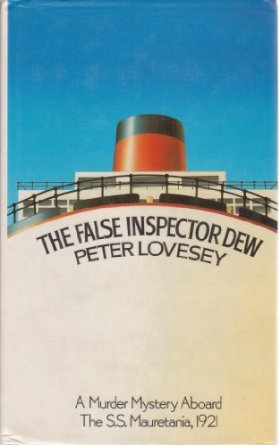

The Kills, by Richard House (2013)

We’re still only in September, and I have The Luminaries and The Goldfinch still to read, but I am going to be pretty gobsmacked if anything supersedes The Kills as my book of the year.

We’re still only in September, and I have The Luminaries and The Goldfinch still to read, but I am going to be pretty gobsmacked if anything supersedes The Kills as my book of the year.

Book 1: Sutler

“Although no one has seen him they have managed to bump into him twice? That is quite a coincidence. Mr Parson, how is your knowledge of the American Civil War?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Do you read historical fiction? Have you heard of a sutler? It’s a military term.” Bastian’s face pinched with a teacher’s concentration. “A sutler is someone who follows the military, they sell provisions, clothes, uniforms, food…”

“I’m sorry?”

“Sutler. Sutler. S.U.T.L.E.R. It’s from the Dutch. It means someone who does the dirty work.” (pp171-2)

We follow a fugitive from the Iraqi desert to Grenoble, where he disappears again, perhaps forever. A huge amount of money has gone missing. A man calling himself Stephen Lawrence Sutler is the obvious suspect, but who is playing him, and to what purpose? A team of film makers who encounter Sutler in Turkey become entangled in his affairs with disastrous repercussions for them all.

Book 2: The Massive

Even now the work bothers him in ways he can’t describe. Too much junk, too much dust, broken concrete, stuffed shopping bags, too much crap to properly know what’s being hidden. These buildings, he shakes his head. They clear them out, knock them down, and then build these superhighways right through them. A superhighway crashing right through some mediaeval sunscorched slum. (p283)

In a direct prequel to the events of Book 1, we meet the men of Camp Liberty. Rem Gunnersen’s hand-picked team of security and ex-servicemen have been charged with disposing of the vast acreages of dangerous garbage that is the ultimate undisclosed product of the Iraq war. The money is good, and they’re removed from the more obvious perils of the combat zone, but as the men gradually discover more about the dangers of the work they are engaged in, and the identity of the person who put them in their situation, relations between them begin to unravel. Meanwhile, at home in the States, Cathy Gunnersen begins an investigation of her own.

Book 3: The Kill

OK, there was the whole absurdity of it, obviously, it’s a crazy idea, but an appealing idea also, who doesn’t like the idea of two men, tourists, who kill, and take their instructions from a pulp novel. The very randomness of it. They come and go, and no one is ever caught – it’s morbidly satisfying, knowing you’ll never know. (p700)

Back in Book 1, a certain recent bestseller is passed around between various characters, a novel depicting a true crime investigation into a case whereby the author of a popular crime novel has disappeared in circumstances similar to those described in his own fiction. The novel is set in Naples, as is the fictional factual story that supposedly inspired it. It’s meant to be bad luck to say the title aloud. The person who originally owned the book in Book 1 has already disappeared.

Book 4: The Hit

“There was a murder.” The word was too ridiculous, spoken out in the sunlight, stupidly implausible. She can’t quite believe it, but doesn’t know what it would take to make such an event credible. Falling buildings, burning planes, deserts on fire, more plausible because of the scale. “They never found the victim.” (p891)

And in Book 4, the events of the novel that is Book 3 appear to be playing themselves out again, this time for real, in a different place and time and with a new cast of characters. Or is someone simply playing games with an urban myth? Some key characters from Book 1 reappear, still on the trail of Sutler, but there are now three Sutlers instead of just the one. We pick up their stories eagerly – but are we ever going to get the answers we’ve been looking for?

