I’ve been thinking for much of this week about a recent essay in Strange Horizons, ‘Weight of History’ by Renay, in which she grapples with the question of what it is that makes a science fiction fan and, more precisely, what is it that a fan should have to know about science fiction. Is there such a thing as ‘the science fiction canon’ and if there is, who gets to say what’s in it? How much of it, if any, do you need to be familiar with before you can legitimately call yourself a fan of SF?

I’ve been enjoying Renay’s posts ever since she became a regular columnist at Strange Horizons and together with Shaun Duke she’s just finished putting together a particularly imaginative table of contents for Speculative Fiction 2014, an overview of online SFF criticism. I love the way Renay writes, the passion and open-mindedness of her approach. She is articulate, thoughtful and inclusive, and this essay in particular moved me because although I have a keen interest in science fiction history I often find myself dismayed by the attitudes on display in some of the more, shall we say entrenched segments of fandom, attitudes which seem to be more about a preening display of knowledge (in the manner of a peacock displaying its tail feathers) than the enthusiastic sharing and communication of love for science fiction literature. “How you’re introduced to something matters a lot,” writes Renay, “and if your introduction is a list of decades’ worth of writing and history that you’re subtly shamed for not knowing, that’s going to leave a mark.” Of course it is. A large part of the reason I’m writing this now is because of the frustration and anger I feel, that anyone should be made to feel they don’t know enough of the (frequently excruciating) backlist to be able to make a valid or useful contribution to the conversation.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Renay’s essay is the feeling she describes as the ‘cultural pressure to read stories by men’:

It’s hard to really feel dedicated to a communal storytelling space when the history of it is so steeped in one perspective that people outside the genre only see what floats to the top—those classics by men that everyone knows and that a quick google will help you find. And so that very limited vision is regurgitated over and over, pressing at you, reminding you there’s a history you don’t know and that not knowing it might be considered a failing.

So what exactly is going on here? Are the issues of historicity and sexism distinct, or are they inextricably a part of the same problem? I think it’s worthwhile to note here that SF is by no means alone in having this kind of baggage. In the exalted realm of mainstream literary fiction, ‘the canon’ is if anything even more restrictive, the power bases and cabals even more entrenched and aggressively protective of territory. From this we might infer that the canon as it currently operates within the field of science fiction is an almost entirely artificial construct, its main purpose to act as a kind of barrier to more progressive or divergent opinion: you don’t like our canon, we don’t want you in our discussion, end of.

At the same time, nothing exists in a vacuum and history happened. We need to study history, to an extent, to come to a proper understanding of the present. Is it not particularly important that we make ourselves aware of the least savoury aspects of that history in order for it not to be perpetuated?

At the same time, nothing exists in a vacuum and history happened. We need to study history, to an extent, to come to a proper understanding of the present. Is it not particularly important that we make ourselves aware of the least savoury aspects of that history in order for it not to be perpetuated?

All interesting questions, and questions that got me thinking about my own experience as a science fiction reader. How did I first come to the genre, and what did I find there? What do I think of the canon, then and now?

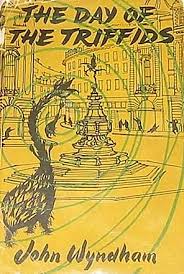

I was an obsessive reader from a young age but I honestly cannot say what first brought me to science fiction. My mum reads a lot, and quite widely, but to this day she has no interest in science fiction in any medium (she likes my stuff, by and large, but is still less than comfortable with any of its more overt horror or fantasy elements). My dad prefers spy stories and thrillers. So aside from a couple of Penguin edition John Wyndham novels (which needless to say I devoured avidly as soon as I was old enough to read them) there was no science fiction or fantasy on the shelves in our house.

Perhaps these things are hardwired into our DNA somehow, because I imprinted on Doctor Who from the first episode I saw (at the age of six) and by the time I was old enough to go to the library by myself I was heading straight for the science fiction section, a habit that continued pretty much until I went to university.

