We’ve reached that time of year when everyone is posting their best-of-year lists. I feel a bit ambivalent about doing this in 2014, because although I’ve read plenty of interesting stuff, no one book seemed to proclaim itself ‘overall winner’ for me. So I thought I’d do something a bit different, and post a summary of all the SFF novels I’ve read over the past 12 months that will be eligible for awards in 2015. This should hopefully get me in the mood to start thinking about my nominations ballots. So in the order of reading:

1) Wolves by Simon Ings

I wrote a bit about Wolves here at my blog. I loved this novel. Even if I can see objectively that the plot is a bit woolly in parts (could a teenage boy really get an adult dead body into the boot of a car unaided and unobserved?) I didn’t honestly care, because the style and ambience of the novel, together with what it had to say about unsustainable development and the destructive power of future-consumerism for its own sake, resonated so deeply with me that I was won over more or less from page one. If Wolves doesn’t make it on to a shortlist or two, I’d be severely disappointed. And a shout-out to Jeffrey Alan Love for the cover also, which has to be the best of the year bar none.

2) The Moon King by Neil Williamson

I’ve known Neil practically from the first con I ever went to, and so I felt particularly eager to see what he’d come up with for this, his first novel. I actually read The Moon King at the back end of last year, in ARC format, and was pleased to provide a blurb for it just prior to publication.

“Part dream, part nightmare, part memory, Neil Williamson’s Glassholm is a city that hovers on the brink of violent change. Through the intertwined stories of a cop fleeing his dark past, a young artist in rebellion against the social order, and an engineer who would most certainly not be king, Williamson has woven a story that teems with ideas and imaginative power. There is beauty in it, and strangeness, and page-turning adventure. The marvellous conceit at The Moon King’s core also conveys a powerful message about man’s relationship with nature and with his environment. The commitment shown to the characters by their creator is intense, and palpable. An intricately constructed, heartfelt novel that does its author proud.”

This feels like a worthy British Fantasy Award shortlistee to me.

3) Wake by Elizabeth Knox

I reviewed Wake for Strange Horizons back in February, and what an intriguing, original horror novel it is. I would love to see it on some shortlists, because it’s different, because it’s thought-provoking, because it stays with you. This is a book that still hasn’t had anywhere near enough exposure.

4) Shadowboxer by Tricia Sullivan

I wrote about Shadowboxer at my blog here. This novel presents as cogent an argument as any for why we need separate award categories in SFF for YA novels. As a subgenre, YA is important, increasing and with its own unique dynamic, and it’s high time it was granted this distinction at award level. Shadowboxer is a little too sparsely plotted in the final third, and it could have done with a bit more fleshing out in the sections set in Thailand, but as a portrait of a young woman in search of her destiny this is an engaging, emotional read for all ages. The material about women martial artists, and the martial arts writing in general, is superb.

And just to add that I’ve read a draft of Tricia’s forthcoming (adult) SF novel from Gollancz, Occupy Me, and it is amazing…

5) Cataveiro by E. J. Swift

I reviewed Cataveiro at my blog here. The thing that delighted me most about this novel – and there is plenty to delight – was the clear progress, in terms of narrative structure, in terms of emotional engagement, in terms of a maturing approach to the genre, that Swift has made since writing the first part of her trilogy, Osiris. If she’s made a similar leap forward in the third part, Tamaruq, to be published in January, then watch out, everyone, we have a major talent on our hands. Actually, I think we know that already. Cataveiro is skilfully written, energetically plotted and is a compelling reading experience. It will be fascinating to see where Swift goes next as a writer. I have the feeling she can achieve anything she wants to.

6) Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer

I wrote a little about Annihilation here, but not nearly enough. For something approaching a proper appreciation of the Southern Reach trilogy, go read Adam Roberts at Strange Horizons. This is a landmark work, and if it wins all the awards next year you won’t find any complaints here. None at all.

7) Maze by J. M. McDermott

I reviewed this for Strange Horizons here. I found this novel really hard going at first. Indeed, if I hadn’t been commissioned to review it, I might well have abandoned it. I am so glad I was reviewing it, and that I didn’t, because Maze is seriously good shit. For a good half of the novel you won’t have any idea what you’re reading – science fiction, fantasy, horror, new weird, wtf? But keep going and you’ll find that this is one of the most original and most daring novels of science fiction you’ll have read in months, if not years. It has things in common with Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, but if anything it’s even weirder than that. The writing, the execution, is flawless. We seriously need more writers with this kind of creative and intellectual audacity. I would love to see it get something approaching proper recognition.

