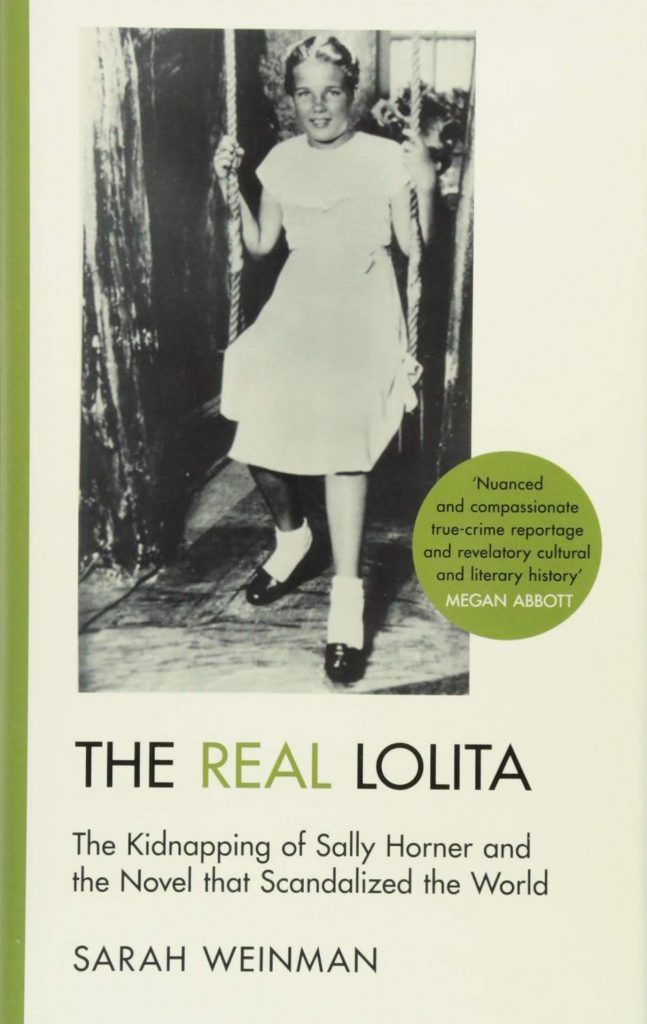

The Real Lolita by Sarah Weinman (2018)

Over and over, scholars and biographers have searched for direct connections between Nabokov and young children, and failed to find them. What impulses he possessed were literary, not literal, in the manner of the ‘well adjusted’ writer who persists in writing about the worst sort of crimes. We generally don’t hear the same suspicions of writers who turn serial killers into folk heroes. No one, for example, thinks Thomas Harris capable of the terrible deeds of Hannibal Lecter, even though he invested them with chilling psychological insight.

Sarah Weinman is a writer I admire. Both in her promotion of underappreciated women crime writers, and in her own field of true crime journalism and longform essay writing, she is one of the best of the new generation currently working. Her skill in creating compelling narratives, diligent research and all-round passion for the genre, together with her ability to ask tough questions, her fascinating insights into social issues and the history of criminology all serve to make her work an essential reference point and, most of all, a joy to read. When I learned she’d written a book centred around the Sally Horner case and its relationship to Nabokov’s Lolita, it went straight on my to-read list. Two of my key literary interests, brought together by one of my favourite writers? I fully expected The Real Lolita to be one of my books of the year.

As it turned out, this was not the case. I ended up not liking this book, in the main because I passionately disagree with the thrust of Weinman’s argument. I could go further and say I don’t think Weinman understands Nabokov, or the process of fiction-writing. Even as a work of true crime literature, The Real Lolita has significant problems, and at least some of my issue with this book lies in its being not just unsubstantiated, but insubstantial. Weinman’s writing is as well researched and readable as ever, and I am sure there will be plenty who will not only enjoy The Real Lolita a great deal more than I did, but who will be more sympathetic to Weinman in the arguments she makes. That’s a good thing – Weinman is always worth reading, and one could argue that these kind of judgements are subjective – but for anyone interested in Nabokov in particular I would caution them to approach with a degree of scepticism. (And please, please, please read this instead!)

The Real Lolita started life in 2014, as an essay in Hazlitt, and arguably this is where it should have stayed. The background details of Sally Horner’s kidnapping and how the case might have influenced Nabokov in the way he eventually chose to structure Lolita make for a fascinating essay, pointing up one of the many instances in which novelists have always been influenced and inspired by real-life cases. I can even see why Weinman was tempted to expand the essay into a book. But I don’t think there is enough material here to justify that decision.