The SF section in our local library consisted almost entirely of the now- famous Gollancz ‘yellowjackets’ – very useful for anyone new to the genre because the books were so instantly recognisable. I used to browse the section happily for hours, eagerly looking for titles I’d not seen yet and knowing in advance that I’d be taking away stories crammed with all the stuff I was most into: weirdness, aliens, space travel, time travel, defiant rebels and renegade scientists, governments gone bad, deadly plagues, ideas and images and landscapes that were new to me and yet already so much ‘my thing’.

famous Gollancz ‘yellowjackets’ – very useful for anyone new to the genre because the books were so instantly recognisable. I used to browse the section happily for hours, eagerly looking for titles I’d not seen yet and knowing in advance that I’d be taking away stories crammed with all the stuff I was most into: weirdness, aliens, space travel, time travel, defiant rebels and renegade scientists, governments gone bad, deadly plagues, ideas and images and landscapes that were new to me and yet already so much ‘my thing’.

I read a lot of Golden Age science fiction, back in the day. I know I read quite a bit of Heinlein, shedloads of Asimov, Frederick Pohl was a particular favourite. I read Dune, I adored the ironical tone of Bob Shaw and Ian Watson – I read everything by Ian Watson I could get my hands on, although at the time I didn’t know he was British, I just presumed he and Shaw were American, like all the others. I loved anything dystopian or post-apoc – there was no bespoke YA back then, so after I’d read Brave New World and 1984 a couple of times I dug around and found bizarre and now totally forgotten books like Arthur Herzog’s Heat and IQ83 (‘Beans, beans, good for your heart…’) and Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day. I had an inexplicable fondness for a novel by Edmund Cooper called The Tenth Planet, which I read at least five times. There was nothing systematic about my reading. I had no idea really that there was a semi-cohesive genre called science fiction that people were fans of or had conversations about, much less argued and started decades-long feuds over. What did I know? I just loved reading it.

You may have noticed that none of the above titles are by women. Did I avoid SF by women? Did I not like SF by women? Nope. There just wasn’t any on the shelves for me to read. At some point during my early teens I came across Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea books and discovered a sense of wonder and identification that felt quite different from anything I’d found in any of the other, male-dominated science fiction I’d been reading. But I did not identify Le Guin with the Gollancz yellowjackets, and I had no idea she’d written other novels. The experience of reading Earthsea felt very private, a one-off. I did not explore further because I did not know how. (It’s sometimes difficult to remember how much harder it was before the internet, especially for young people, to zone in on the information they needed. Mostly you’d rely on teachers, or what was on the library shelves – if it wasn’t there it didn’t exist.)

I did not notice the lack of science fiction novels by women. Questions like this were never discussed, least of all in school. It didn’t bother me. I was too busy reading. I was certainly aware that many of the female characters in the science fiction I was reading did not appeal to me but I didn’t let that bother me overmuch either – I found sympathetic favourites among the male protagonists instead.

This is exactly how cycles of patriarchal reinforcement work, of course. But I didn’t know that then.

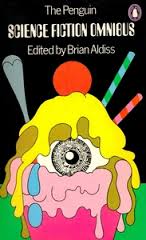

I suppose the first time I started to become aware of science fiction as ‘different’ from other literature, a literature that not everyone automatically liked or understood came when my ‘O’ Level English class was assigned The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus as one of our set texts (we had an amazing teacher, Jean Stupple, who was studying for her MA at the time and was passionate about literature in all its aspects – I owe my whole approach to twentieth century poetry to her), I was rubbing my hands in glee – I couldn’t wait to get stuck into that great big book of science fiction stories – and felt completely bemused when, as it turned out, pretty much half the class didn’t like what they read. Some people felt the stories weren’t ‘serious’ or that they were ‘weird’. Others clearly felt confused about how they should begin to write about them. Quite a few of my classmates opted out of the book and chose another text instead.

I suppose the first time I started to become aware of science fiction as ‘different’ from other literature, a literature that not everyone automatically liked or understood came when my ‘O’ Level English class was assigned The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus as one of our set texts (we had an amazing teacher, Jean Stupple, who was studying for her MA at the time and was passionate about literature in all its aspects – I owe my whole approach to twentieth century poetry to her), I was rubbing my hands in glee – I couldn’t wait to get stuck into that great big book of science fiction stories – and felt completely bemused when, as it turned out, pretty much half the class didn’t like what they read. Some people felt the stories weren’t ‘serious’ or that they were ‘weird’. Others clearly felt confused about how they should begin to write about them. Quite a few of my classmates opted out of the book and chose another text instead.