8) Descent by Ken MacLeod

This is an odd novel, but I have a sneaking fondness for it and wish there were more writers willing to employ this kind of thoughtful ambiguity and quietness in their approach to SF. It’s the story of two childhood friends who may or may not have experienced a first contact with aliens. The moment has far-reaching effects on both their lives, but in differing ways. Set in a deftly, minimally realised future Scotland, Descent is the story of one man’s tortured search for the truth, with added Men in Black. It’s very much worth noting that no unknown first novelist would be able to get away with such meandering almost-plotlessness these days and still land a book deal, which, given the very real and very solid intellectual and political value of this novel should be a matter of keen regret and self-questioning within the publishing industry. Read it – we need more like it.

9) Memory of Water by Emmi Itaranta

With its flavour of weak tea, this YA-ish debut just wasn’t for me. I reviewed it for Arc here.

10) The Way Inn by Will Wiles

I reviewed The Way Inn for Strange Horizons and found it good. Very good, in fact. It’s cosmic horror, but that part of it doesn’t become apparent until near the end. For the most part, it’s a blisteringly deadpan (if that makes sense) unmasking of the horror we’re letting into our lives on a daily and increasing basis, the horror of corporate enterprise, of limitless car parks, of infinite Ballardian motorways. I would love to see The Way Inn on the World Fantasy Award shortlist, not least because it’s such a magnificent illustration of the versatility of the fantastic genres. Recommended.

11) The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell

I wrote something about The Bone Clocks here. I was very disappointed by this novel, which might best be summed up as kind of like Cloud Atlas, only not nearly as good.

12) J by Howard Jacobson

I wrote a bit about J here, too. If The Bone Clocks was my disappointment of the season, J was my unexpected find. One of those books that resoundingly repays the effort you (have to) put into it. It’s not science fiction though, not really. I’d be amazed to see this making it on to any awards shortlists, not least because Jacobson himself is so problematic. Do read it, though. There are so many interesting ideas here. And the way the novel actually manages to become involving and – nay! – emotional defies all logic.

13) All Those Vanished Engines by Paul Park

I reviewed this for Strange Horizons here. I love this book very much, and if it doesn’t sound contradictory I’d say I admire it even more than I love it. I also can’t help feeling an odd kind of affinity with ATVE, because it seems to me that Park was playing a similar game here to the game I tried to play in The Race, only playing it harder and fast enough to leave me puffing in his wake. I would hazard that ATVE is in fact harder to read – tough by virtue of its ironclad commitment to its own cause, sparing in its use of actual story, dense with allusion to the point of opacity. But God, it’s just so good. Seamless in its fusing of the real and the unreal, playful and knowing, yet absolutely serious in its use of science fiction, flawless in its construction, which is unassailably superb.

I guess it’s here that I do that thing they do at Wimbledon, where the loser shakes hands with the winner across the net. Park wins, three sets to one. Allan outclassed and outplayed.

14) The Blood of Angels by Johanna Sinisalo

I reviewed this book for Strange Horizons here. Falls very definitely into the interesting but flawed category. For me, the interesting quotient far outweighed the flaws, but sadly I think this novel will divide opinion too severely to end up on many awards shortlists. I would love to be proved wrong.

15) The Girl in the Road by Monica Byrne

I’ve written an article about this book which should hopefully be appearing in the next issue of Interzone. I found it to be far more a novel set in the future rather than a novel of science fiction, but there’s no crime in that, and I would recommend this original, beautiful and superbly executed novel to anyone and everyone. Even though I feel it dodges the issue science fictionally speaking, I still wouldn’t mind seeing it on some awards shortlists, for the outstanding quality of the writing and for the heartfelt honesty of its expression. I loved reading it. I still can’t help regretting that Byrne didn’t make more of the actual science fiction though, because the stuff that’s there – her vision of the future – is compelling, convincing and so economically conveyed there’s a lesson in there for all of us. For more on this outstanding debut, read Richard Larson’s insightful review at Strange Horizons here.

16) Tigerman by Nick Harkaway

‘Friends’ did not mean what it meant between adults, a balance of selves and strengths. It meant setting standards your children could not maintain, because if they could you wouldn’t need to set standards for them. It meant child-rearing by remote and by phone. It was an abdication, for parents who never wanted to admit they were grown-ups, who dressed from shops which were too young for them and listened to the new music to stay in the swim.

To do the job right was something else, older and different and patient and endlessly enduring, something which got stronger the more it was clawed and scratched, which bounded and uplifted and waited delightedly to be surpassed. Which knew and understood and did not shy away from the understanding that there would be pain. Which could accept shattering, could reassemble itself, could stand taller than before.