In the March of 1948, ten-year-old Florence ‘Sally’ Horner was dared by her schoolfriends to perform a minor act of theft from a Woolworth’s store in her hometown of Camden, New Jersey. As Sally tried to make her escape, she was confronted by a man claiming to be an FBI officer, who cautioned Sally that he had seen what she did, and that he’d be keeping her under his watch in the months to come. Understandably, Sally was terrified and told no one about the encounter. Three months later the man – not an FBI agent but a motor mechanic named Frank La Salle – returned to claim Sally, persuading her mother that he was the father of one of Sally’s schoolfriends, that he was taking them on holiday to Atlantic City and that Sally herself was desperate to come along for the ride. What for Sally began as a desperately unlucky chance encounter went on to become a twenty-one-month ordeal. After kidnapping Sally from her hometown, Frank La Salle drove her across the United States, subjecting her to multiple rapes and a campaign of coercive control in which he threatened that she would be sent to reform school if she told anyone what was happening or tried to escape.

Eventually, Sally was brave enough to confide in a neighbour, who encouraged her to call the police immediately. Sally then made contact with her sister and brother-in-law back in New Jersey, who raised the alarm. Sally was rescued by federal agents the same day. Frank La Salle, after being extradited to New Jersey to face charges, was sentenced to thirty-five years in jail. Astonishingly, he persisted in his fantasy that he was Sally’s real father.

As always, Weinman is excellent not only in recounting the facts, but in setting the scene, grounding her investigation vividly in place and time. She draws us into the story immediately, laying out the string of weird coincidences, systemic failures and blind, unlucky chance that enabled La Salle’s exploits – and Sally’s ordeal – to continue for so long. Riveting though Weinman’s account is, I still found myself unsettled by some of the assumptions she seemed to be making. For most of the time she was in captivity, Sally was leading what looked on the surface to be a normal life – La Salle always enrolled Sally in school wherever they happened to be, for example, for whatever reason seeming to prefer Catholic institutions. Perhaps, ironically, he liked the idea of Sally being in a more morally rigorous, less laissez-faire environment. Weinman takes a different view:

But I suspect La Salle gravitated toward Catholic institutions because they were a good place to hide in plain sight. The Church, as we now know from decades’ worth of scandal, hid generations of abused victims, and moved pedophile priests from parish to parish because covering up their crimes protected the Church’s carefully crafted image. Perhaps La Salle saw parochial schools for what they were: a place for complicity and enabling to flourish. A place where no one would ask Sally Horner if something terrible was happening to her.

This is tendentious at best, full of harmful assumptions at worst, not least because the various scandals around paedophile priests were still decades from being uncovered, or openly discussed. I also find it disappointing that Weinman chooses not to comment on the less than humane treatment Sally was subjected to by law enforcement after her rescue. In spite of her repeated and totally understandable insistence that all she wanted was to be allowed to go home, Sally Horner was remanded in police custody in a juvenile detention facility for the duration of legal proceedings. The reasoning behind this was supposedly ‘to ensure the girl stayed in a calm frame of mind before and during the trial’. Only her mother is allowed to visit her, at the state’s discretion. Considering that Sally has done absolutely nothing to warrant such a summary revocation of her freedom, moreover, that she has just endured twenty-one-months being held against her will by a known paedophile, this stipulation seems not only authoritarian, but barbaric.

Of course, the attitude to minors as people with rights has evolved considerably since then, but in 1950s America summarily stripping children and parents of their autonomy was accepted practice, not just in reform schools but in hospitals, mental welfare facilities and the educational system. The situation in the UK was no different. I would have liked to have seen Weinman delve into this more, but she leaves the problematic behaviour of the police and courts unexamined, commenting only that ‘thanks to an unexpected development, Sally’s stay at the center didn’t last long at all.’ Given that Sally escaped at the end of March 1950, and prosecuting attorney Mitchell Cohen ‘expected the case to go before the jury no earlier than June’, La Salle’s prompt decision to plead guilty was fortunate indeed. It seems odd to me that Weinman does not express greater outrage, almost as if she is concerned that any such criticism of those who are ostensibly ‘the good guys’ would be bad form.

This seeming reluctance to criticise the US judicial system does not end there:

The extensive media coverage meant all of Camden, and much of Philadelphia and the surrounding towns, knew what had happened to Sally. Cohen worried the girl might be judged harshly for the forcible loss of her virtue, even if that reaction was in no way warranted. Cohen also urged [Sally’s mother] to seek the advice of the Reverend Alfred Jass, director of the Bureau of Catholic Charities, ‘in directing Sally’s return to a normal life’. Ella was a Protestant, but clergy was still clergy, and Sally’s recent attendance at Catholic schools may have influenced Cohen’s choice of religious adviser.

