I am delighted to announce that I am now being represented by the very wonderful Anna Webber, of United Agents.

Month: January 2016

An essay of mine went up at Strange Horizons yesterday, in which I mull over the state of British horror and where we might be going with it. As part of that mulling-over, I took issue with a certain horror editor’s Top Ten list of favourite horror stories. For me, it seemed staid and just a little bit dull, given the wealth and breadth of horror literature we have to choose from. I also acknowledged how difficult it is to compile such a list, given the wealth and breadth of horror literature we have to choose from. Should we pick the stories that happen to be our favourites right now, or should we actively tend towards the conservative, selecting the works that have haunted our memories for decades, those stories we return to imaginatively again and again when we think about what most delights us in horror fiction?

A little of both, maybe. And fair is fair – if I’m going to pick holes in someone else’s list, it’s only right that I put up a top ten list of my own, to put my money where my mouth is, so to speak. There will doubtless be some who think I don’t go far enough in challenging the status quo here, just as there will be others who simply can’t believe I’ve not happened to choose one justifiably classic author or another. But that is exactly what these kind of lists are for, isn’t it? Discussing our choices, and hopefully challenging our perceptions of the subject in question. The main thing is that we have a conversation.

So who is my list for, primarily? At the most cursory level, I’d say it was for any horror reader or writer who feels curious about what kind of stuff another horror reader and writer happens to be into – you’ll get a pretty good idea of who I am as a horror fan from reading this list. I’d also say it’s for new writers: here is my best summary of the kind of work you need to be paying attention to if you want to get an idea of what horror is about and how you might fit into it. These ten works will give you a pretty good idea of the journey horror literature has been on and how it’s evolved. (It goes without saying that other fans, editors and writers might have differing opinions on exactly who is most important here and why.) I would also like to think that this list might be a starting point for people who think they don’t like horror: read the stories on this list, and perhaps you’ll end up with a pretty good idea of why you might have been wrong, and where you might go next to feed your growing enthusiasm.

Who knows – you might even end up compiling a list of your own…

And so here goes with my top ten. I’m going to try and lay these out in the order I might arrange them if I were editing an anthology:

- The Willows by Algernon Blackwood (1907). This is a classic work of English weird fiction. Two friends travel down the Danube in a rowing boat and become ever more fixated upon the landscape they pass through, convinced of its malignancy and possessed by it. An incredibly modern, prescient work of cosmic horror. Lovecraft admired this story tremendously and for me it signals the passage from the more buttoned-up, Jamiesian type of Victorian ghost story to the psychological idiom. A story that can be savoured time and again.

- The Ruins of Contracoeur by Joyce Carol Oates (1999). Joyce Carol Oates is thought of by most people as a mainstream literary writer. In fact, she’s one of the most important horror writers working today. A good chunk of her output – story collections such as Haunted, novels such as the Stoker-winning Zombie and the epic vampire novel Bellefleur – is specifically horror anyway, but more than that, everything she writes carries more than a touch of the gothic. Together with Iris Murdoch, I would have to cite JCO as the writer who lies closest to my heart, the writer I turn to when I want to regain a sense of where I stand as a writer. It’s hard to pick just one story to list here, but I’m going with this marvellous novella, a weird and unnerving offshoot from Bellefleur, because it’s the first Oates I ever read and it made me fall in love with her writing there and then. For a neat introduction to Oates and her importance to horror, I’d recommend this great little essay by Paula Guran.

- Welcomeland by Ramsey Campbell (1988). Arguably the most important British horror writer of the postwar era, Ramsey Campbell’s stories and novels carry echoes of the earlier weird fiction that has clearly worked a profound influence upon their author. Yet they are also grimly, often brutally of today: angst-ridden, bleak, alienated and genuinely terrifying. No one explores despair – both existential and circumstantial – like Campbell, and this story of a man returning to his home town bears all his trademark themes. Campbell’s layered use of language to create a sense of entrapment is pretty much unique in all of horror and I would say it’s essential for anyone interested in writing horror to read him. (NB: He can also be really funny.)

