intensifying the discussion around both the prize itself and literary fiction in general. The reasons for this – more books to discuss over a longer time period – should be obvious to anyone. To my mind at least it would seem equally obvious that the idea of introducing a longlist to the Clarke Award calendar is pretty much a no-brainer. In the brief discussion on Twitter (March 27th) that followed this year’s Eastercon panel, the award’s director Tom Hunter had this to say on the subject of introducing a longlist stage to the award:

I prefer our full submissions list to a longlist. If we had more time/resource I would personally prefer to do more of something else than just more lists. For me a longlist doesn’t really create anything new, just an interim list, and it’s a big extra task to create for little return.

When asked by SF critic, blogger and previous Clarke Award juror Martin Petto why we can’t have both – it having been made clear during the panel by the current chairman of the Clarke jury Andrew M. Butler that far from it being a ‘big extra task to create’, the judges are already in the habit of drawing up their own unofficial longlist for the purposes of discussion in any case – Hunter responded:

But it’s not a longlist, it’s a discussion list. Longlist implies these are best not the ones we’re still talking about.

Quite apart from the problem presented by Hunter’s apparent underestimation of a longlist’s potential in terms of the discussion and promotion of a wider pool of books and writers, it would seem logical to argue that ‘these are [the books] we’re still talking about’ precisely because these are the ones we think are ‘best’ (by whatever definition arrived at by individual jurors) at that stage. Why else would be jury be discussing them? Hunter’s argument, such that it is, seems like something of a double negative.

On the demise of Torque Control as a forum for discussion, Tom Hunter had this to add (March 29th):

[The BSFA site] is a hub I’d say, but no matter how many there are people always seem to want more. Was Torque Control ever really main BSFA product? More good initiative by a member [Niall Harrison] now doing great stuff for Strange Horizons. It was a product formed around a person thus hard to replicate even if you wanted to. And thus BSFA shouldn’t try to replicate that old energy even if people miss Torque Control as a hub. It was what, eight years ago it was in its prime? Can’t help think things change.

Things change, indeed. And I would venture that it is exactly this kind of complacency (not to mention the inappropriate use of the word ‘product’) that makes them change for the worse. More proactive ways of harnessing greater critical involvement in the award might include instituting a discussion page at the Arthur C. Clarke Award website as a host platform for commissioned reviews and critical articles, roundtable debates of science fiction and its evolution as a literature, interviews with nominees and even – gasp – the initial announcement of the submissions list. At least then people would have a logical place to congregate. (Who knows – we might even decide to call it a hub…)

The current management of the Arthur C. Clarke Award appears to have forgotten that mere publicity is not the same as having a critical hinterland, that bland puff pieces and tick-box number-crunching are not the same as a discussion about literary values, that claiming any given shortlist as ‘great’, ‘exciting’ or even ‘diverse’ is shallow and pointless when that claim is not backed up with more rigorous discourse about the merits of the novels shortlisted and what exactly constitutes ‘great’ or ‘exciting’ or ‘diverse’. For the Arthur C. Clarke Award to survive as the beloved and respected and valuable institution it avowedly is, we need passionate critical engagement, we need personal involvement over a wide demographic. We need readers to feel excited by the idea of discovering new books, excited enough to want to talk about them afterwards. To argue about what is best and what is science fiction.

(NB: A significant portion of this essay was drafted prior to Eastercon. Any statistics quoted or referred to therefore do not include this year’s recently announced Clarke Award shortlist.)

The first indication that anything is wrong in the lives of the two sisters in Paul Tremblay’s 2015 novel A Head Full of Ghosts is when the older girl, Marjorie, begins telling scary stories. Meredith, known to everyone as Merry, is used to playing story-games with her beloved big sister, but she’s never heard anything like this before. Instead of adapting fairy tales in her usual manner, Marjorie tells Merry all about the Great Molasses Flood in Boston in 1919. When Merry, horrified, asks her if the story is something she found on the internet, Marjorie insists the details of the disaster were lodged inside her all along:

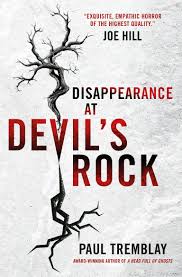

The first indication that anything is wrong in the lives of the two sisters in Paul Tremblay’s 2015 novel A Head Full of Ghosts is when the older girl, Marjorie, begins telling scary stories. Meredith, known to everyone as Merry, is used to playing story-games with her beloved big sister, but she’s never heard anything like this before. Instead of adapting fairy tales in her usual manner, Marjorie tells Merry all about the Great Molasses Flood in Boston in 1919. When Merry, horrified, asks her if the story is something she found on the internet, Marjorie insists the details of the disaster were lodged inside her all along: is that Tremblay’s new novel is hardly less impressive. Another moving portrait of family life, Disappearance at Devil’s Rock deals with the aftermath of the sudden and unexplained disappearance of fourteen-year-old Tommy Sanderson from a patch of local wilderness known as Devil’s Rock. Tommy was a good kid, popular with his friends and loved by his family. He was doing well at school, had no known problems with drugs or alcohol, and seemed to have a bright future ahead of him. The friends who were with him on the night he went missing initially have no explanation for what has happened, and it is down to Tommy’s mother Elizabeth and his younger sister Kate, both still in shock, to delve deeper into the mystery of Tommy’s recent private life. As pages from Tommy’s journal make increasingly disturbing reference to an older boy named Arnold, so Kate in particular becomes convinced that Tommy’s friends, Luis and Josh, must know far more about Tommy’s whereabouts than they are letting on. Meanwhile, Elizabeth investigates what she believes may be a physical manifestation of Tommy’s ghost. When the truth of what happened that night finally comes out, it is more tragic and more horrifying than anyone involved in the search has hitherto suspected.

is that Tremblay’s new novel is hardly less impressive. Another moving portrait of family life, Disappearance at Devil’s Rock deals with the aftermath of the sudden and unexplained disappearance of fourteen-year-old Tommy Sanderson from a patch of local wilderness known as Devil’s Rock. Tommy was a good kid, popular with his friends and loved by his family. He was doing well at school, had no known problems with drugs or alcohol, and seemed to have a bright future ahead of him. The friends who were with him on the night he went missing initially have no explanation for what has happened, and it is down to Tommy’s mother Elizabeth and his younger sister Kate, both still in shock, to delve deeper into the mystery of Tommy’s recent private life. As pages from Tommy’s journal make increasingly disturbing reference to an older boy named Arnold, so Kate in particular becomes convinced that Tommy’s friends, Luis and Josh, must know far more about Tommy’s whereabouts than they are letting on. Meanwhile, Elizabeth investigates what she believes may be a physical manifestation of Tommy’s ghost. When the truth of what happened that night finally comes out, it is more tragic and more horrifying than anyone involved in the search has hitherto suspected.