I retain a huge fondness for the Penguin Omnibus because it was such a big deal to me at the time. There are stories in it I still remember as being rather good (‘Lot’ by Ward Moore, ‘The End of Summer’ by Algis Budrys, ‘The Tunnel Under the World’ by Frederik Pohl, ‘The Country of the Kind’ by Damon Knight) and other curiosities that I’ll always remember because I read them here first (‘Grandpa’ by James H. Schmitz, ‘The Greater Thing’ by Tom Godwin, ‘Skirmish’ by Clifford Simak). But here’s the thing: looking again at that table of contents this week, I find it utterly heartbreaking to see and to realise, thirty years after I first encountered the book, that out of the thirty-six stories presented, only one (‘The Snowball Effect’ by Katherine MacLean) is by a woman.

The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus was assembled from the three Penguin science fiction anthologies edited by Brian Aldiss in the early 1960s and containing stories written over a roughly twenty-year period between 1941 and 1962. It was compiled under the guiding principle of presenting an overview of where science fiction was at, what had been achieved, who was writing the most interesting and original and intelligent work. A book to demonstrate to the uninitiated reader, maybe, why they should consider reading science fiction. Clearly for Aldiss at that time, the most intelligent, original and interesting science fiction was being written almost exclusively by men. Clearly it did not matter to him in the least that his ‘comprehensive’ omnibus excluded women writers. I’d be tempted to say it almost looks like a point of principle, the imbalance is so stark, only I don’t believe that’s the case. I think it is more likely that the imbalance happened because Aldiss simply did not notice it, or consider it to be important.

This too is heartbreaking to me. Seeing women’s writing, women’s contribution to science fiction erased in this way – that it is erased unintentionally almost makes it worse – makes me feel furious, and tired, and sad all at once. What we have in the Penguin Omnibus, I see now, is ‘the canon’ writ large, the closed circle being perpetuated, ever onward. Given the writers from that time period Aldiss could have included – C.L. Moore, L. Taylor Hansen, Carol Emshwiller, Kit Reed, Zenna Henderson, Leigh Brackett, Kate Wilhelm, Andre Norton, Naomi Mitchison to name but a handful – had he been bothered or so inclined to seek them out, makes this all the more galling. The inclusion of writers like these would have shifted the tone and emphasis of the anthology substantially towards a more fully formed, multi-faceted vision of the genre, perhaps attracting more readers, more women readers even towards SF. Maybe some of these women, seeing themselves reflected in the table of contents, might even – shock, horror! – have thought about writing some science fiction themselves…

The tired, establishment rejoinder to such observations is that we shouldn’t let issues of gender affect our choice of the best stories. The obvious flaw in that argument is how do we know we’re getting anything like the best stories, if the criteria for selection are pre-set and those who are doing the selecting either refuse or can’t be arsed to look beyond them? I think one of the biggest problems for people unfamiliar with or uneasy about the rhetoric surrounding questions of industry or cultural bias occurs at a level of basic misunderstanding. ‘Where are the active impediments to women writing, submitting, publishing?’ they ask. ‘Where are the editors and commentators and critics deviously working to keep women out of science fiction?’ In the majority of cases, of course, such active impediments and devious editors do not exist, or at least have not existed for some time. No one is arguing that they do. That does not mean that there is not a problem. The problem is systemic, a system of passive reinforcement of the status quo that is so long and deeply established that for large numbers of people – both men and women – living inside it, it is invisible. You only have to look at this sample list of ‘The Top 100 Science Fiction and Fantasy Books’ to see how effectively the same-old same-old continues to be given the nod at a grassroots level. Unlike the Penguin Omnibus from the 1960s, this selection was compiled just five years ago. Of the hundred books listed, only twelve women writers. Surely even those who insist there isn’t a problem can see that’s pathetic? That is far from the only list with a similar imbalance, either – just Google and see. Some of them are even worse.

So, getting back to Renay’s original conundrum: is there a continuing cultural pressure to read stories by men, and if there is, what should we do about it?

I think we’ve established that the answer to the first part of the question is yes there is, if only because the vast majority of so-called canonical science fiction that is presented for us to read – in anthologies, in SF Masterworks series, in best-of lists – is by men. As readers we naturally gravitate towards what is readily available, the names made familiar by repetition, the books people keep insisting that we need to read. In an area where we might feel a bit at sea and especially in need of guidance – Golden Age science fiction, for example – that effect will be doubled. Which is exactly how the system perpetuates itself.