- At the Mountains of Madness by H. P. Lovecraft (1931). I’ve been thinking about Lovecraft a lot recently, and rereading him a bit, and I’m coming to the conclusion that this ‘terrible wordsmith’ business of which he is routinely accused is received opinion: people keep saying it, therefore it must be accurate. But whilst it’s true that HPL does not always know when to end a sentence, and he’s not so good on dialogue, when you go back to the writing itself, you’ll perhaps be surprised to find how evocative, precise and beautiful it often is. Take this passage here from At The Mountains of Madness: ‘The last lap of the voyage was vivid and fancy-stirring. Great barren peaks of mystery loomed up constantly against the west as the low northern sun of noon or the still lower horizon-grazing southern sun of midnight poured its hazy reddish rays over the white snow, bluish ice and water lanes, and black bits of exposed granite slope. Through the desolate summits swept ranging, intermittent gusts of the terrible Antarctic wind, whose cadences sometimes held vague suggestions of a wild and half-sentient musical piping, with notes extending over a wide range, and which for some subconscious mnemonic reason seemed to me disquieting and even dimly terrible.’ Because so much of contemporary western horror literature arises from Lovecraft, I would say that insofar as anything is essential reading for anyone interested in horror fiction, Lovecraft is it. (And pssst – his stories are highly entertaining.)

- The Lottery by Shirley Jackson (1948). As with Iris Murdoch’s early fiction, I’m always amazed when I’m confronted by the date-stamps on Shirley Jackson’s stories, because their ethos is so fiercely, so uncompromisingly modern. ‘The Lottery’ truly is a horror classic, and whilst its by no means the oddest or even the best of her stories, it’s a wonderful introduction to the art of a writer who could perhaps be described as the Katherine Mansfield of horror, bringing strange fiction out of the gentleman’s club and into the home. (In fact, Katherine Mansfield’s own 1912 story ‘The Woman at the Store‘ could itself easily qualify for inclusion on this list.) I’ve read this story more times than I can remember, yet it never loses its power to shock and delight. You can’t not love it.

- The Buffalo Hunter by Peter Straub (1990). Often seen as standing in Stephen King’s shadow, Straub has written fewer novels but their overall consistency – not surprisingly and for me at least – is finer. Ghost Story and Shadowland are colossi of the genre: novels both intellectual and visceral that you can read again and again and never quite come to the end of. I love his work. This novella is so weird and so disturbing and it showcases Straub’s writing and style to beautiful effect. In fact, go away and read the entire collection from which this story is drawn, Houses Without Doors – it’s one of my favourite story collections ever. For more on Straub, there’s an informative essay by Gary K. Wolfe and Amelia Beamer here.

- Riding the White Bull by Caitlin R. Kiernan (2004). I first read Kiernan – her story ‘Valentia” – in one of the Jones/Sutton Dark Terrors anthologies and, as with Oates, I knew at once that here was a writer who spoke to me directly. Her confessional style, combined with the beauty of her language, make her dear to my heart in a way that few other writers are. I wanted to include The Dry Salvages here, because it’s perfect and I wish I’d written it, but it’s another novella and I have the feeling I’ve sneaked in too many of those already. ‘Riding the White Bull’ contains many of the same themes as The Dry Salvages – alien contamination, existential dread, the end of the world as we know it – but for the purposes of this listing it has the advantage of being shorter.

- The Swords by Robert Aickman (1975). How to explain Robert Aickman? He’s often grouped together with M. R. James and Arthur Machen as a ‘master of the English weird tale’ and indeed Aickman does belong to – or rather issue from – this tradition. There’s more, though. His stories belong to a strange, indeterminate time for horror fiction, which unsurprisingly fell out of fashion after WW2, and did not truly arrive in its various modern incarnations until the publication of Stephen King’s Carrie in 1974. What permeates Aickman’s fiction most of all is a sense of disappointment, of washed-upness: the postwar ‘never had it so good’ utopia has failed to arrive. In Britain there’s a mood of confusion and displacement in the aftermath of empire. Where now? Aickman’s protagonists seem to be asking, and none more so than the travelling salesman who is the ‘hero’ of ‘The Swords’. In its depiction of decay and disillusionment, Aickman’s fiction provides something the English weird tale had never attempted up till then: a version of the dirty ‘kitchen sink’ realism we see in the mainstream novels and films of the period. It also directly paved the way for the weird fiction of writers from the so-called ‘mundane’ school such as M. John Harrison, Nicholas Royle and Joel Lane.

