The Eden Book Society is back – and I am delighted to announce my involvement with it! For more details, check out the EBS Kickstarter campaign here, where you can learn more about the Eden family, meet the Archivist, and claim your rewards.

Category: year of reading weird (Page 1 of 5)

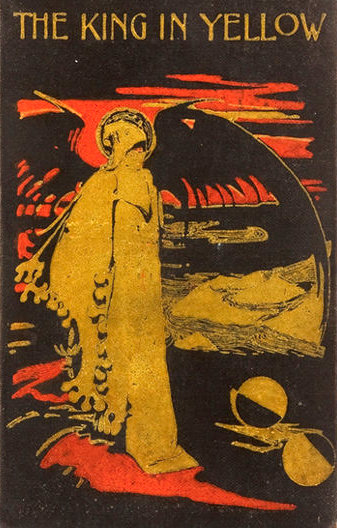

… and what better time to finally catch up with a classic of weird fiction that I have read a lot about but never read?

Robert W. Chambers’s The King in Yellow is one of those books. Written in 1895, this collection of stories has inspired and influenced writers all the way from HP Lovecraft to Nic Pizzolatto (and can you believe it has already been ten years since the first showing of True Detective??)

‘The King in Yellow’ is the title of a text-within-the-text, a play that brings insanity on anyone who reads it. I find it remarkable and rather wonderful, that the ‘cursed text’ trope is a hundred years old and more. So much of the power of the weird lies in its timelessness, the enduring appeal of its ideas and imagery. In the first story, ‘The Repairer of Reputations’, Hidred Castaigne is obsessed with the forbidden play, which he has read while convalescing from a head injury sustained in a horse-riding accident. Whether his madness stems from this accident or from reading ‘The King in Yellow’ is for the reader to decide. The glorious uncanniness of the story hinges on the fact that as readers we are drawn into Hildred’s delusion – that he is heir to a vanished kingdom – that we experience both shock and horror as his plan to assassinate his cousin in pursuit of his destiny comes closer to being enacted.

That the story is also science fiction – it is set twenty years in the future – adds another level of weirdness. The ‘future’ Chambers imagines is dark and sinister. There are suicide booths on street corners, a palpable sense of unease even in the most ordinary actions and interactions. All colours seem heightened, somehow. What I loved most about this story is how modern it feels.

Only the first four stories in the volume are explicitly bound by the ‘King in Yellow’ mythos. The remaining tales have often been dismissed or excluded from newer editions for not being weird enough, but I think this is a mistake. They are weird – very. There is a time-slip romance – a young man loses his way and ends up betrothed to a falconer in mediaeval France (very reminiscent of Le Grand Meaulnes) – and a brutal war story set during the Siege of Paris, which took place just twenty-five years before The King in Yellow was written. The chaos of war is written as a kind of haunting:

The fog was peopled with phantoms. All around him in the mist they moved, drifting through the arches in lengthening lines, then vanished, while from the fog others rose up, swept past and were engulfed. He was not alone, for even at his side they crowded, touched him, swarmed before him, beside him, behind him, pressed him back, seized and bore him with them through the mist.

Even in those stories where ‘lost Carcosa’ is not explicitly named, there is a sense that the realm of the lost king is there, waiting to reassemble itself, that the world we inhabit is the delusion, a temporary structure that might be swept away at any moment:

From somewhere in the city came sounds like the distant beating of drums, and beyond, far beyond, a vague muttering, now growing, swelling, rumbling in the distance like the pounding of surf upon the rocks, now like the surf again, receding, growling, menacing. The cold had become intense, a bitter piercing cold which strained and snapped at joist and beam and turned the slush of yesterday to flint.

That the overt weirdness of the stories recedes, reined back in the later tales to a suggestion, a supressed memory almost, makes the collection as a whole still more memorable and mysterious.

So much is left unsaid and unexplained. As if the writing of the book was interrupted, or prevented. It is unsurprising to me, that so many writers since have fallen in love with its atmosphere and – I use the term in its truest sense – obscurity. That they have felt bound to explore the yellow kingdom for themselves.

I may well become one of them…

Over the past ten years, we have seen a seismic upsurge of interest and enthusiasm for what has come to be known as folk horror, a peculiarly British brand of weird fiction characterised by subtle intimations of the supernatural, an understated delivery and most crucially an interest in landscape and sense of place. The folk horror revival has produced some excellent work, texts that have already earned their place in the canon and will endure as classics. It has also produced its own share of duds, derivative works that rely too much on familiar tropes and showing little inclination to break new ground. All literary movements tend to run to a law of diminishing returns, and such disappointments are inevitable. Which makes it all the more marvellous when out of nowhere something brilliant arrives to surprise you.

Ben Tufnell’s novel The North Shore is that rare beast, a work of folk horror that holds its own with the classics whilst exhibiting genuine points of difference, a radical literary sensibility combined with an old-fashioned appetite for the strange that will, I am sure, see me returning to this novel repeatedly for new inspiration.

The unnamed narrator – we learn only their initials – grows up somewhere on the north Norfolk coast (I am guessing Salthouse, or Stiffkey), a landscape of treacherous marshland and sudden storms. Alone on the shore during one such storm, the narrator unwittingly becomes a part of something extraordinary, an event that will mark their life while never fully revealing the true extent of its mystery.

