Dogmen have me surrounded. They yip and slaver, waving crude knock-off AKs, their bandoliers glittering in the Middle’s glass reflections of a red and bloated sun. The streets are swimming in their oil-black blood but still they mass, overcoming the city’s defences… The armies of the Augmented are already massing at the gates. The best we can do now is set the place to self-destruct, robbing them of their prize. If they seize control of the city and its weaponry, then there can be no hope for the human diaspora pouring from the gates. (Wolves p150)

The wolves in Simon Ings’s new novel Wolves are artificial constructs, figments of augmented reality that can be perceived only by those in possession of the most up-to-date digital hardware. They are also, more metaphorically, the forces of change, the barbarians at the gate, the overwriters of the physically real with the digitally invasive. They are the capitalist powers that seize ideas, like prey, and subvert them to their will. They are the demons of doubt that urge us to sell out our dreams.

The story of Wolves is narrated by Conrad, a guy in his forties who at the opening of the novel is just about to walk out of one life and into another. He’s been in a car accident, a traumatic experience for him, and one that leaves his girlfriend Mandy maimed for life. Her hands are sheared off at the wrists, and Conrad, realising only now that he has never truly loved her, sees in her ultra-sophisticated, (and to him) ultra-creepy prosthetic hands everything that has been going wrong with their relationship. Unable to confront his failure head on, he leaves Mandy without a word and heads north, seeking sanctuary with Michel, a childhood friend he has not seen in years. But there is a secret buried in Conrad’s past, and the renewal of his friendship with Michel is threatening to bring that secret to the surface. As matters complicate in Conrad’s present, the world he grew up in becomes increasingly subsumed in a future that is threatening to run out of control. In the age of augmented reality, is analogue actuality about to be permanently outmoded?

I am more or less exactly the same age as Simon Ings. Like him, I grew up in the 1970s and came of age in the 1980s. Like him, I am part of the final generation who will be able to say they experienced a childhood and adolescence that had no knowledge of the internet. By the time I left school, ‘A’ Levels in IT were just about becoming an option. Our school boasted two – yes, that’s two – computers. My brother lusted after a ZX Spectrum. I didn’t start using a computer regularly myself until I was 25. In a very real sense, this analogue world is still my world, the world of my groundwater memories and therefore the world that is the repository of my creative iconography. It is a world that certain friends of mine, people half my age, can barely comprehend.

In the world of Wolves, such facts are important. As SF readers and writers, we’re used to novels set in the future, books that extrapolate current technologies and either rebuild the world with them or run amok. We’re used to novels set in the queasy ambience of our present day – the continually birthing future, in other words – where we all share the ominous sense that anything could be about to happen and probably already is happening. What we’re less used to are novels that straddle that uneasy gap between the analogue past and the rapidly expanding digital future. If I were to name the salient feature of Wolves it would be precisely this, that it is that gap-bridger, a novel written from the mindset of one world whilst furiously trying to get to grips with the dawn of another.

The plot feels less important to this novel than its sense of place, its physical landscape, an anchor constantly threatening to be torn free. At its centre, both in actuality and as metaphor, is the river that runs through Conrad’s home town. Conrad’s childhood and young adulthood is shaped by the river in both good ways and bad, it teems with significance, yet by the end of the novel it has been subjugated and destroyed by what planners like to euphemise as forward progress. We see a force of nature trammelled, customised, sanitized, commodified. Such incidental and wholesale destruction of natural environments continues to be one of the most insidiously dangerous and under-documented desecrations inflicted upon this small island by governments driven by expediency and lethally unsustainable short-termism. The world of Wolves highlights such accumulating minor atrocities to powerful effect. Ings has described Wolves as a novel about the end of the world: what he shows us is not the atomic fire or meteor impact or mutant plague-type of catastrophe so beloved in the mansions of Hollywood, but a slow apocalypse, the inexorable concreting-over of everything that matters:

On the way back to Poppy’s house we detour by the river. Or we try to.

“Where is it?”

Though Michel knows the town better than I do, he is as shocked as I am by this change: “Fucked if I know.”