Tigerman isn’t a science fiction novel at all, but it is about genre, and it does use the materials of fantastika to tell its story. That story takes on the nature of heroism, fatherhood, and more specifically the dilemma of an ordinary man forced into being a hero for the sake of his son. Christopher Nolan’s Batman films attempted to show the man behind the mask, the truth of what being a superhero might actually involve. For me at least, they fail in this objective – they remain stolidly what they are, which is Batman movies. Tigerman, fascinatingly, moves one hell of a lot closer to Nolan’s objective. Sergeant Lester Ferris has seen service in Helmand and Baghdad, but he talks and thinks more like a wistful Colonial retainer from the late 1940s (and perhaps unsurprisingly displays a similarly casual, similarly unintended sexism). There is a lot about tea, and past mistakes, and muddling through. This book is so British it’s almost a parody, but it is saved from being that – just – by the author’s clear commitment to and passion for what he’s set out to do. The glacial pacing over the first third of the book is a real problem – I can imagine a casual reader giving up out of sheer boredom – but as the novel reveals more of its cards even that begins to make sense. I kept wanting to groan ‘oh no!’ at the novel’s Bond-film structure and plot arc, but of course that structure has been worked at and put in place, quite consciously, by the writer, and so I found myself grunting ‘hmm, clever’ instead. There’s not enough here about what must surely be the historical inspiration for the core story – the catastrophic desecration of Bikini Atoll through US nuclear testing and the forced resettlement of its inhabitants – and if I’d been writing the book myself I would probably have been more interested in the xenobiologist Kaiko Inoue than doughty Lester Ferris. But no novel can contain everything, and what Tigerman does contain is interesting enough on its own merits. I salute the author’s bravery in giving the reader only one half of the ending they might have wanted, and in writing a novel which is so clearly an expression of what he wanted to say at this point in his career. Tigerman is trying to do something, which is really one of the highest compliments a novel can be paid.

For a more in-depth and articulate discussion of Tigerman, see the recent book club roundtable at Strange Horizons. At a tangent from that, I might mention Harkaway’s own recent article for the Independent, in which he expresses gratitude and relief that Tigerman landed itself a shortlist place in the ‘Fiction’ category of the 2014 Goodreads Readers’ Choice awards rather than the ‘Science Fiction’ category:

“Talking to someone the other day, I mentioned that I’ll be on stage at the British Film Institute this month talking to William Gibson about science fiction films, and I saw his interest falter at the words. Science fiction wasn’t properly serious to him.”

Writer, beware! If I’d been having that conversation with someone, and their eyes didn’t light up in a blaze of hero-worship at the very mention of the name William Gibson, it would be their taste and judgement I’d be questioning, not my own, and no matter what their establishment clout. I might add that the establishment mainstream is a very fickle and – more importantly – often a very blinkered and conservative arena to be fencing in. You won’t find many people in the mainstream discussing Tigerman with the insight, knowledge and enthusiasm of these SH guys. The so-called wider literary world won’t get half your references and will miss quite a bit of what you were trying to do with Tigerman. The science fiction community will get it, and they will see why it matters. They will be actively looking forward to reading what you write next. Think on that, is all I’m saying.

Books I very much intend to have finished by the end of January in time for my BSFA nominations include Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel (I’ve just started this), A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar (up next), and Europe in Autumn by Dave Hutchinson, Further reading to be completed by the time the Clarke starts flexing its muscles in March will include The Peripheral by William Gibson and Lagoon by Nnedi Okorafor. I’m also intrigued by Wolf in White Van by John Darnielle and I really do need to read Bete by Adam Roberts, too.

This has been fun. Should I stick to a ‘genre only’ reading policy in 2015, or would that drive me nuts..?

.

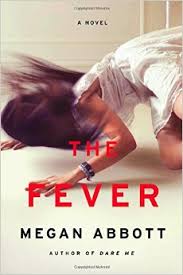

While I was reading I couldn’t help comparing this novel with The Fever, by Megan Abbott, another ‘odd’ crime novel (my favourite kind) that I read last month. Abbott’s mastery of the teenage mind is amazing – I’ve not read so accurate a transcription of the madness and malice and vulnerability of schoolgirls in a long time – and her use of language is superb. I’d say that The Fever is ‘better written’ than Everything You Never Told Me – Abbott’s turns of phrase are sublime, disturbing, and difficult to ignore – but that it is Ng’s book you will best remember, and enjoy, and recommend to others. In spite of everything, it ends well, it ends beautifully. A quietly resounding success.

While I was reading I couldn’t help comparing this novel with The Fever, by Megan Abbott, another ‘odd’ crime novel (my favourite kind) that I read last month. Abbott’s mastery of the teenage mind is amazing – I’ve not read so accurate a transcription of the madness and malice and vulnerability of schoolgirls in a long time – and her use of language is superb. I’d say that The Fever is ‘better written’ than Everything You Never Told Me – Abbott’s turns of phrase are sublime, disturbing, and difficult to ignore – but that it is Ng’s book you will best remember, and enjoy, and recommend to others. In spite of everything, it ends well, it ends beautifully. A quietly resounding success.