Ben Tufnell is a museum curator and writer on art, so while it is not entirely surprising to find him bringing aspects of art criticism into his narrative it is entirely to be welcomed. His writing on the transformative power of Dürer and Bosch came as a real joy for me, and the landscape writing – a vividly sensuous evocation of liminal spaces – is truly exceptional.

To mix folk horror with film criticism and botanical illustration – yes, please! The narrator’s own uncertainty over what they have experienced, the ways in which the potentially treacherous landscape reflects their personal isolation – this is a timeless book, one that will outlast any fashion and repay close attention. The author’s refusal to provide any easy conclusion or explanation enhances the whole.

This elegant, thought-filled book has been an unexpected delight during a difficult week and I am already looking forward to Ben Tufnell’s next novel.

Today sees the appearance of Matt Hill’s long-awaited fifth novel. Lamb is published by the Liverpool-based independent press Dead Ink, the home of Naomi Booth’s Exit Management, Gary Budden’s London Incognita and Missouri Williams’s The Doloriad, provocative, unsettling works that challenge every aspect of the status quo. Given the nature of Hill’s literary identity – northern, speculative, discomfiting yet humane – it seems inevitable that this writer and this publisher would come together eventually.

Hill made his presence felt from the moment he arrived on the scene in 2013 with The Folded Man, which was a runner-up for the Dundee International Book Prize. Set in a disturbingly near-future Manchester and ‘starring’ the superbly dislikeable Brian, The Folded Man presents a fertile clash between gritty Gibsonian futurism and a distinctly home-grown eco-noir, an ambience that persists throughout his tangentially related 2016 follow-up Graft, which was a finalist for the Philp K. Dick Award.

The two novels that followed are equally distinctive. Climate change and the post-work environment become major themes in Zero Bomb (2019) in which grieving father Remi becomes drawn into a murky world of government surveillance and anarchist plots. The Breach (2020), published on the eve of lockdown and thus denied much of the attention it deserved, is a potent mix of evocative landscape writing and post-Brexit paranoia.

Indeed, what Hill’s books have in common is an obsession with the enforced inequalities and social divides – north and south, worker and manager, government and citizen – that have come to define our disunited kingdom in the present century. Hill is too young to have fully formed memories of Thatcher in government, but his political and literary consciousness have clearly been shaped by and within the long and continuing fallout from the 1980s.

This new novel Lamb, the latest chapter in Hill’s evolving oeuvre, is as brilliant as anything he has yet written, keeping faith with his core themes of future-shock, environmental degradation and the structural imbalances tearing at the fabric of our post-truth society. Following a family tragedy, teenager Boyd and his mother Maureen flee north from Watford to the village of Sile, an eerily closeted community where Boyd feels not just out of place but actively threatened. He knows there is something amiss here, whilst amongst certain elements of the townsfolk, the suspicion begins to surface that what is wrong in Sile is Boyd himself, or more specifically his mother Maureen.

With Lamb so newly published, it would be wrong of me to reveal much more about the exact nature of Boyd’s catastrophe, except to say that the journey he embarks on is one of radical transformation. The truth of who Boyd is – WHAT Boyd is – has far wider implications than the fate of one family, and as always with Hill, the vision presented to us within the pages of this story has more to say about our unreliable present than any possible future.

One of the most arresting aspects of Hill’s fiction is its boldness in incorporating dramatic speculative ideas into deeply human stories. From The Folded Man onwards, Hill has seemed compelled to place his characters in extreme situations, to test their resilience, and thinking about this today, the book that keeps coming to mind is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Like Shelley, Hill writes about responsibility, about cause and effect and the price of human arrogance. About technology run out of control, about the costly repercussions of moral failure.

Lamb is a unique blend of the personal and the political, the kind of work that reminds us how radical science fiction can be, how well it retains the power to shock and to surprise. A road trip like no other, Lamb will leave you thrilled, changed, unsettled, and still asking questions.

Even the floors in the houses are ugly. Old boards were ripped out to be used as construction materials, and you have to try hard to find a place where you can jump into your sleeping bag, zip up, and zonk out. The locals burned all the villages next to the wire with the enthusiasm of the thugs from Toretsk who dragged fragments of the downed Malaysia Airlines Boeing to local scrapyards – like a carcass, a mammoth, prey, whatever.

In 1972, a novel was published that is arguably one of the most influential science fiction stories of all time. Roadside Picnic, by the Russian writer-brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, tells of a world forever altered by a chance visitation. As readers, we never get to see the aliens – if there were any aliens – but we are offered glimpses of the things they leave behind. Objects saturated in mystery whose purpose is unknown, whose effects can be lethal, whose wider influence on Earth’s history and culture is incalculable and lasting. The contaminated zones are forbidden territory, fenced and guarded; for the stalkers who risk their lives and their sanity to penetrate these zones, they are something in the nature of an addiction.

In 1979 came Stalker, the film adaptation of Roadside Picnic, scripted by the Strugatsky brothers and directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. In the years since, the Zone has continued and deepened its hold over the imaginations of games developers, film makers, musicians, artists and writers. Especially writers. M.John Harrison’s 2007 novel Nova Swing, the second book of the Kefahuchi Tract trilogy and winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award, is an open letter to Roadside Picnic; Jeff VanderMeer’s bestselling Southern Reach trilogy equally so. There is something in the premise that seems uniquely magnetic and eerily mystifying, a postmodern spin on the trope of the ‘lost domain’ as first made explicit by the French writer Alain-Fournier in his 1913 classic Le Grand Meaulnes. Roadside Picnic offers a vision that is both beautiful and cruel, prosaic in its essence – some aliens do a pit stop, dump some trash – and yet shimmering with a sense of wonder that can never be extinguished or fully explained.