It’s not in flood. It’s not in spate. It’s not even here. It’s been paved over. Canalised. There is no millrace, and no bridge crossing the millrace, just a horseshoe of low stairs and a concrete ramp for prams and wheelchairs, and where the river used to be, a bicycle lane winds through landscaped parkland, and the underbrush and low trees that used to conceal the water have been cleared away and lime green exercise machines put in their place. It’s nothing like I remember. It’s devastating. In a way I can’t put into words, it’s almost the opposite of what I remember, and as we walk I can feel the memories of my youth begin to fizz and react in the solvent of this new real. I stare at my feet, afraid of how much of myself I am losing. (p210)

And where does Wolves sit, exactly, within the landscape of British SF? In an editor’s note to accompany the ARC (I don’t know if this personal endorsement has been carried over to the published text, but I think it would be a shame if it has not) Simon Spanton of Gollancz lays his own cards on the table:

This is a bleak but oh so powerful read. But other authors have created wonderful art from bleakness. Dare I saddle Simon with this comparison? Yes, why not. Wolves reminds me quite a lot of J. G. Ballard.

In his review for The Guardian, Toby Litt furthers the comparison, with the proviso that to describe Wolves simply as Ballardian would be to offer an incomplete analysis, citing precisely Ings’s skill as a ‘landscape artist – almost an SF Thomas Hardy’ in defence of his position:

…what is strongest in Wolves, and what gives the novel its greatest power to dominate the mind, is something it has in common with Graham Swift’s Waterland, Alan Warner’s These Demented Lands or Nicola Barker’s Wide Open. That is, an action that comes out of those scraggy edgelands where earth and water mix, where the shore is never certain. Ballard was never concerned about a sense of place.

Litt is absolutely right to talk about those scraggy edgelands, and might well have gone on to mention the fact that Wolves is a liminal novel not just in the literal sense, but also in terms of its relationship with science fiction. Wolves is a novel that inhabits the edge-of-genre, that infinite and flexible space between the soundly mimetic and the outright fantastic.

In its intimate relationship with the British landscape, its tense preoccupation with personal alienation and social change, Wolves is clearly related to and descended from the those texts that have been variously branded ‘miserabilist’ or ‘mundane SF’ (or more recently, by Adam Roberts in a review at his blog, ‘Glumpunk’) but that are arguably the true heirs to the British New Wave, the new New Wave, if you will, a kind of ultra-near-futurism that holds up a divining mirror to contemporary reality. We read Wolves and remember Christopher Kenworthy’s decaying Barrow-in-Furness in The Quality of Light, the stark weirdness of Nicholas Royle’s Counterparts, Joel Lane’s fury at Thatcher in From Blue to Black. But it is in its relationship with the new New Wave’s urtexts, M. John Harrison’s The Course of the Heart and Signs of Life and the story collection The Ice Monkey, that Wolves displays its allegiance most clearly. Harrison’s influence on Ings in Wolves feels pervasive and persuasive, a guiding principle. If Ings’s previous novel, Dead Water, is an intricate fugue, Wolves is its freewheeling toccata, a novel rife with personal anger that reads like it needed to be written. I sense that this is a transitional work for Ings, a move towards a fiercer, less restrained aesthetic and all the more effective for that.

One of the greatest dangers faced by British science fiction following the decline of the New Wave has been its co-opting by the commercial mainstream, its commodification at the hands of a nervous publishing industry in rabid pursuit of the next sure thing. As Ings himself recounts in his striking and bravely candid short essay at upcoming4me The Story Behind Wolves, when he first presented his then-editor with the manuscript of his new novel, that editor was less than enthusiastic:

My editor at the time told me Wolves was not publishable. He went so far as to say that publishing it would spoil my reputation.

Gather half-a-dozen writers together in a bar and the chances are they’ll all have a story like this. It’s sometimes hard to escape the feeling that British SF has suffered from a lack of direction in recent decades, a diminution of commitment arising at least in part from a willingness – fostered by an over-cautious publishing environment – to actively embrace the iconography and language of generic ‘sci-fi’ and all its bankrupt armoury of creative exhaustion. In a climate like this, it’s easy to forget that SF has been and always should be the literature of change, of innovation, of higher imagining. It’s in novels like Wolves – and in the willingness of the braver segments of the publishing industry to nurture and sustain their writers – that science fiction and the new New Wave will rediscover its purpose and its sense of direction.