Given Weinman’s earlier portrayal of Catholic schools as hotbeds of paedophilia, to let this pass without comment seems extraordinary to me. The treatment of Sally and her mother following her rescue displays many of the hallmarks of sexism and classism still rampant in the American justice system today, a fact that surely warrants more attention than it is given here. It would also have been interesting to look at Cohen’s advice to Ella about changing her place of domicile, even her identity, following Sally’s release – advice that, to my mind, was both patronising and utterly clueless about Ella’s family and financial circumstances – in the light of the toxic media climate around more recent abduction cases, that of Madeleine McCann in the UK, for example, which has seen the missing girl’s parents demonised and gaslighted over a period of more than a decade. Real-life parallels like these might ultimately have been a more interesting and fruitful investigation to follow than the small and ultimately peripheral connection between Sally Horner;s abduction and Nabokov’s novel Lolita.

Weinman does a better job of picking apart the aftermath of Sally’s ordeal: the bullying she experiences from classmates (‘No matter how you looked at it, she was a slut’ Carol said. ‘That’s the way it was in those days.’), as well as the blanket erasure of the episode from family history. She is also excellent on the city of Camden and the changes wrought by post-war social upheavals. Her account of the cases prosecuted by Mitchell Cohen is insightful and informed, in particular the 1949 spree killing perpetrated by army veteran and gun obsessive Howard Unruh. It is ironic though, given the subject of her book, that she does not bring attention to the hideous appropriateness of this mass-murderer’s surname. Nabokov, with his ability to move fluidly between several European languages, certainly would have done.

And it is in the territory of Nabokov’s fiction that Weinman seems least comfortable. Her contention, broadly, is that it was reading about the case of Sally Horner that finally freed up the mental logjam Nabokov had been experiencing in the writing of what turned out to be his most famous novel. Indeed, she goes further:

Sally Horner’s story mattered to Nabokov because Lolita would not have been finished if he hadn’t read of Sally’s kidnapping.

That is a vast assumption, by any stretch, all the more so when we consider the paucity of evidence Weinman is able to cite in bringing her case. Anyone with more than a passing knowledge of Nabokov’s work will be aware that he had been grappling with the themes and obsessions that govern the narrative of Lolita long before he came to America and before Sally Horner was born. The pursuit of young girls by predatory older men forms the subject of several of Nabokov’s early short stories, and is fleshed out at greater length in his novella of 1939, The Enchanter, which also happens to be the last work he wrote in Russian. Weinman is at pains to stress the supposed inferiority of this earlier work, which, she suggests, was written before he possessed the literary wherewithal to adequately exploit his chosen theme:

Nabokov was not quite the artist he would later become, and it shows in the prose: ‘I’m not attracted to every schoolgirl that comes along, far from it – how many one sees, on a grey morning street, that are husky, or skinny, or have a necklace of pimples or wear spectacles – these kinds interest me as little, in the amorous sense, as a lumpy female acquaintance might interest someone else.’ He doesn’t have the wherewithal to describe his chosen prey, whom he first sees roller-skating in a park, as a nymphet. Such a word isn’t in his vocabulary because it wasn’t yet in Nabokov’s.

Weinman then goes on to compare this passage with a passage in Lolita whilst failing to acknowledge that the former is a translation from the original Russian by Nabokov’s son Dmitri, whilst the latter consists of words and sentences actually written by Nabokov in English. This omission strikes me as strange, as does the assertion that Nabokov’s narrator in The Enchanter lacks the ‘wherewithal’ to describe his pre-pubescent victim as a nymphet – as if ‘nymphet’ were a previously existing descriptor, rather than a term Nabokov himself was responsible for introducing into the English language. Similarly:

The Enchanter’s narrator may be tormented by his unnatural tastes, but he knows he is about to entice his chosen girl to cross a chasm that cannot be uncrossed. Namely, she is innocent now, but she won’t be after he has his way with her. Humbert Humbert would never be so obvious. He has the ‘fancy prose style’ at his disposal to couch or deflect his intentions. So when he does state the obvious – as he will, again and again – the reader is essentially magicked into believing Dolores is as much the pursuer as the pursued.