I first read Roadside Picnic in the early eighties and it has remained a touchstone text for me ever since, one of those few works of science fiction that I read – eagerly and indiscriminately – as a young person that has followed me into my life as an adult writer. I have read it half a dozen times and love it almost beyond reason. I need only to open its covers to fall immediately back under its spell. For me, it is the way in which the prosaic is enmeshed with the seemingly miraculous – with the vexed and corrosive nature of those miracles – that makes the novel so special for me. Add to that the unconventional manner of its storytelling, its moral ambivalence, the fact that it is a classic of Russian literature.

I also love Tarkovsky’s Stalker, which I approach as an entirely separate work, an adaptation of the Strugatskys’ novel in the true sense of the word, that is, a wholly new artistic endeavour inspired by an original. Tarkovsky does not really do characterisation – the people in Stalker are archetypes, a point underlined by the fact that the cast list does not give them names but designates them simply as ‘writer’, ‘professor’, and of course ‘Stalker’. It is the atmosphere of the film that compels, the mingled sense of beauty and threat, captivity and unbounded freedom that offers a hyper-real visual translation of what the Strugatsky brothers convey through the written word.

Anyone who comes into contact with Roadside Picnic seems to grasp instinctively that the book is important, that it offers a commentary on human existence, on the danger and pain and wonder of being alive. What then can I say about Stalking the Atomic City, a book that is as much a naked homage to Roadside Picnic as Stalker or Nova Swing but that has the distinction of being a work of non-fiction?

The book’s author, Markiyan Kamysh, is a Ukrainian writer. His father was a nuclear physicist and one of the ‘liquidators’ who risked their lives in order to clear up and lock down the exclusion zone surrounding the Chornobyl nuclear reactor following the catastrophic explosion and meltdown in 1986. Kamysh’s father died in 2003. Kamysh describes himself as ‘a writer who represents the Chornobyl underground in literature’. He might equally be called a stalker, one of the many dozens of adventurers, thrill-seekers, scrap metal looters, tour guides and misfits who since the turn of the century have been venturing into the exclusion zone, hiking and mapping, photographing and itemising its vast and hazardous spaces, often at risk of ruining their health, both physical and mental.

Most of them, perhaps predictably, are men; there is an element of stalking that seems to be little more than a dangerous and elaborate form of cock-measuring contest. There is more to it than that, though. There is poetry and there is horror. There is a vitality, a rawness, a sense of contact with an utterly new and uncharted space, a enclave of strangeness that might as well be an alien planet. There is, above all, the freedom that comes with casting off the directives of a world too heavily circumscribed by outside command.

Reading Kamysh’s book – part ballad, part Bildungsroman, part psychogeographical investigation – has offered me my most uncanny reading experience of the year, because it appears to reflect a version of reality first described in a novel of the imagination written fifty years ago, first lived by a film director who died from the cancer caused by the toxins that pollute the site of his most famous movie. The layers of literature contained within it – for Stalking the Atomic City is both a wholly new homage to Roadside Picnic and a demolition of it – now find themselves cloaked in a new, still more terrible reality as the zone itself has become part of a new battleground, a frontline in the war launched by Putin’s forces against the people of Ukraine.

Stalking the Atomic City reads as a dirty love poem to Roadside Picnic, just as Roadside Picnic reads as a shuddering premonition of Atomic City. Each seems to contain the other – not just in the likeness of the experiences they describe but in the beauty and intelligence of their language, their radical vision, the correlation of the word ‘stalker’ with the word ‘writer’.

The war in Ukraine is grounds both for anger and for deep grief. In its own impassioned, mysterious way, Stalking the Atomic City is an expression of that anger and that grief, as well as an undaunted assertion of Ukrainian identity. This book thrilled me and chilled my blood, even as I fell helplessly in love with it. I hope Markiyan Kamysh is doing OK, and that he is writing.

I have frequently been surprised, these past couple of weeks, by the way in which even seasoned literary commentators still slip into the habit of referring to Alan Garner as a children’s writer. I am sure I’ve said this somewhere before, but I continue to think of my first encounter with Garner’s work – The Owl Service, which I first read when I was around twelve – as among my most significant primary encounters with adult themes in literature. I found the book utterly compelling – but if you had asked me then what it was about I would have found it hard to answer. There was simply a feeling I had, a palpable sense of having touched something mysterious, timeless and possibly dangerous. I experienced the same feeling, albeit with a greater understanding of what was going on, both in me and in the book, when I belatedly caught up with Red Shift, some years ago.

As regards the Booker commentators, what on Earth is wrong with saying that Alan Garner is a writer who often centres young protagonists?

Which is exactly what he does in his 2021 novel, Treacle Walker, recently shortlisted for the Booker Prize, a fact that has made me feel more personally excited about the award than I have done since Anna Burns won it for Milkman back in 2018. The Booker has become generally much more innovative, inclusive and interesting in recent years, and I follow the annual discussion surrounding it with great enjoyment. Garner’s shortlisting though speaks to me personally. It counts, for me personally,. This is simply a feeling I have.

Treacle Walker tells the story of a boy, Joseph Coppock. Joe has recently been ill, and seems to spend a lot of time alone. Are his parents at work? Who looks after the house? We are never told. We live, for the duration of this short novel, entirely inside the world and mind of Joe as he encounters a mysterious rag-and-bone man, Treacle Walker, and falls into a daunting adventure that will alter his universe.