In her excellent recent review of Helene Wecker’s novel The Golem and the Jinni for Strange Horizons, Abigail Nussbaum makes reference to an article written for The Guardian by novelist Edward Docx in which he posits the over-familiar argument that novels employing genre materials will automatically prove inferior to the mainstream:

“It’s worth dealing with the difference again, since everyone seems to have forgotten it or become chary of the articulation. Mainly this: that even good genre (not Larsson or Brown) is by definition a constrained form of writing. There are conventions and these limit the material. That’s the way writing works and lots of people who don’t write novels don’t seem to get this: if you need a detective, if you need your hero to shoot the badass CIA chief, if you need faux-feminist shopping jokes, then great; but the correlative of these decisions is a curtailment in other areas. If you are following conventions, then a significant percentage of the thinking and imagining has been taken out of the exercise. Lots of decisions are already made.”

This argument is a nonsense based on a fallacy, namely the idea that a novel featuring an honest cop and a corrupt CIA chief, for example, must by its very nature find itself constrained within well-worn genre stereotypes, whereas a novel featuring a group of university students say, or TV execs wife-swapping in Hampstead, or a journalist facing dismissal because of phone hacking, will by its very nature offer a more rounded and psychologically realistic portrait of human interaction. It goes without saying that by-the-numbers fiction exists in all corners of the literary landscape – but to suggest that certain character or subject choices are intrinsically more prone to cliche or repetition or just plain bad writing has to be a false conceit. Either all writing exists on a level playing field – i.e, the success, failure, originality or otherwise of any given narrative is down to the skill and imagination of the writer, rather than the subject area in which he or she operates – or none of it does.

It would seem to me that the genre wars, as Nussbaum dubs them in her article, continue unchecked precisely because of a failure by both sides to acknowledge the simple and self evident fact that the use or non-use of speculative or thriller elements is in and of itself not a determining factor of literary quality.

It doesn’t help Docx’s cause that in spite what he says in the paragraph quoted above, much of his argument is based around the sub-standard output of hack writers such as Dan Brown, Stieg Larsson and Lee Child. (Child has to be one of the worst prose ‘stylists’ working today. I wish to God someone would call his bluff on that boast of his that he could write a creditable literary novel in three weeks – the results would make for grand entertainment indeed.) Docx is also seen to perform that neat trick so beloved of mainstream critics in hastily claiming those speculative or crime novels that disprove his argument (in this case Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment) for the literary mainstream. Thus critics like Docx bang on incessantly about the poor literary quality of works by Heinlein, Asimov, Campbell and Clarke, whilst insisting that Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four, Ballard’s Crash, David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas and Kuzuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go aren’t actually SF at all because they’re too well written. This kind of double standard is not just tiresome, it’s ridiculous.

I have a lot of sympathy with Docx’s frustration over the general crapness of much commercial fiction, but his lordly pronouncements on speculative fiction per se seem to be based far more around personal prejudice than on logic. Fyodor Dostoevsky proved again and again that a real writer can do anything he damn well likes with a basic thriller plot. Margaret Atwood, Patricia Highsmith, Joyce Carol Oates, Christopher Priest, Mike Harrison, Michael Swanwick and James Ellroy have all used genre materials to create literary masterpieces, and I could easily name dozens more who have done likewise. But for now I’m going to concentrate on naming Richard House.

Because House’s thriller-in-four-thrillers The Kills is a literary masterpiece. No amount of summarizing could adequately convey the power, complexity, literary elegance, and intellectual reach of this remarkable book. House has openly stated his admiration for Bolano’s great novel-in-five-novels, 2666 – a tough act to follow for anyone, but with The Kills, House has produced a work that is consummately worthy of its inspiration.

One of the things I dislike most about commercial thrillers is the way character motivation is so often twisted to fit the plot – characters do things not because they really would, but because the author needs them to. Nothing feels real, and because nothing feels real, nothing matters. The events that drive The Kills are strange, dark, frightening and mysterious – but not one thing that happens feels false, trite, predictable or unlikely. The plot – or should I say plots – seem to unfold with a flawless and inexorable logic from actions and decisions taken by characters who at every point in the story feel wholly three dimensional and real.