I would take this as a serious misreading of Lolita, more importantly, a serious underestimation of how the book works and what it is about. Early on in The Real Lolita, Weiman reports the experiences of the writer Mikita Brottman, who discussed Lolita with male prisoners as part of a prison outreach program. While Brottman confessed that Humbert’s ability to dress up his crimes in erudite language meant that she had ‘immediately fallen in love with the narrator’, the prisoners in the book club were not so beguiled:

An hour into the discussion, one of them looked up at Brottman and cried, ‘He’s just an old pedo!’ A second prisoner added: ‘It’s all bullshit, all his long, fancy words. I can see through it. It’s all a cover-up. I know what he wants to do with her.’

Anyone arguing that Nabokov’s aim in Lolita is to dupe his readership might do well to consider this account of the novel’s impact on ordinary readers. We need also to keep it in mind that Humbert is a literary device, not a flesh-and-blood narrator, that part of Nabokov’s skill in Lolita lies in the way he constructs the novel so as to reveal the inadequacy of Humbert’s language in hiding his true nature.

I was regularly nonplussed by Weinman’s reading of specific parts of the text, for example in the way she describes the events leading up to Humbert’s duplicitous marriage to Lolita’s mother, Charlotte Haze :

Charlotte, bafflingly, concludes that if he showed no romantic interest in her and remained in her home, then she would take it that he was ‘ready to link up your life with mine forever and ever and be a father to my little girl.’ (Since we’re always in Humbert’s head, we have only his word that Charlotte wrote this.)

Well, up to a point, I guess, but the whole essence of Humbert lies in his devastating honesty. And at this point in the narrative, we’re not ‘in Humbert’s head’ in any case, as he includes the text of Charlotte’s letter in full. What it actually reads is:

If I found you at home (and I know I won’t – and that’s why I am able to go on like this) the fact of your remaining would mean only one thing: that you want me as much as I do you; as a lifelong mate; and that you are ready to link up your life with mine forever and ever and be a father to my little girl.

Nothing baffling about that, and I can’t explain why Weinman’s sense of this passage is so muddled that she misquotes it entirely. Throughout her analysis, she displays a curious tendency to write about Nabokov’s characters as if they were autonomous individuals, comparing their actions with those involved in the Sally Horner case as if they were active participants in an alternative true-crime scenario:

Dolores Haze’s husband, Dick Schiller, had to raise their child without her. But another woman had to reckon with the collateral damage of a father’s abuse. That woman was Frank La Salle’s daughter, known as Madeline.

Weinman indulges in this kind of dream logic not just once but many times, eventually coming to the conclusion that:

It is to Nabokov’s credit that something of the true character of Dolores – her messy, complicated, childish self – emerges out of the haze of his narrator’s perverse pedestal-placing.

That would be because the gap between Humbert’s view of himself and the wider reality forms one of the central tenets of the entire book. For me, slips like these are symptomatic of Weinman’s overarching failing here: that is, her insistence on addressing Lolita in terms of its morality, on reading Nabokov’s text so literally as a novel ‘about paedophilia.’ Throughout her analysis, she remains convinced that the seminal effect of Lolita upon most readers will be that of being tricked:

Lolita moved far beyond the bestseller list to become a cultural and global phenomenon. The template was in place for generations of readers to be taken in by Humbert Humbert, forgetting that Dolores Haze was his victim, not his seducer.

I first read Lolita at the age of seventeen. I had read nothing like it before, and I still remember the painful urgency I felt, to get the book over with as quickly as possible because I found its content so desperately upsetting. At the same time, I was thrilled in a way I had not experienced since first reading Eliot’s The Waste Land a couple of years earlier, to find myself confronted with a work of fiction that was so unquestionably a work of genius. I have read the novel three or four times since over the years, and its power as both narrative and text remains undiminished. I firmly believe that any attentive reader will be aware throughout of the hideous disjuncture between what Humbert says and what Humbert does, as well as Nabokov’s brilliance in having his narrator undermine himself with every word he speaks. One comes away from Lolita loathing Humbert, yet exhilarated by the experience of being in the hands of such an outrageously gifted storyteller – Nabokov, that is, and very much not, as Weinman keeps insisting, Humbert Humbert.