As for what to do, there are various approaches. One of the comments on Renay’s post, from Tansy Rayner Roberts, provides both a superb analysis of the problem and a brilliant solution:

The thing is, the terrible/wonderful truth, is that you can’t catch up. No one can. What you also can’t do is compete on “contextualised reading” because you can’t replicate the experiences that many older SF fans have in common. You can never go back and read Heinlein in the 1970’s or Asimov as a twelve year old (boy) if they didn’t do it already. Just like my elder daughter read Harry Potter differently to me, and my younger daughter will read it differently agains.

But this LITERAL IMPOSSIBILITY to have the same experience with someone else’s canon is quite freeing because you get to make your own history. Your own essential canon. And if you really want “proper context” well, that’s what history books are for.

I can highly recommend finding your own classics. For every “but have you read Heinlein” or “Asimov had a great female character,” you can holler back with “But have you read all of Joanna Russ? I would tackle Heinlein but I’m starting with Delaney. I TRUMP YOU OCTAVIA BUTLER.”

I absolutely love this idea of finding your own classics, of making your own canon, if you will. I have become so dissatisfied with the popular, male-biased consensus view of science fiction history that I’m more than ever inclined to spend extra time researching those lesser known but equally important works that tell a different story of what science fiction is about and where it came from. Or that alter our perspective on the story as it stands. Or that simply give us some other names to think about, for God’s sake. (I’m not massive on Golden Age SF in any case but I’m particularly interested in what started happening with women and science fiction in the 1970s – see Jeanne Gomoll.)

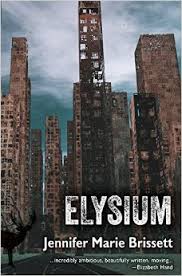

As we each find our own classics, so we all make our own science fiction. How great is that? If someone – a new reader or writer – were to ask me whether they needed to read the canon to be taken seriously I’d say absolutely not (and go tell the person who told you otherwise to STFU). The truth is that all the tropes of Golden Age SF will be familiar to you already – from games, from movies, from the cultural air that you breathe without even thinking about it. In a very real sense, you won’t be missing anything, and so if you can’t stomach the thought of wading through Heinlein or Herbert then don’t. You’d be far better off expending your time in reading science fiction that does inspire your interest, that speaks to you now and is relevant to the genre as it is evolving. Anyone who tells you you need to have read Arthur C. Clarke before you can form an opinion on Jennifer Marie Brissett is just plain wrong. (Those people won’t be reading Brissett anyway, they’ll be too busy getting stuck into David Brin or Greg Bear, ha ha.) In a very real sense, life is too short.

On the other hand, if you are genuinely interested in investigating how we got here from there, then there should be nothing to stop you sampling some of the Golden Age canon, even if simply out of morbid curiosity. Personally I find aspects of the canon fascinating. Very little of it is great literature – I frequently find myself dipping into something I might have read thirty years ago, only to give up in despair after a chapter or two, wondering what on Earth I used to see in this stuff first time round. I think I’d be right in saying that the only works that have made it into my personal canon from those early Gollancz yellowjacket days are the Strugatskys’ Roadside Picnic and Keith Roberts’s Pavane, both of which I’ve read at least three times since and so can confirm they hold up magnificently. But I love the SF conversation, the SF argument. I like knowing what’s in the canon so I can mess with it a bit. If anyone asked me where would be a good place to start with old school science fiction, I’d say they could do worse than to take a look at The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus. It’s a fascinating overview, both because and in spite of the fact that it’s so flawed. Also, short stories are going to take much less of your time than novels. You can learn a lot by reading anthologies, from any period. Much more fun than slogging your way through The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. (In fact in this case I’d say just…don’t.)

As for my own science fiction, what does that look like? I think I can safely say that my time with Heinlein and Asimov is over now, although I will probably have a go at rereading Clarke at some point. In spite of their faults, I am always going to love and cherish the works of John Wyndham because they’re a part of who I am as a reader and as a writer (Wyndham made a real effort with his female characters too, which I like to think isn’t a coincidence). I tend to think of the eighties and nineties as a bit of a dead time for me in SF, although I continue to be very interested in especially the British science fiction of the 1970s (not Moorcock, who is overrated in my opinion, but people like Compton, Coney, Cowper, Holdstock, Bailey, Saxton). Ballard, especially the early novels and his genius-level oeuvre of short fiction, is a cornerstone of my belief. I want to read a lot more of Joanna Russ, Marge Piercy and Thomas Disch. I’ve not yet read Octavia Butler and I need to remedy that. I would like to read all of Delany because I think he’s one of the most brilliant and original writers science fiction has ever produced. I continue to feel frustrated by a lot of contemporary genre SF, excited by the ideas that thrum through them yet disappointed by the rushed or stodgy or merely adequate quality of the writing itself. I hang around on the margins of genre, ceaselessly searching for those precious works which excite and innovate at a science fictional level and make you want to pump the air at their literary quality. That’s my science fiction and I love it.