Treacle Walker speaks to Joe in riddles, an affectation he clearly finds simultaneously annoying and compelling. He is eager to learn the secrets the old man wants to impart to him, at the same time impatient, as any boy might be, to set his own stamp on the world, to interpret its signs and wonders in his own language. Most of the dialogue in Treacle Walker is conducted in the dialect of Garner’s native Cheshire, and one senses keenly Garner’s desire not to confuse or obfuscate but to set down, to save this unique language from annihilation in the twenty-first-century rush to refute the past. There is also a fierce feeling of privacy being accorded, the boy and the man who were always meant to come together sharing knowledge neither could fully fathom, until now.

It is notable that in the moments of highest tension and drama, the two cease with their mutual ragging and speak in terse, plain English. In these exchanges, it is almost as if the two are of a similar age and level of understanding.

As with all of Garner’s work, the action takes place against a vividly described, living landscape. One might almost say that Garner’s writing becomes the landscape, revealing it in all its aspects: peace, seclusion, discomfort, joy, alienation and terror:

But night was in the room, a sheet of darkness, flapping from wall to wall. It changed shape, swirling, flowing. It dropped to the ground and ruckled over the floor bricks; then up to the joints and beams of the ceiling; hung, fell, humped. It shrieked, reared against the chimney opening, but did not enter. It surged through the house by cracks and gaps in the timbers, out under the eaves. There was a whispering, silence, and on the floor the snow melted to tears.

This passage speaks to me particularly, both in its heady choice of words and in the symbols they carry. There have already been suggested many possible and plausible explanations of Treacle Walker’s meaning. For me, it is a book about the rising tide of chaos that accompanies change, the corresponding forces of growth and new imaginings that bring about progress. People have spoken of this novel as Garner’s last hurrah, a gathering together of his familiar themes, a farewell coda. It may be all of these things. Yet it is equally a work of bold experiment and dynamism, a book that makes use of ancient fable to speak to us in our own time with uncanny acuity.

Treacle Walker is tired, and Joe is ready and waiting to claim his future. As the two change places, or become one another, they mirror the unquiet yet seamless passing of one season to another.

A couple of weeks ago I had the great pleasure of talking with writer and folklore enthusiast Mark Norman, the creator and host of the very excellent Folklore Podcast. We had a wonderful conversation about The Good Neighbours, diving deep into the original inspiration behind the novel and the long tradition of fairy folklore within literature. The opportunity to talk about this aspect of the book with someone so deeply attuned to it was especially welcome, and if you’d like to find out more you can listen to the episode here. While you’re at it, you might also want to check out the wealth of resources available at The Folklore Network, including all previous episodes of the podcast. It’s an inspiration.

Talking of which, now seems like an excellent time to give a shout-out to Mark’s latest book, Dark Folklore. Written together with folklore historian and playwright Tracey Norman, this book is an exploration of the more sinister side of folklore and looks like an absolute must for anyone interested in folk horror, either from a reader’s or writer’s perspective. You can buy the book here.

Yesterday I had the great pleasure of taking part on an online symposium on the work of William Golding, organised by Arabella Currie and Bradley Osborne, under the aegis of the University of Exeter (nice to be back there, if only via Zoom!) This turned out to be one of the most inspiring and energising events I have yet taken part in, with engaging contributions from everyone involved and some excellent discussion. The artwork and storyboarding shown to us by Adam Gutch, who is developing an animated movie of The Inheritors, left us all feeling more than a little eager to see that project come to fruition. And the paper on the science fictional sensibility of Golding’s sea trilogy from poet and scholar William Stephenson was another highlight in a day that was all highlights. I had not realised Exeter boasts such a rich treasure trove of original Golding material, and the wonderful presentation from head of heritage collections Christine Faunch made me determined to visit the archive personally in the future.

My own part in the proceedings came soon after lunch. You might remember how my interest in Golding was reignited by the Backlisted podcast’s discussion of The Inheritors last year, in particular the contributions from Una McCormack on Golding’s place in the history of British science fiction. It was a real joy to be able to carry on those discussions with Una in person during our joint presentation, ‘Beyond Gaia: Golding and Science Fiction’. Una gave a fascinating talk on how Golding kicks away the genre scaffolding and dives deep into the heart of speculative ideas, and I followed this up with my own short paper on what some have claimed to be Golding’s most enigmatic novel, Darkness Visible, the full text of which is below.

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to everyone involved in making our event such a success – organisers, speakers and audience – and here’s hoping we can someday meet again in person for more discussion and fruitful sharing of ideas.

*

Alien Country: William Golding’s Darkness Visible and the anatomy of the strange

In his review of Darkness Visible for the London Review of Books in 1979, the Oxford scholar and critic John Bayley summoned the spirit of Borges to describe Golding’s fiction:

“Borges has written that the writer is like a member of a primitive tribe who suddenly starts making unfamiliar noises and waving his arms about in strange new rituals. The others gather round to look. Often they get bored and wander off, but sometimes they become hypnotised, remain spellbound until the rite comes to an end, adopt it as a part of tribal behaviour.

