The Lighthouse by P.D. James

I’ve just returned from a long weekend in Cornwall, visiting my mother and doing the kind of things I always look forward to during those visits – touring around the Lizard and Penwith peninsulas, checking out the latest art exhibitions. We were lucky with the weather and it was an invigorating, inspiring few days all round. Something else I look forward to when I visit Cornwall is the train journey. It takes eight hours, pretty much, door to door, which makes it a bit of a long haul. The upside, of course, is that there’s nothing else to do during those hours but read.

I’ve just returned from a long weekend in Cornwall, visiting my mother and doing the kind of things I always look forward to during those visits – touring around the Lizard and Penwith peninsulas, checking out the latest art exhibitions. We were lucky with the weather and it was an invigorating, inspiring few days all round. Something else I look forward to when I visit Cornwall is the train journey. It takes eight hours, pretty much, door to door, which makes it a bit of a long haul. The upside, of course, is that there’s nothing else to do during those hours but read.

I took two new SF novels with me. Both have been enthusiastically received, both look set to feature on awards shortlists in 2014. I found myself crushingly disappointed with both. I’ll have more specific things to say around Clarke time, no doubt, but for now I’ll summarize by saying that I found the first of these novels to be an accomplished and committed piece of work but not nearly as original as it thought it was. In the end, for me, it proved too shallow for its subject matter, all shiny surfaces and no characterisation. The second, whilst straining hard for Le Guinian reach and strength of purpose, struggled to come even close to Le Guin’s achievement, stylistically or intellectually. Reading it felt to me like being trapped inside one of the more interminable episodes of original Star Trek. One long infodump, once again zero characterisation, and tedious with it.

Have we lived and fought in vain, I grumbled to myself as The Cornishman finally pulled into Truro station. But the horror was not over. I looked forward to selecting something more inspiring to read from my mother’s shelves, but here also I would find myself thwarted. My mother is an eclectic and avid reader, but unlike me she is a convert to the Kindle. As she now does most of her novel-reading onscreen, the space given over to fiction on her bookshelves is decreasing. I couldn’t face Anita Brookner and I’d read all the E. M. Forsters, and so it was that I ended up choosing a 2005 novel by P. D. James, The Lighthouse. I could cover it for my crime blog, I thought, and by happy coincidence it turned out to be set in Cornwall.

I read a lot of P. D. James in my twenties, and enjoyed her a lot. In my memory, those novels of hers I liked best – Devices and Desires, The Black Tower, A Taste for Death, The Skull Beneath the Skin and especially the non-series Innocent Blood – had been meaty psychological studies tending towards weirdness and satisfyingly heavy on sense of place. I was curious to see how I might find her now. It had been well over a decade since I last picked up a PDJ, and I read differently now in any case. Everything I read, I read as a writer. I am looking for different things. I am definitely more critical, less easily satisfied.

The God of Bad Books clearly had it in for me this weekend, because reading The Lighthouse was not an edifying experience. The story, as in all country house murder mysteries and their many variants, is a simple one and none the worse for that: a famous writer, Nathan Oliver, goes missing on the exclusive Cornish island-retreat of Combe. Shortly afterwards he is found dead. Is it suicide, or murder? Inspector Adam Dalgleish and two more junior officers are summoned to find out. The small cast of suspects are introduced and questioned in the traditional way. More trouble ensues as old eminities are uncovered and the case is further complicated when Dalgleish suddenly goes down with SARS. This plot development in particular comes across as contrived and banal – three guesses which ‘superbug’ was hitting the headlines when James was writing this one. Rifling current news stories is always a risk for a writer – one wrong move and your book will appear catastrophically dated almost before it is published. P. D. James’s SARS subplot falls harder than a lead balloon. Sadly this is not the only problem with this novel.

As I recall it was PDJ herself who compared the country house murder mystery with the poetic form of the sonnet: far from being restrictive, having to adhere to a recognised plot structure is actually freeing and no bar to originality, no matter how many other writers have been there before you. I have no problem with that idea – you only have to consider the infinite possible variations of a 12-bar blues to see the truth in it.

But when a writer gets lazy, problems begin. James does not so much create a variation upon a theme as present us with another tired repetition of that theme, using masses of extraneous detail as a mask for clunky writing. We go along with it because we love the idea of the story and because we want to know what happens. Even when PDJ presented me with a completely redundant 30-page prologue (in which Dalgleish and his officers are (re)introduced and the scene set, all information I would encounter again in the following pages) I still wanted to know what happened. Two hundred pages and many needless repetitions, embarrassing passages of dialogue and teeth-grittingly out-of-touch social observations later I felt angry with and embarrassed for the writer and desperate to get the whole thing over with as soon as possible.

