A week or so ago a friend sent me a link to a Booktube video by Jules Burt, a book dealer and vintage paperback collector with a wealth of bookish knowledge and a love of science fiction. This particular video shows Jules unboxing his then most recent purchase, a consignment of titles issued by the British Science Fiction Book Club, which ran on a monthly subscription from 1953 until 1971.

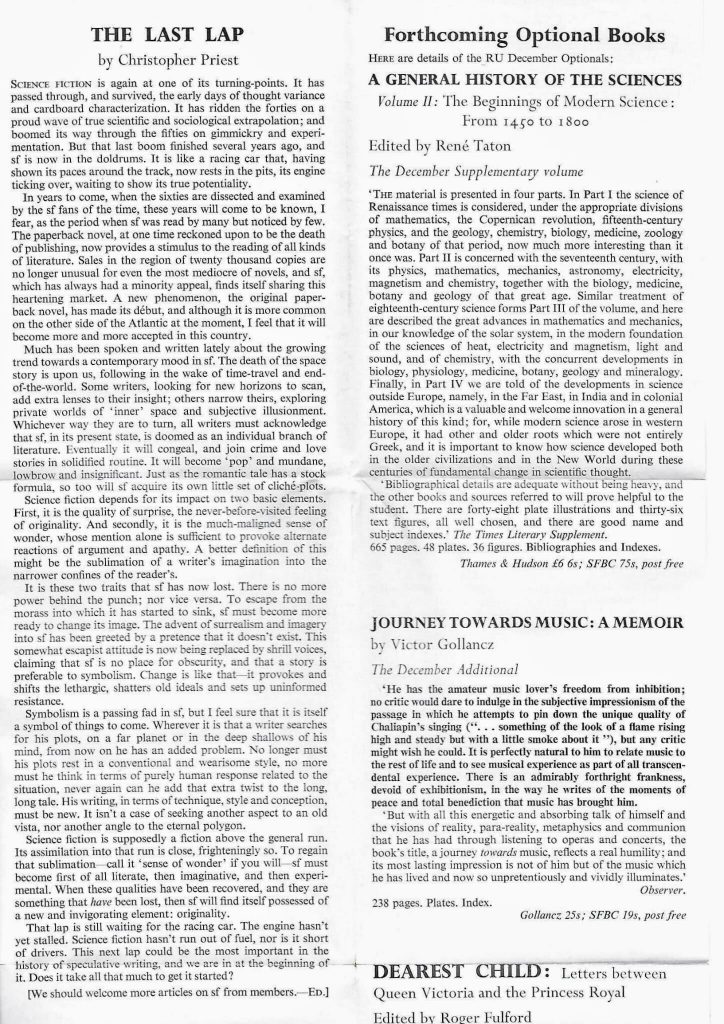

The monthly selections are interesting and actually quite progressive – the club kicked off with the now classic but then just four years published Earth Abides by George R. Stewart and went on to feature more future landmarks of science fiction literature by Ray Bradbury (The Martian Chronicles), Kurt Vonnegut (Player Piano), John Christopher (The Death of Grass) , Chip Delany (Nova), and John Wyndham (Trouble with Lichen) among many others. The books were all issued in hardcover and featured bold, modern cover designs, not unlike the Penguin science fiction covers of the same era. I like them a lot. But the reason my friend sent me the video was less for the books themselves than for a flyer insert that Jules had discovered inside one of them while he was unboxing it: the SF Book Club’s monthly newsletter, which just happened to include a mini-essay called ‘The Last Lap’, by a certain Christopher Priest.

Chris often spoke of the SF Book Club – he still owned the SFBC edition of JG Ballard’s The Drowned World, as well as several other titles – but he had never mentioned writing for the newsletter and I had no idea this essay existed. It was a delightful surprise, all the more so for being so quintessentially Chris.

‘The Last Lap’ was written in 1965. Chris was twenty-two years old, still a year out from making his first pro sale. (I was not even born.) But what is remarkable about the piece is how clearly it shows that even at this very early stage of his career, both the passion Chris had for science fiction and his insistence that those who wanted to write it be ambitious and demanding of their chosen material were already established.