A simple analogy, but it does fit some novelists and tale-tellers, preoccupied in the midst of us with their homespun magic. They are not modish, not part of any literary establishment. Nor is there anything of the showman about them: Dickens was a magician in another sense, the sense that goes with the melodrama and music hall, and tribal magicians are not creators as Dickens and Hardy were. Their appeal has something communal, as the Borges image suggests, and the shareability of a cult. America lacks this type of magician – the shamans there are grander, more worldly, more pretentious – and the German-style version of Hesse or Grass is too instinctively metaphysical, not homespun enough. Richard Hughes was one of Britain’s most effective local magicians; John Fowles has become one; William Golding has had the status a long time.”

We might choose to quibble with Borges’s use of the term ‘primitive tribe’; we might equally dispute Bayley’s summary dismissal of American and German novelists as purveyors of magic. What makes Bayley’s review of Darkness Visible interesting to me – aside from the fascination of reading a piece of criticism contemporaneous with the novel itself – is how closely it coincides with my own view of Golding as one of what I have come to think of as the maverick strain in British fiction: novelists who, though seldom regarded as such, reveal a secret stratum of the fantastic amidst a literary geology more commonly described in terms of its obsession with novels of social mores, its tendency towards mimesis.

When American critics talk about the genealogy of science fiction they present us with a lineage that begins with the pulp magazines of the 1920s, that pays homage to the holy trinity of Campbell, Asimov and Heinlein. Fantastic literature written earlier – or that does not accord with a set of fuzzy and increasingly spurious set of definitions – is too often dismissed as ‘proto-SF’ or ‘not really SF at all’. Long before I had ever heard the name of Hugo Gernsback, or had any inkling that science fiction was supposed to adhere to any specific set of arbitrary man-made criteria, I was beginning to discover for myself a more home-grown, or to echo John Bayley homespun genealogy of the fantastic that appeared to have grown up organically, not from any pre-determined magic spell but from the independent-minded, endlessly curious and – yes – maverick spirits of the writers themselves.

I didn’t know Beowulf then but I did know Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights and The Woman in White. I knew H. G. Wells and his Time Machine, Aldous Huxley and his Brave New World, John Wyndham and his Kraken. As I grew older and read more widely I was delighted to discover echoes and resonances of these elder gods in the work of George Orwell, Iris Murdoch, Rumer Godden, Mervyn Peake and JG Ballard, John Fowles, Doris Lessing and Christopher Priest. These writers, it seemed to me, offered me a view of my native landscape and cultural background that seemed to accord more closely with my imaginative experience than either American science fiction writers – mostly aliens! – or the British mainstream literary canon.

An early and immediately beloved discovery in this hierarchy of misfits was William Golding. I would not like to guess at the number of times I read Lord of the Flies between the ages of twelve and twenty – I can only say that the story horrified, bewitched and inspired me in equal measure. I quickly went on to read Pincher Martin, equally wondrous and, to use a Golding word, weird. I have not counted Golding’s uses of the word weird in Darkness Visible; perhaps I should have done, given that no other word seems as apt to describe it.

Darkness Visible is thought of by many as the most enigmatic of Golding’s novels, which is interesting, given that it is unarguably the most modern. Published in 1979, Golding actually began writing it in 1955. In its first, tentative incarnation it was actually a science fiction story entitled Here Be Monsters, set in the future amidst a landscape of accelerating nuclear proliferation. It is famously the one work of his he consistently refused to discuss. It tells the story of Matty, an orphan child who stumbles from a burning bomb site at the height of the London Blitz, Sophy Stanhope and her twin sister Toni, prodigiously intelligent yet morally adrift, and Sebastian Pedigree, a paedophile teacher who is both disparaged and sheltered by the institution that employs him. The action centres upon the town of Greenfield, a suburb of London situated on the fault-line of post-war austerity and modernising, multicultural Britain.

Matty’s origins and parentage are never discovered – his constantly misplaced surname is used to symbolise the mystery of his fiery origins. As he grows towards adulthood, the facial scarring he incurred as a result of the bombing is a constant visual reminder of his apartness. Yet Golding leaves no doubt that Matty’s essential separateness from his fellows runs much deeper than physical appearance.

Matty’s vision of the world is as a mysterious other, a realm in which good and evil fight for supremacy, symbolised for him in the perfect shining roundness of the spherical glass paperweight in the window of Goodchild’s Rare Books. When he becomes unwittingly drawn into the simmering conflict between Sebastian Pedigree and the school’s headmaster, the fallout is tragic, impacting itself not only on Matty’s immediate future but ultimately on the fate of every character in the novel.

By contrast, the Stanhope twins Toni and Sophy view the world through a lens of cynicism shading to nihilism, the fruits of parental neglect combined with an innate surfeit of self-awareness. Toni runs away from home at the age of sixteen, quickly becoming involved with a terrorist group perpetrating outrages in Europe and the Middle East. Sophy’s spiritual rebellion appears more subtle, yet its end results are scarcely less disastrous. In literary terms, Matty and the twins are opposing devices; the scarred outcast Matty touched by the divine, the preternatural physical beauty of the Stanhope twins standing in pointed contrast to their moral vacuity.

For me though, Golding resists such simplistic analysis, and Darkness Visible is infinitely more complex, more ambiguous. Matty is morally good, but he is not a freethinker. He ‘does not get the code’ and so his goodness is rather like that of Frankenstein’s Monster: an innate innocence that is also rigid, shaped by and subject to the rules and rhetoric of organised religion and with a similarly unexamined outcome. Sophy Stanhope is a symbol not of evil but of existential disenchantment. She struggles within the bonds of existence as it is, strains towards something greater, a larger meaning to everything. She seeks in a way that Matty cannot – because she comes from a place of larger understanding, of participation in the world.