- The Devil in America by Kai Ashante Wilson (2014). It was this urgently compelling story, nominated for both the Nebula and the World Fantasy Award, that introduced us to the art of a writer who promises to be genuinely important to the field. I’ve recently read his follow-up, the dark fantasy (you could almost call it horror) novella The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps, and found it equally assured, even more innovative in terms of its language and construction. It’s always a joy to discover a writer this good, and ‘The Devil in America’ deserves all the praise it has garnered. A sort-of werewolf story, it exposes some of the darkness that lies at the heart of American history. It is also a very fine example of the new and more diverse writing that is starting to reinvigorate American fantasy.

- Her Deepness by Livia Llewellyn (2010). American horror fiction seems to be in a particularly healthy place at the moment, with a veritable tribe of newer writers such as John Langan, Laird Barron, Nathan Ballingrud, Damien Angelica Walters and Sarah Langan producing work of high literary quality and chilling depth of field. Of all these New Lovecraftians, perhaps the greatest is Livia Llewellyn. Her story ‘Horses’ is one of the starkest and most upsetting pieces of science fictional horror I’ve ever read, but I’m plumping for Llewellyn’s novella Her Deepness as my current favourite of her stories, because of the beauty of its language, the completeness of the world it evokes, and because it’s just fantastic. I’ve never read a duff sentence from Llewellyn. She is a major talent.

APPENDIX – BONUS MATERIAL: Stephen Jones added two extra Ray Bradbury stories to his top ten, so I’m damned if I’m not sneaking in two extra stories of my own!

- In a Falling Airplane by Otsuichi (2010). The Japanese horror tradition is a lifetime’s study in itself, and as a reader I’ve only just begun to brush the surface of it. There is something antic, something anarchic and deeply unsettling in the stories I’ve read thus far that leaves me definitely wanting more. We already know that japan leads the world in the jagged brilliance of its horror cinema, and there’s something of that same bizarro quality in Otsuichi’s fiction. His stories really ought not to be funny but they often are. They can also feel desolate, perched on the very edge of the abyss. I love the whole collection, Zoo, from which ‘In a Falling Airplane’ is drawn, and would recommend it as a starting point for getting to know what J-horror is all about.

- Pan by Bruno Schulz (1934). European horror, so dear to my heart, so utterly vital for the growth of the genre, so often forgotten in discussions of the literature. The best known writer of the European weird is probably Franz Kafka, but there are also amazing lesser known voices such as Friedebert Tuglas, Stefan Grabinski, Robert Walser, Thomas Bernhard and Gabriele Wittkop who are equally worth getting to know, not to mention contemporary writers such as Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Anna Starobinets and Karin Tidbeck. The prince of them all is Bruno Schulz, whose stories are perfect gems of strangeness and ambiguity. It’s almost unbearable to read him, knowing how his life and career were cut short, knowing what we lost when we lost him, but at least we have the stories we have: luminous, humane, resplendent in their strangeness and beauty. ‘Pan’ is just a few pages long but no matter – once you’ve read it, I guarantee you’ll want to seek out everything Schulz ever wrote and make loud, obsessive noises about it to every other horror fan you meet.

What strikes me most harshly as I look back over this list is the writers who aren’t on it. How can I justify including both Caitlin Kiernan and Livia Llewellyn, when that means denying a place to Kelly Link, whose shivery brand of horror is one of the most unsettling and original around? How can I not have included Kaaron Warren and Margo Lanagan, who are two of my favourite horror writers working today? How could I not have found room for ‘Caterpillars‘, a weird little tale from E. F. Benson that I like better than a lot of M. R. James and that has equal rights to be here as representative of the classic ghost story tradition? There’s a fantastic novella by Tade Thompson that would absolutely have been on here but can’t be, because it hasn’t been published yet. Likewise any of the stories from Helen Oyeyemi’s new collection, which isn’t out until April. And what about the two magnificent anti-horror stories, each in its own way representative of metafictional horror and each adored by me, Roberto Bolano’s ‘The Colonel’s Son’ and Joe Hill’s ‘Best New Horror’? What about Thomas Ligotti’s lifelong, ongoing dialogue with H. P. Lovecraft? What about the densely interwoven, experimental horror fictions of Michael Cisco and J. M. McDermott? What about Nnedi Okorafor’s phenomenal ‘Spider the Artist‘? These exclusions hurt, and if you think that my mentioning them here is just a sneaky way of getting them in under the wire, you’d be right.

A top ten should be what it says it is though (or almost), so I’ll leave it at that. Anything else would be cheating. If you don’t like it – and even if you do – why not get down to business compiling your own?