As for my own science fiction, what does that look like? I think I can safely say that my time with Heinlein and Asimov is over now, although I will probably have a go at rereading Clarke at some point. In spite of their faults, I am always going to love and cherish the works of John Wyndham because they’re a part of who I am as a reader and as a writer (Wyndham made a real effort with his female characters too, which I like to think isn’t a coincidence). I tend to think of the eighties and nineties as a bit of a dead time for me in SF, although I continue to be very interested in especially the British science fiction of the 1970s (not Moorcock, who is overrated in my opinion, but people like Compton, Coney, Cowper, Holdstock, Bailey, Saxton). Ballard, especially the early novels and his genius-level oeuvre of short fiction, is a cornerstone of my belief. I want to read a lot more of Joanna Russ, Marge Piercy and Thomas Disch. I’ve not yet read Octavia Butler and I need to remedy that. I would like to read all of Delany because I think he’s one of the most brilliant and original writers science fiction has ever produced. I continue to feel frustrated by a lot of contemporary genre SF, excited by the ideas that thrum through them yet disappointed by the rushed or stodgy or merely adequate quality of the writing itself. I hang around on the margins of genre, ceaselessly searching for those precious works which excite and innovate at a science fictional level and make you want to pump the air at their literary quality. That’s my science fiction and I love it.

What I also love more than I can say is the way the genre is beginning to diversify. The proliferation of fin-de-siecle essays about the exhaustion of science fiction were, to my mind, a reflection of the state of a genre that had been drawing from the same well for way too long – that is, the canon, the same old, the pulps, the Gernsbackian tradition. What science fiction desperately needed was a transfusion of new blood, not just younger writers but different writers, writers drawing on influences, traditions and experiences that were not necessarily centred upon Heinlein and Silverberg and the American SF writing of the 1950s. Happily, that transfusion is now beginning to take place.

If I’m drawing my influence from anywhere now I would like it to be from the sincerity and conviction of some of these new writers, writers whose ability to imagine and communicate often leaves what we are doing in western science fiction looking stale and flabby and tired. I want to read books that feel as if they mattered to the writer, urgently. I am finding this quality, more and more often, in novels by writers who come from way outside the canon but who will, and thank God for that, inject new life into it. I think Nnedi Okorafor is writing some of the most interesting stuff around now and her linguistic and stylistic palette is just stunning. Sofia Samatar’s A Stranger in Olondria was one of the most accomplished debuts in recent memory and everything she writes is not only resplendent in its linguistic prowess but above all it feels meant. There’s a novel just recently come out by Saad Hossain called Escape from Baghdad! and it’s so bitingly funny, so original and so necessary I’d urge anyone and everyone to read it, science fiction fan or no. Especially in the field of short fiction, we are seeing a huge upsurge of work appearing from writers whose backgrounds and influences lie outside of the western mainstream, writers like Usman Malik who was recently nominated for a Nebula, writers like Kai Ashante Wilson and Alyssa Wong who have just been shortlisted for the World Fantasy Award, writers like Vandana Singh whose work would seem to be one of the perfect fusions of science and fiction out there at the moment, writers like Zen Cho, whose story collection Spirits Abroad is so original and so accomplished I was disappointed not to see it appearing on some of the mainstream literary prize shortlists. Of the short fiction I read last year, ‘Autodidact’ by Benjanun Sriduangkaew lingers in my memory for its intensity of feeling and outstanding technical accomplishment. JY Yang’s ‘Storytelling for the Night Clerk’ has also stayed with me as the work of a powerful new voice with no fear of innovation. One of my favourite stories of this year so far, ‘Documentary’ by Vajra Chandrasekera, comes from a writer whose blog essays on science fiction and some of the issues surrounding it are also of a most superior quality – more, Vajra, please!