As a writer who veers instinctively towards the multi-stranded narrative, I find Darkness Visible to be a miracle of construction, its strands linked together not just through the reappearance of familiar characters but through the interacting perspectives of those characters. Hence we are told that Matty first encounters Sophy and Toni Stanhope as ‘two enchanting little girls’ gazing into the window of Goodchild’s Rare Books, or that Sebastian Pedigree’s return to Greenfield after his first spell in jail coincides with their mother Muriel Stanhope’s leaving.

Golding’s breaking of the fourth wall is a subtle thing, a slipping glimpse of postmodernism rather than a full immersion, yet it is a beautiful thing nonetheless and contributes significantly to the novel’s weirdness.

Darkness Visible takes place in the real world and has a sharp realworld awareness of contemporary politics and changes in society. Though the novel does contain turns of phrase and outdated usages that come across as dated and paternalistic in a modern context, Golding’s desire not only to reflect but to understand a rapidly changing world is powerfully apparent. The disenchantment and disillusion felt by the novel’s younger characters – with time on their hands and aching for purpose – seems both echo and indictment of the realworld violence perpetrated by European fringe organisations of the time, such as the Red Brigade in Italy, the Baader Meinhof gang in Germany, and the IRA in Belfast and on the British mainland. Sophy is an astonishingly vivid character, and Golding’s portrait of an exceptional woman is still something out of the ordinary. Similarly, his portrayal of Pedigree – ‘the sort of man whom a policeman feels in his bones should be moved on’ – is as shockingly direct as Nabokov’s depiction of Humbert Humbert in his masterpiece Lolita.

Yet Golding’s central literary purpose seems a million miles from social commentary. There is a mythic, interior quality to his narrative that renders it timeless. Sophy’s ‘desire to be weird’, her ‘hunger and thirst after weirdness’ is both an invigorating necessity and a deadly curse. Both Sophy’s narrative and Matty’s come suffused with the ‘homespun magic’ of which John Bailey speaks in his 1979 review. Even Frankley’s ironmongers – ‘a fine old establishment’ – has a feel of Steven Millhauser about it, or the porcelain showroom in Richard Adams’s ghost story The Girl in the Swing. Its infinite spaces, its cavernous lofts, its cobwebby rooms stacked with useless treasures seem suffused with the ability to become or to conceal a whole world, a snow-globe cosomorama of a life long past. Eventually, symbolically, we see the Frankley outbuildings being demolished in the novel’s Part 3.

The trajectory of the narrative – the overall story arc – is finally an affirmation of the novel’s weird nature, the fulfilment of its own prophecy. Edwin Bell, retired teacher and former colleague of Sebastian Pedigree at Foundlings School, believes Matty to be some sort of prophet, a Delphic oracle for our troubled times. Sim Goodchild, the proprietor of the bookstore whose business is failing, believes no such thing. For Goodchild, modern life is all hard logic. And yet we cannot help remembering Matty’s encounter with an official who tried to help him during his earlier ill-fated sojourn in Australia, a man who treated Matty as an equal, whilst at the same time warning him that his sacred message – his prescient foreboding of a planet in crisis – would forever be doomed to fall upon deaf ears.

The secretary takes Matty’s gestures seriously, yet stands apart from them. When he asks Matty if he has the second sight, if he ‘sees’, Matty replies: ‘I feel!’ an impassioned declaration that works equally as a vindication of the novel as a whole.

(NB: HEAVY SPOILERS AHEAD for Klara and the Sun.)

We could choose to speculate on why it is that two of the 1983 group of Best of Young British Novelists – frequently singled out by critics and commentators as the golden generation – happen to have brought out novels about artificial humans less than two years apart. Most likely it’s just one of those things: coincidence, a communal grappling with new ideas that are, as it were, simply around. Less to be debated is the fact that, in science fictional terms at least, the idea at the heart of the most recent novels by both Ian McEwan (Machines Like Me, 2019) and Kazuo Ishiguro (Klara and the Sun, 2021) is not new at all. Those who share an interest in such things mostly agree that the ‘threat’ from AI has much less to do with robot uprisings than with coporate data harvesting and the gradual shift within the workplace from human to artificial labour, with the seismic changes and potential inequalities this would and will bring. The idea of human beings coming under existential threat from actual AI replicants? Not going to happen. That both Ishiguro and McEwan have spent hundreds of hours and hundreds of pages heading down this particular ‘what if?’ rabbit hole brings us face to face yet again with the weird propensity of mainstream literary writers for reinventing the science fictional wheel.

A good part of the reason for this is that writers like McEwan and Ishiguro probably don’t read much SF. Most mainstream consumption of science fiction is through TV and cinema, which tends to lag behind the curve of science fiction literature by several decades. There is also the fact that McEwan especially has a habit of straining for topicality through battening on to shouty headlines and received opinion. Machines Like Me seems more interested in denouncing Brexit than in exploring AI; it is a weird novel, mostly irrelevant as science fiction and with a curiously old fashioned feel. Reading Klara and the Sun is a similarly confounding experience, though for different reasons. Ishiguro never chases after ‘relevance’ the way McEwan does, and in many ways this new novel feels uncannily similar to the seven that precede it. From the beginning of his career, Ishiguro has been singularly preoccupied with themes of appearance and reality, and so in Klara and the Sun we enter the land that is Ishiguro-world: a calm, apparently stable version of reality in which interactions proceed with courtesy and a certain caution. The surface reality of Ishiguro-world is unruffled, almost stagnant, yet beneath this surface we intuit hints and then increasingly larger glimpses of a scarier truth.