(Editors: Penelope Lewis and Ra Page)

This is the latest in Comma Press‘s series of short story anthologies exploring specific areas of science and scientific thought through the medium of fiction. Each writer is paired with a scientist working in the particular area they have chosen to investigate, with the scientist afterwards offering a commentary on the completed story. It’s a unique and intriguing concept – putting the science back into science fiction, you might say – and the afterwords here are without exception fascinating, offering a wealth of information and specific insights. The introduction to the anthology also, with its illustrative graphs and explanation of what our brains are actually doing while we sleep, is essential reading.

This is the latest in Comma Press‘s series of short story anthologies exploring specific areas of science and scientific thought through the medium of fiction. Each writer is paired with a scientist working in the particular area they have chosen to investigate, with the scientist afterwards offering a commentary on the completed story. It’s a unique and intriguing concept – putting the science back into science fiction, you might say – and the afterwords here are without exception fascinating, offering a wealth of information and specific insights. The introduction to the anthology also, with its illustrative graphs and explanation of what our brains are actually doing while we sleep, is essential reading.

I must add though that for me personally, sampling the afterwords immediately after reading each story proved distracting, breaking the spell the story cast – rather like seeing an over-eager zoologist rushing to dissect the carcass of some small and beautiful animal, when as a naturalist, all I really wanted to do at that point was to observe the creature in its natural habitat. So whilst I’d recommend these afterwords wholeheartedly on their own terms, I’m not going to discuss them here, and would personally suggest saving them to read separately, once you’ve had time to properly appreciate these delicate morsels of fiction and the games they play.

And so then to the stories! In order of the Table of Contents, here we go:

- My Soul to Keep by Martyn Bedford (Afterword by Prof. Ed Watkins). Kim is a sleep technician, working in a sleep lab alongside Dr Aziz. They’re caring for and seeking information about Charlotte, a young woman diagnosed with Persistent Hypersomnic State. Charlotte has been suffering from depression and the amount of time she spends asleep has been gradually increasing. As the story opens, she’s just coming up for a full year without waking. As a ’21st Century Sleeping Beauty’ she has attracted a number of fans and acolytes, all of them women, who have taken up residence in a makeshift camp outside the sleep lab. “I log the data sets,” Kim informs us. “It’s what I do. What we do round the clock. Polysomnography, each 12-hour block of recorded information processed and analysed, every variation in the pattern and physiology of her sleep pored over for signs of change or clues to PHS. There never is any change, though. Charlotte’s sleep is as remorseless, as featureless as a desert.” I really liked this one. It’s a delicate, subtle story, exploring the lives and emotions of Kim, who has two sons of a similar age to Charlotte, and Charlotte’s mother Evelyn, who wants to withdraw her daughter from the program and take her home. There’s a restless, uneasy quality to Kim’s thoughts as she finds herself drawn ever deeper into Charlotte’s world. A meditation, perhaps, on how the stresses of the modern world impact upon our ability to process them.

- Left Eye by Adam Marek (Afterword by Dr Penelope A. Lewis). “Nancy puts her hand on Left Eye’s hot shoulder. The strength in him. That wizened baby’s face. Moments of wishing she wasn’t here.” We are in the near future. Nancy is an expert in Targeted Memory Replay, a technique whereby programming the sleeping brain to recall events or sensations experienced during waking hours can help to alleviate the symptoms of PTSD. Up until recently, Nancy has been working with soldiers returning from the combat zone. When a private company offers her a lucrative new job opportunity, she accepts with alacrity – only to discover that her new test subjects are being experimented upon without their consent. Anyone who has read Karen Joy Fowler’s novel We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves will guess what the twist is here, and Marek’s story is equally devastating, equally morally complex, though on a smaller scale. A difficult, essential read, with no easy answers offered. The character of Nancy is brilliantly evoked in just a few short pages.

- A Sleeping Serial Killer by M. J. Hyland (Afterword by Isabel Hutchinson). A writer, Maria, explains to a psychotherapist she meets by chance in a cafe how she believes her violent nightmares are a kind of safety valve, siphoning off her rage and trauma and leaving her free to live a well adjusted life. ‘Even after an especially gruesome dream I wake in a mood of ‘lucid indifference’ and this cycle started when I was a child. From about the age of seven I was certain that I wouldn’t end up like ‘them’, my family, and that my nightmares weren’t a bad thing but a good and special trick that my brain played to make me tougher’, explains Maria. In her dreams she’s a serial killer, and that’s where this alter ego will safely stay. This is a fun one, a snarky little piece of metafiction – the story’s narrator and author share the same name – that nests its layers of unreality like glittery shreds of wrapping paper in a game of pass the parcel. There is serious intent here of course, but Hyland seems determined not to let us get too earnest about things by constantly undermining her clever little edifice with the worm of dark humour. I love the way this story is written.