sincerity and conviction of some of these new writers, writers whose ability to imagine and communicate often leaves what we are doing in western science fiction looking stale and flabby and tired. I want to read books that feel as if they mattered to the writer, urgently. I am finding this quality, more and more often, in novels by writers who come from way outside the canon but who will, and thank God for that, inject new life into it. I think Nnedi Okorafor is writing some of the most interesting stuff around now and her linguistic and stylistic palette is just stunning. Sofia Samatar’s A Stranger in Olondria was one of the most accomplished debuts in recent memory and everything she writes is not only resplendent in its linguistic prowess but above all it feels meant. There’s a novel just recently come out by Saad Hossain called Escape from Baghdad! and it’s so bitingly funny, so original and so necessary I’d urge anyone and everyone to read it, science fiction fan or no. Especially in the field of short fiction, we are seeing a huge upsurge of work appearing from writers whose backgrounds and influences lie outside of the western mainstream, writers like Usman Malik who was recently nominated for a Nebula, writers like Kai Ashante Wilson and Alyssa Wong who have just been shortlisted for the World Fantasy Award, writers like Vandana Singh whose work would seem to be one of the perfect fusions of science and fiction out there at the moment, writers like Zen Cho, whose story collection Spirits Abroad is so original and so accomplished I was disappointed not to see it appearing on some of the mainstream literary prize shortlists. Of the short fiction I read last year, ‘Autodidact’ by Benjanun Sriduangkaew lingers in my memory for its intensity of feeling and outstanding technical accomplishment. JY Yang’s ‘Storytelling for the Night Clerk’ has also stayed with me as the work of a powerful new voice with no fear of innovation. One of my favourite stories of this year so far, ‘Documentary’ by Vajra Chandrasekera, comes from a writer whose blog essays on science fiction and some of the issues surrounding it are also of a most superior quality – more, Vajra, please!

I hope we’ll be seeing novels from all these writers in due course – indeed Zen Cho already has one forthcoming. These writers and others like them are not just challenging the canon as it stands, they are beginning to reform it. They are making science fiction an exciting, innovative place to be again. As discussions of the Golden Age canon make little sense now without reference to the New Wave that challenged the old order and polarised opinion within it, so our discussions of ‘whither SF’ and the wearing out of genre materials make no sense at all if we don’t talk about what is happening in science fiction right now to reverse those predictions. A static canon is a dead canon. Fossils that are allowed to stay on the shelf simply because they’ve always been there are just that: fossils. We don’t have to throw them all out, necessarily, but surely we should re-examine them in the light of our thoughts, preferences and ambitions as they stand today, rather than leaving our evaluations under the sole control of memory, which is so often fickle, or tradition, which is so often stagnatory?

I hope we’ll be seeing novels from all these writers in due course – indeed Zen Cho already has one forthcoming. These writers and others like them are not just challenging the canon as it stands, they are beginning to reform it. They are making science fiction an exciting, innovative place to be again. As discussions of the Golden Age canon make little sense now without reference to the New Wave that challenged the old order and polarised opinion within it, so our discussions of ‘whither SF’ and the wearing out of genre materials make no sense at all if we don’t talk about what is happening in science fiction right now to reverse those predictions. A static canon is a dead canon. Fossils that are allowed to stay on the shelf simply because they’ve always been there are just that: fossils. We don’t have to throw them all out, necessarily, but surely we should re-examine them in the light of our thoughts, preferences and ambitions as they stand today, rather than leaving our evaluations under the sole control of memory, which is so often fickle, or tradition, which is so often stagnatory?

Science fiction is still the most radical literature alive. Radical means sticking two fingers up at the canon at least once a day. Don’t let anyone tell you what your experience of science fiction should be. This is something you should be deciding for yourself.

It still amazes me, how critics still seem not to ‘get’ Joyce Carol Oates, how often her prodigious talent is spoken of dismissively, in belittling terms – ‘oh, Joyce Carol Oates, there’s just so much of it!’ – as if her very prodigiousness, the prolific expression of her talent could be a reason to reject it as something freakish and therefore unworthy in some way.

It still amazes me, how critics still seem not to ‘get’ Joyce Carol Oates, how often her prodigious talent is spoken of dismissively, in belittling terms – ‘oh, Joyce Carol Oates, there’s just so much of it!’ – as if her very prodigiousness, the prolific expression of her talent could be a reason to reject it as something freakish and therefore unworthy in some way.