I had a similar experience recently when reading Barbara Vine’s The Minotaur, coincidentally also first published in 2005. I love Vine’s earlier novels – they’re richly observed, compelling, suspenseful, enviably fine work. But this one just seemed… half cock. The crises seemed false, the characters misjudged, and the moral climate inextricably and inappropriately immured in the 1950s. Thus in The Lighthouse we have PDJ attempting to bring her narrative up to date in small and largely insignificant ways – Dalgleish writes his reports on a laptop, people communicate using mobile phones – whilst failing utterly in terms of the overall ambience. Characters make reference to contemporary novels and television programmes, the author is not shy of dating her narrative specifically in the early 2000s – and yet this is still a world of butlers, boarding schools and housekeepers, of burning shame over illegitimate parentage, of adult offspring unconvincingly in thrall to despotic fathers. James speaks of ‘the race warriors’ and ‘the animal rights people’ in bland and occasionally offensive terms of received opinion rather than personal passion and one cannot escape the feeling that these were subjects she thought she ‘ought’ to include rather than issues she actually wanted to write about. I don’t even want to talk about her cringe-inducing characterisation of Emma Lavenham’s (lesbian) college friend, and I found her attempts to convey street vernacular particularly horrible. Here’s eighteen-year-old Millie, a runaway from Peckham who is treated by the rest of the assembled cast as if she were still in nappies, vehemently countering insinuations that the murder victim might have been interested in her sexually:

“That’s disgusting. Course he didn’t. He’s old. He’s older than Mr Maycroft. It’s gross. It wasn’t like that. He never touched me. You saying he was a perv or something? You saying he was a paedo?” (p235)

This might not be so bad, were it not for the fact that Millie alone is presumed to speak in this way, while everyone else, regardless of age or gender, continues to hold forth in the same pompous brand of BBC English like characters from Brief Encounter. Dalgleish’s deputy Kate Miskin is not that much older than Millie, yet her dialogue makes her sound like the headmistress of a pre-war girls’ grammar school:

“The vestments when finished must be heavy and valuable. How do you get them to the recipients?” (p312)

I don’t think I’d be alone in finding something of a credibility gap here.

There is a perfectly good story hidden at the heart of The Lighthouse, but the novel as it stands is not it. It’s careless, misjudged, cumbersome, and stuffed with unnecessary padding. It’s awful to see James struggling to make her work appear more socially ‘relevant’. Literary ventriloquism of this kind is invariably a mistake – James would do far better taking the time and trouble to write in her own voice, on subjects and about characters that genuinely inspire her.

It’s disturbing to note that if this were a first novel by an unknown writer, such bum notes would see it laughed out of court. (See Martin Amis’s Lionel Asbo for a still more egregious example of unearned approbation.) No writer should rest on her laurels, no matter how verdant. I admire P. D. James greatly for the determination she demonstrated in becoming a writer in the first place, for her tenacity and commitment, for the continuing pleasure she clearly takes in what she does. I only wish I could admire her actual writing more than I do.

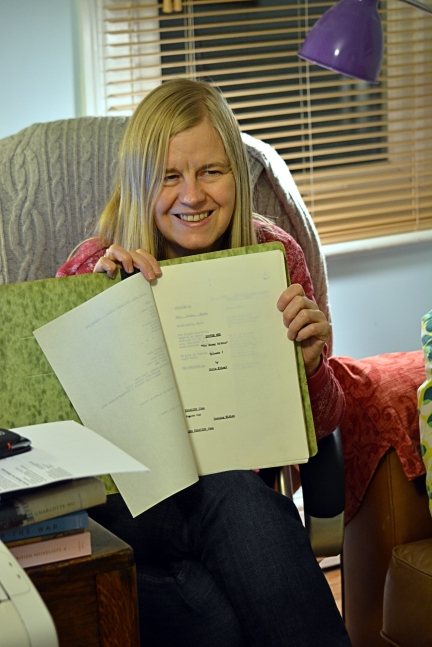

The Bowl of Cthulhu, by Monica Allan

Cottages, St Just

The Pier, Porthleven

Buildings, St Keverne