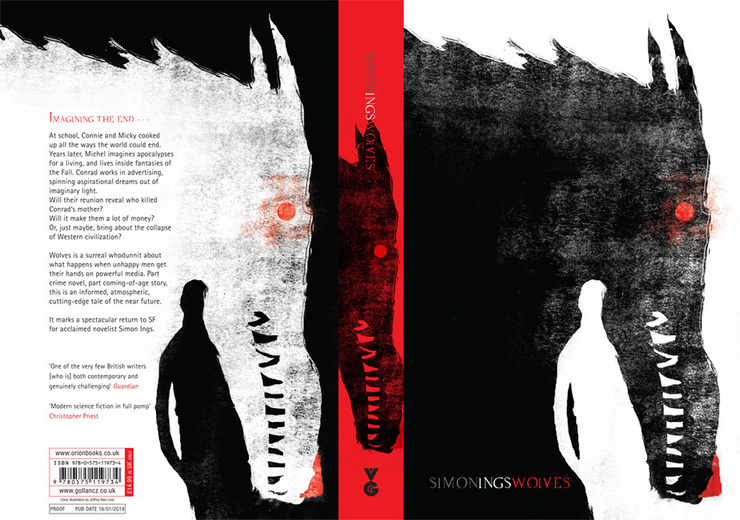

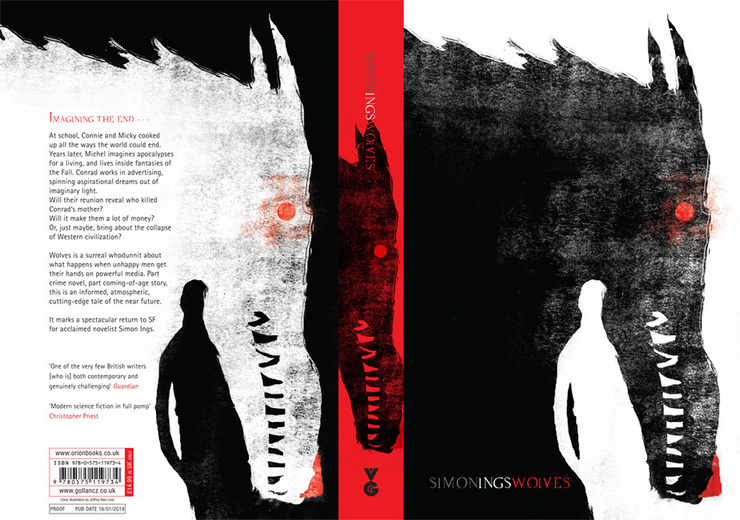

(Jeffrey Alan Love’s unique and beautiful cover for Wolves – if this doesn’t win a strew of ‘best artwork’ awards next year there’s no justice in this world. Read Love’s moving account of how he came to create this cover here.)

(Jeffrey Alan Love’s unique and beautiful cover for Wolves – if this doesn’t win a strew of ‘best artwork’ awards next year there’s no justice in this world. Read Love’s moving account of how he came to create this cover here.)

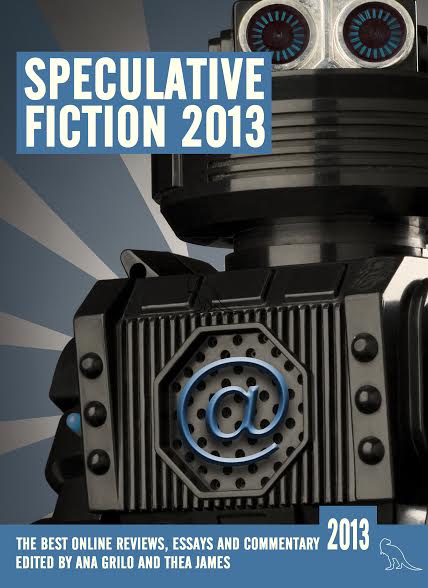

I’m very chuffed indeed to announce that I have a piece in the forthcoming Speculative Fiction 2013, an anthology bringing together the best SF essays, reviews and comment published online during 2013. Edited by the wonderful Ana Grilo and Thea James of The Book Smugglers, you can read the full (and awesome) list of contributors here.

I’m very chuffed indeed to announce that I have a piece in the forthcoming Speculative Fiction 2013, an anthology bringing together the best SF essays, reviews and comment published online during 2013. Edited by the wonderful Ana Grilo and Thea James of The Book Smugglers, you can read the full (and awesome) list of contributors here.