Ishiguro also has a penchant for not so much unreliable as partially informed narrators, people who are very much embedded in Ishiguro-world but who never fully understand it. In Klara and the Sun, our guide is Klara herself, an Artificial Friend who possesses the computational abilities of an advanced AI, whilst exhibiting a view of the world that is curiously child-like, unformed. AFs are in some respects similar to the Kentukis in Samanta Schweblin’s (much more interesting) novel Little Eyes: a consumer fad, the kind of expensive consumable you purchase for your kids, who then quickly become bored with it. In other respects, Ishiguro’s AFs are more complex and more sinister. We first meet Klara as she stands with her fellow AF Rosa in a shop window, hoping to attract the attention of potential customers. She is eventually purchased as a companion for a teenage girl, Josie, who lives with her mother outside of the city and who is suffering from an unnamed illness.

Klara has been specifically designed to serve and protect the child that chooses her. She never questions the world she inhabits, nor her role within it. As a solar-powered machine, she has a reverence for the sun, which for her is imbued with an almost god-like power. Throughout the entirety of the novel, we see only what Klara sees, go where she goes, though as her understanding and experience increases, so does ours. Through Klara’s immaculate recall, we get to overhear conversations between the adults in her orbit – Josie’s mother Chrissie and Josie’s father Paul, Chrissie’s friend Helen and her former lover Vance, the ‘artist’ Capaldi. Through these conversations, we come to learn that this is a deeply divided society, one in which genetically engineered or ‘lifted’ humans are offered every advantage in terms of education and prospects, with unlifted humans consigned to mass unemployment and more or less barred from higher education.

The ifs and buts around these issues remain unexamined. We come to understand that lifting carries some sort of extreme medical risk. Chrissie has already lost one child to the process – Josie’s older sister, Sal – though this has not dissuaded her from opting for the same treatment for Josie, and the mainstream acceptance of the dangers of lifting means that – presumably – death is now seen by society at large as preferable to not being lifted. There are tiny glimpses of hardship – a minor character called Beggar Man, a drab part of the city with a lot of barbed wire and boarded-up shopfronts, Chrissie permanently tired out from long hours at her job – though the characters we spend the most time with all live in spacious accommodation far from such deprivation and we never learn what Chrissie’s job actually entails. There is a depressingly facile passage about racially segregated outsider, i.e unlifted communities, though again we never get to meet any of these people other than Josie’s father. Paul is an engineer, and supposedly a man of uncommon intelligence, though that doesn’t prevent him from getting sucked into a preposterous scheme to cure Josie’s illness, a plan that should be patently absurd to anyone but Klara.

I was recently in the audience at an online event where Ishiguro described Klara and the Sun as the positive counterpoint to his darkly themed 2005 novel Never Let Me Go. I would go further, and say this book is Never Let Me Go, except with AIs instead of clones, eugenics instead of organ farming. There is even a wincingly uncalled-for repeat of Never Let Me Go’s central, fairy-tale premise of True Love offering a path to safety in a hostile world. Why Ishiguro considers the outcome of this new novel to be happier is a bit of a mystery, given what happens, and I’m not just talking about Klara’s ‘slow fade’. The conversations that take place between the adults in Klara and the Sun are conducted as a theatrical grotesquerie, using the kind of megaphone dialogue you might find in a particularly awful 1950s film, miles distant from what people might actually say to one another in real life. I have paused to wonder if such ineptitude might not be intentional, a kind of Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt. This at least might have been interesting, though unhappily and going by past experience I think it’s more likely that writing dialogue is an aspect of his craft that Ishiguro simply does not much enjoy

I am the last person to criticise a writer for choosing a close focus approach to science fiction. I mostly find wide-screen SF unutterably dull; books in which warring factions subject each other to offensively unrealistic acts of violence in their efforts to uphold or upend ‘the system’, in which characters spend pages spouting political rhetoric at each other or acting out social archetypes in a depressingly two-dimensional way can all go straight to Netflix so far as I’m concerned. The science fiction that interests me is centred upon convincingly drawn characters in imaginable situations, provocative ideas, life as it might actually be lived, together with the kind of literary articulacy we find in books such as the aforementioned Little Eyes. What I equally expect from this close focus approach though is difficulty, not in the sense that a book should be wilfully obscure, but that it should present us with complex moral choices and genuine dilemmas, conflicted characters, a level of narrative ambiguity that challenges the intellect.

On the surface and in outline description, Klara and the Sun might appear to possess such qualities. In the reading it is a series of evasions, perplexing only in the question of why so much attention will inevitably be lavished upon a text that is so deeply flawed. Klara and the Sun is a swift, easily digestible, stylistically pleasant read, but therein lies the problem. A novel that lays claim to themes of social exclusion, state-sanctioned eugenics and enforced mass poverty should not be pleasant, it should be confronting. At the very least, it should make some attempt to examine the questions it purports to ask.

And as for the ending? It’s Toy Story 2. Tell me I’m wrong.

Reading these two story collections back-to-back presented an eerily similar aesthetic experience to my encounter with Geen and Ferrante last week, only in reverse. Both collections deal with social change, buried secrets and personal crisis. Both employ elements of the fantastic to secure their effects. Yet the manner of approach, the mode of attack could not be more different, with the internal temperature of these stories, above all, providing a fascinating contrast.