Weinman’s contentions around the genesis, publication and reception of Lolita are, for me, as tendentious and wide of the mark as her analysis of the text. The central premise of The Real Lolita is that Nabokov’s novel as we know it could not and would not have existed in the absence of Sally Horner’s own real-life suffering. Not only does this ‘fact’ needs to be addressed, Weinman argues, but Nabokov should also be posthumously held to account for his underhandedness in appropriating material that was not his to exploit. As a response to this, I can do no better than to repeat the words used by Vera Nabokov in reply to a letter sent to her husband by Alan Levin, a reporter at the New York Post. Having read of Nabokov’s purported interest in the Horner case, Levin was curious to know, in Weinman’s words, ‘if it could be true that Lolita owed its plot to a sensational kidnapping, and if it was true, what would the great Vladimir Nabokov have to say on the matter,’ Vera, who dealt with Nabokov’s correspondence as a matter of course, replied as follows:

At the time he was writing Lolita he studied a considerable number of case histories (‘real’ stories) many of which have more affinities with the Lolita plot… [The Horner case] is mentioned also in the book Lolita. It did not inspire the book. My husband wonders what importance could possibly be attached to the existence in ‘real’ life of ‘actual rape abductions’ when explaining the existence of an ‘invented’ book.

Weinman reacts to what is a straightforward and factually correct piece of correspondence in a way that suggests a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of fiction-writing:

How the Nabokovs handled Levin’s letter, and by extension Welding’s article for Nugget, is a window into their maddening, contradictory behaviour when anyone probed Lolita’s possible influences. They denied the importance of Sally Horner but acknowledged the parenthetical. They mentioned a ‘considerable number’ of case histories, but only Sally’s is described in the novel.

So what??

Vera’s stubborn insistence that the Sally Horner story ‘did not inspire the book’ is akin to trying to drown out a troublesome argument with the braying of one’s own voice. Though it worked, since Levin did not push back – at least, not that we know of.

And that would probably be because there was nothing to push back against. What Weinman suggests here is that it is or should be incumbent on the writer, to disclose their inspirations, describe their processes, quantify how much and how often they might have made mental or actual reference to realworld events and for what reason and on what authority and by whose leave. While other more recent shenanigans in the world of books (I’m sure we can all cite at least three from the past six months alone) might seem to indicate an increasing number of commentators (I will not call them critics) who believe exactly that, I say it’s bollocks. More than that, it’s dangerous bollocks, and should be named as such.

Any and all of the information about Sally Horner’s case to which Nabokov had access was firmly in the public domain, available to anyone who was interested to read and discuss. Had Nabokov nefariously obtained previously unknown, off-the-record information about Sally or her family, which he then proceeded to make public use of for his own fame or profit, the question of justification might be radically different. But as a writer I believe, and would argue strongly, that any such information obtained simply by reading it in a newspaper or seeing a report on TV does not present any boundary issues or moral questions in terms of its use as source material or inspiration. Both legally and morally speaking, there is no case for Nabokov to answer, especially as he famously makes direct reference to the case in his own text.

As it concerns the germination and narrative direction of Lolita, the story of Sally Horner for Nabokov was a lucky accident, the kind of ‘ah ha!’ moment of synchronicity any writer might experience in seeing their current area of interest echoed in a real-life incident. The itch to write Lolita was there long before Sally was kidnapped – Weinman herself has said as much. It is fascinating to read the notes Nabokov made about the case on one of his index cards, complete with summary observations and corrections. It is perplexing and vaguely annoying to see Weinman waste time speculating over why Nabokov did not burn these cards to hide his tracks. (That would be a) because there was nothing to hide and b) those index cards were an inalienable and lifelong part of his writing process and he counted them as part of the work itself.)

The simple and rather ordinary facts – that Nabokov probably did read about this infamous kidnapping case around the same time as he was re-engaging with the manuscript that would become Lolita – are presented by Weinman as some kind of revelation. As any novelist would tell you, they are nothing of the kind: Writers are magpies and writers are hoarders – we pick things up, save them for later to decorate our nests with. All fiction is an amalgam of lived experience and imaginative construct. It is a giant leap of logic to state, as Weinman does, that Sally’s story is so central to the genesis of Lolita that ‘it’s surprising to think the novel could have existed without it.’ The truth is, if the story of Sally Horner hadn’t happened along, something else would have.

If Nabokov had been a one-hit wonder, with Lolita as the sparkling solitaire diamond in an otherwise unremarkable oeuvre, then Weinman’s insistence on the importance of Sally’s story particularly might bear more examination, but this is very much not the case. Lolita might be Nabokov’s best-known book, but he wrote at least a half-dozen others that in terms of their literary brilliance are easily its equal. Sally’s story, and the telling of Sally’s story, is important in the real world – for surviving relatives, for other victims, for the interests of justice, most of all for the purposes of honouring Sally’s memory, and I can absolutely see the fascination in reading about the true-crime background of a novel as important and controversial as Lolita. But in the end we must conclude that in the context of Nabokov’s development as a writer, the significance of Sally’s story is marginal, background colour.