‘Science fiction is supposedly a fiction above the general run,’ he writes. ‘Its assimilation into that run is close, frighteningly so. To regain that sublimation – call it “sense of wonder” if you will – SF must become first of all literate, then imaginative, and then experimental. When these qualities have been recovered, and they are something that have been lost, then SF will find itself possessed of a new and invigorating element: originality.’ Science fiction must in other words be technically well written, far-reaching in its scope and innovative in its manner of expression. I am tempted to say that if we had more twenty-two-year-olds in SF right now who felt equally moved to express such concerns we would have a better literature. But I think I’m done with carping, not only because those who carp inevitably end up preaching to the converted, but also because they run the risk of becoming wearyingly repetitive.

I find ‘The Last Lap’ incredibly moving, all the more so because for the sixty-year duration of the career that followed, Chris never gave up on the principles he outlined, nor lost interest in what they represented. Every novel and story he wrote strove to be original, exploratory, different from the one before it – it is this quality of intent that makes his oeuvre so consistent, so unified. The essay is fascinating in a broader sense, though, for what it says about us, and by us I mean those in science fiction with a love of polemic, of criticism, of argument. What is perhaps most notable about ‘The Last Lap’ is that – a scattering of date-specific minor details aside – it could have been written any time at all in the sixty years since. It could have been written last week. I would hazard a guess that it might equally have been written five or ten years earlier.

There have been some magnificent ‘SF is doomed’ polemics in recent years. Chris’s own ‘Hull 0: Scunthorpe 3’ from 2012 (fondly known as ‘Priestgate’) is one example, with another favourite being Paul Kincaid’s ‘The Widening Gyre’ in the LA Review of Books from the same year, in which Paul compares three of the annual ‘best of’ anthologies in an attempt to answer the perennial question: ‘Is SF exhausted?’, a question that – to those of us who are in deep with these matters at least – is becoming as over-familiar as ‘Is the novel dead?’

In ‘The Last Lap’, Chris points to symbolism in SF as ‘a passing fad’, just as ‘the death of the space story is upon us’. He fears that SF is ‘like a racing car that, having shown its paces around the track, now rests in the pits’. His essay is in this way similar to those that went before and many that came after – including a fair few of my own – that protest the condition of SF without being entirely sure of how, specifically, it should be remedied. In the end, what all these essays come down to is: SF should be less like [writer/s I don’t like] and more like [writer/s I do].

This is normal, natural, even healthy. I’ve enjoyed writing essays like that, mainly because they get me thinking, asking myself the same questions the essay is asking of others, and for this reason alone I would not be foolish enough to promise I’ll never write another. But the deeper conclusion that must be drawn is that nothing really changes: the state of play is always vexed, the industry is always toxic, and SF is always exhausted. The opposite is equally true. By the time he and I met, Chris had (almost!) given up on the idea of SF as a unified entity. ‘There’s no such thing as “the field”,’ he would say, ‘there are just individual books, by individual writers, many of which are bad, some of which are great.’ It was these individually great books and authors, he maintained, that we should read and pay attention to, that we should discuss with reference to themselves, and to literature as a whole, rather than subjecting them to an artificial analysis within the confines of a genre that had outlived – in terms of criticism at least – its usefulness.

How I feel about this argument varies – according to my energy levels, my state of mind, even the book I happen to have just read. But what is absolutely not in dispute is that there are and have always been superlative individual novels and writers of the fantastic, books that break boundaries and challenge norms even in the midst of the most conservative periods of genre complacency and orthodoxy. These are the books and writers that ultimately matter, that shape the literature going forward, even when, in the present moment, they appear to be outliers with zero chance of influencing anything, such is the quantity of identikit cosy fantasies and interchangeable space operas stacked against them.

I have spent the past year – the past two years, really – in the literary company of JG Ballard, a writer who, in his essays and reviews for New Worlds in the early 1960s, produced some of the greatest and most resilient ‘SF is exhausted’ polemics in the secondary literature. His novels, even when they contain no outwardly speculative elements, were from the first until the last written with what I like to describe as a science fictional sensibility: that is, through a lens of deeper imagining, through a habit of questioning and subverting the status quo. For Chris at the time he wrote ‘The Last Lap’, Ballard was a key inspiration, one of the outliers, the writers who showed by example some of the ways in which SF might reach its full potential. His decision to embark on a full-length study of Ballard’s life and work in the late autumn of 2022 was a kind of homecoming.

Working to complete that project has been a vital source of intellectual and emotional sustenance for me through the difficult, bewildering months of 2024, the only thing that made sense, firstly because it’s been so challenging and in the pursuit of writing at least that is what I thrive on, but mainly because it is the continuation of a conversation that will never end.

Keep asking the questions. Keep striving for better. Keep feeding the fire.

Per aspera ad astra. Happy New Year.