Enriquez’s stories (translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell) take place against the shifting, unstable backdrop of dictatorships past. In ‘The Intoxicated Years’ we follow a group of teenagers as they confront issues of identity, addiction and sexuality in the years following the fall of the Peron regime. The political repercussions and personal reckonings that preoccupy their parents are to their children a matter of intense dullness, of ‘yeah, whatevs’; set against the agonies of teenage angst, the adult world even in its moment of greatest precariousness feels tedious, played out, irrelevant. Only as they grow older do they begin to understand how no one can live surrounded by such a society and emerge unscathed.

Other stories come populated more literally with ghosts from the past and monsters of the present, and Enriquez’s manner of merging the bitterest social commentary with elements of horror – see ‘Under the Black Water’ for a Lovecraft-tinged death cult (this story carries strongly resounding echoes of Clive Barker’s ‘The Forbidden’ aka Candyman) and ‘The Neighbour’s Courtyard for a hideously unsettling variation on the zombie story – is brilliantly handled. The stories’ boldness in confronting issues of violence against women is, for me, the strongest, most vital aspect of this collection. Women here struggle not only against weak, bullying husbands and cowardly fathers, they have the whole machinery of systemic machismo to deal with as well:

How many times had a cop like this one denied to her face and against all evidence that he had murdered a poor teenager? Because that was what cops did in the southern slums, much more than protect people: they killed teenagers, sometimes out of cruelty, other times because the kids refused to ‘work’ for them – to steal for them or sell the drugs the police seized. Or for betraying them. The reasons for killing poor kids were many and despicable.

My personal favourites among these stories are those in which the horror is less overt, where the line between the uncanny and the everyday is most cunningly hidden. ‘An Invocation of the Big-Eared Runt’ follows a tour guide as he entertains tourists with tales of the city’s most notorious murderers and serial killers, among whom the eponymous big-eared runt is most notorious of all, most especially because of the studied delight he seemed to take in the crimes he committed. As Pablo becomes ever more obsessed with the runt, the more the strain of his home life seems to tell on him. The story’s final lines are chilling, all the more so because they are inconclusive. The collection’s tour-de-force is ‘Spiderweb’, in which a young woman tied to a peevish and controlling husband goes on a day trip with him and her extravagantly charismatic and forthright cousin Natalia. Juan-Martin’s nagging and complaining is a constant irritation, and when their car breaks down on the return journey a reckoning seems at hand.

The landscape, atmosphere and tension of ‘Spiderweb’ are reminiscent of stories by Roberto Bolano in which the threat of violence, ever-present, hovers just out of sight. As soldiers of the regime torment a waitress at the neighbouring dining table, Juan-Martin’s unwavering sanctimoniousness threatens to push the threat over the edge towards calamity. Natalia though has her own ideas on how to deal with Martin. Once again, this story is all the more effective through leaving the reader to draw their own conclusion.

After the heat, dust and sweltering tension of Enriquez, I found the atmosphere of Mary South’s stories chilly at first; studied, beautifully turned and just a little too careful. I have seen other critics reference the SF TV series Black Mirror in their assessment of this debut collection, but the more I read of You Will Never Be Forgotten, the more this description seemed too pat, too obvious, and not wholly accurate. It is only really the first story, ‘Keith Prime’, that recalls Black Mirror, not to mention Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go, and in spite of being (as are all the stories) beautifully written, it is the one I find least interesting, precisely because its minimalist, soft-sci-fi tropes have been rehearsed before. South makes overt use of science fiction again in ‘To Save the Universe, We Must Also Save Ourselves’, in which the messy real-life dramas of actor Faith Massey are set against the unswerving heroism of her screen incarnation, Dinara Gorun, captain of the spacecraft Audacity.

Fans of the movie Galaxy Quest will find themselves chuckling happily along, and the story leaves no doubt it is doing its own thing by placing Faith’s battle with entrenched sexism – the most indestructible monster she has faced both onscreen and off – front and centre. Far stronger though are those stories in which South turns away from convention and pushes hardest against the boundary between the disdainfully ironic and the overtly uncomfortable. ‘Frequently Asked Questions About Your Craniotomy’ starts out reading like a conventional ‘list’ story but gradually strays into territory that is both horrific and heart-shattering. ‘Architecture for Monsters’ follows a journalist-fan of the groundbreaking architect Helen Dannenforth as she works to uncover the inconvenient truths at the heart of a genius’s life and art. ‘The Promised Hostel’ is, in common parlance, something of a mind-fuck, also a great story, while the title piece ‘You Will Never Be Forgotten’, in which a content moderator at ‘the world’s most popular search engine’ seeks to confront her rapist, is equally bold and ambiguous.

If South’s collection seems to lack the visceral, palpable urgency of Enriquez’s, this could well be down to the fact that I read the two books so close together. The elegance of South’s writing, the smooth turns from the domestic-banal to the queasily unnerving, her unswerving examination of aspects of the way we all live now makes You Will Never Be Forgotten well worth seeking out, and leaves the reader in eager anticipation of what South will write next. As for Mariana Enriquez, I understand her next novel is shortly to appear in English translation and I cannot wait. In the meantime, I would urge you to take an hour’s break to watch this conversation between Enriquez and M. John Harrison at this year’s (unavoidably Zoom-based) Buenos Aires Literary Festival. The insights into their writing lives, literary process and aesthetic outlook are many, varied and scintillating. Well worth your time.