And this book is genuinely thrilling. As you might expect with a novel of this length (for those who don’t already know it’s 1,000 pages) its complexities take time to unfold and there is work to be done by the reader. You must come prepared to immerse yourself in this narrative, to devote yourself to it mentally for the time it takes you to read it. There will be moments of discomfiture – especially at the beginning – while you try to work out exactly where House is taking you, and for what purpose. But that is part of the joy of this book, and believe me when I tell you that every ounce of effort you put in will be repaid. There were moments in all four of the books when the hairs on the back of my neck literally stood on end as my eyes were opened to some new revelation or resonance, where I found myself racing through the pages, the pleasures of the prose now coming secondary to the simple and urgent need to know what was going to happen. This novel is long, but only exactly as long as it needs to be. I read a fascinating interview with Eleanor Catton at the weekend in which she compared long novels with DVD box sets in the way they offer the possibility of longer and more complex story arcs, of stories within stories and properly realised subplots. This is certainly true of The Kills. There are a lot of words here, but not one of them feels superfluous to requirements.

In matters of form, the book is a significant accomplishment. The four books are not so much linked together as enfolded in one another like origami. Resonances between them abound – not just going forward, but looking backward also. Even yesterday as I finished the book, I found myself cheering ‘oh YES!’ to a suddenly obvious parallel between Books 3 and 1 that I hadn’t noticed at all until that moment. There is a metafictional layering of narrative that – like the film of the book of the book in Books 1, 3 and 4 – results in what I can only describe as a millefeuille of storytelling, simultaneously singular and plural. In his review for The Telegraph, Jake Kerridge compares The Kills to ‘a dance that has been minutely choreographed’, a simile that feels particularly apt.

Kerridge’s favourite of the four Books would appear to be Book 2, The Massive, and if I were pushed to name my own favourite I think I might be inclined to agree with him. This damning indictment of Western actions in Iraq, the ignorance and greed that lay at the heart of the push towards so-called regime change and the thousand-and-one cock-ups in the wake of that, has the strength of purpose of the best kind of investigative journalism, with all the twists and turns (and horrific pay-offs) of a five-star political thriller. At the same time it is a deeply, deeply affecting literary novel about people. I’ll never forget Gunnersen’s men and I’ll never forget Cathy Gunnersen either. The Massive is less circuitous, less complex as narrative than the other three Books – its complexity lies in the way it interacts with the other novels – but this is perhaps where its strength resides. As a piece of political fiction it is a must-read. The Massive is an important book in its own right, by any standards.

It’s no surprise that much of the commentary on The Kills has tended to focus on the form it takes. But I wouldn’t want to end this review without talking about the novel’s language, which to me feels sublimely fit for purpose and in many, many places simply sublime. There isn’t a single bad sentence in The Kills. The novel’s pared-down, factualizing and dispassionate style has a documentary quality, a purity and a deceptive simplicity that is beauty in its most refined state, a kind of literary invisibility that had me in envy of this author’s brilliance on every page. That House loves words, the English language and the act of trasmitting thought and emotion through the act of writing is everywhere, everywhere in this novel, and I would like to close with a passage that, for me, summarizes not only The Kills itself, but the state of being a writer:

And this was gone. The precise description of the decor along a mantelpiece, Krawiec’s mother’s house, the petiteness of it, sullen and ordinary, of Lvov at night, how capsule-like the city seemed, of the people seated facing the windows at the respite home in Lvov, the women on buses, the silent trains and trams. Everything lost: the airport and how coming into it pitched through a layer of fog – fog so you knew you were in the heart of Eastern Europe, right on the edge of another period entirely – how this worked as an image of what he would and would not find – coming through fog, OK, not great, but apt. The petrochemical works, the roadways, the fields and fields shaved of produce, and the intensity of it all, that one man could come from this flat monochrome to a city so bumpy and opposite and butcher two people. (p714 – and don’t be deceived by that line about Krawiec butchering two people – like everything in The Kills, it doesn’t turn out the way you think it will… )

I was hoping to have this piece written and posted before the announcement of the Booker Prize shortlist this morning, but events, as they say, intervened, and the list was actually revealed about an hour ago, while I was still buggering about trying to get this finished. I’m not going to comment on the Booker shortlist at the moment, except to say that I feel devastated for House that The Kills isn’t on it. This doesn’t entirely surprise me – I said in an email to a friend recently that I doubted the judges would have the courage to include it (because of its length, because it’s a crime novel, because, because because) – but it does seem to me to be a criminal oversight. The Kills is a major novel, a major thriller, a major contribution to literature. I would urge you to read it.