- The Rip Van Winkle Project by Sara Maitland (Afterword by Prof. Russell G. Foster). The Greek gods Hypnos, Morpheus and Circadia call a meeting to discuss the worsening state of the world, which Circadia puts down to a wholesale human rejection of the dark. ‘It isn’t about money,’ Hypnos agrees. ‘They’re bullying each other into working inefficiently and for far too long for free. Even when they aren’t working they are up all night – shopping, something called ‘onlining’, even just staying awake to watch television shows they say are rubbish.’ Meanwhile, teenagers Sally Brampton and Matt Oliver go unwillingly to school, grouchy and resentful after being pulled from sleep by the demands of a world they are in no rush to join. Rooted in the natural world and spiritual contemplation, this witty and humorous story is everything we might expect from Sara Maitland. Rich in poetry and mythic imagery, this is a meditation on the restorative properties of sleep and the power of dreams – but not only dreams, as Circadia keeps reminding Morpheus – to return us to a state of energy and inspiration. A delightful piece.

- Benzene Dreams by Sarah Schofield (Afterword by Prof. Robert Stickgold). A potentially dangerous commercialisation of the techniques we witnessed in Adam Marek’s story, ‘Benzene Dreams’ tells us about Phil, a computer programmer who’s developed a new app called DreamSolve, which has the power to reinforce customer preferences or behaviours by learning and manipulating patterns of memory during sleep. Both big business and government are in a fiendish hurry to get their hands on DreamSolve, only there seems to be a problem – Phil won’t be bought. ‘You’re a wholly moral being, Philip, look at you. It’s adorable and terrifying all at the same time,’ says Diane, left-leaning government executive and supposedly the good guy. Phil soon learns that in this kind of race for primacy, no one is the good guy, and he is powerless. Schofield manages to make a chilling story very funny. I hope Phil gets his dog.

- Counting Sheep by Andy Hedgecock (Afterword by Dr Simon Kyle). ‘Fay flicked through sleep habit-tracker diagrams with their colourful spikes, spindles and histograms, explained the intelligent alarm clock function and demonstrated the sleep deficit indicators. “You put your phone under your pillow and it records tossing and turning, checks if you snore or talk in your sleep, and works out the best time to wake you with music, birdsong or whatever you like.”‘ A bunch of sociology lecturers at a FE college are encouraged to utilize the Dormouse app to regularise their sleep habits and up performance. Linden, scared of losing his job, complies with the guidelines. Lea is also scared of losing her job but is less prepared to put up with management bullshit. A shot across the bows from a writer who has clearly experienced this kind of corporate newspeak first hand and is rightfully angry. Linden is losing it – Hedgecock seems to be showing us a vision of what life might be like if the sleep app in ‘Benzene Dreams’ became a reality. I’m totally with Lea. Also contains Thea Gilmore reference. If this story doesn’t get you riled up you’re clearly already a pod person.

- Thunder Cracks by Zoe Gilbert (Afterword by Dr Paul Reading). ‘Now at thirteen years old, she is apprenticed to her father at the High Farm, where he makes workers of the wild horses and knocks the farm-born ones into good shape. Not the son he wanted but his eldest child, and he has no inkling how hard she has to try not to run away from those beasts, to be still when she looks at their rolling eyes, their twitching shoulders, She cannot harness their might, the way her father does.’ ‘Thunder Cracks’ feels a little like Whale Rider, only with horses. We are in an agrarian past, or possibly future. Madden is being schooled by her father to take over his work when he becomes too old to do it himself. Is it the storm that has caused Madden’s sleepwalking, or is she the emissary of forces beyond her control? Zoe Gilbert’s story, with its affecting poetry, its timeless setting, its stark illustration of how myth, magic and people are bound to a landscape, is easily my favourite of this anthology so far, at least partly because it seems so determined to take the original brief as inspiration only, to go its own wild way. I love it intensely.

- The Night Husband by Lisa Tuttle (Afterword by Stephanie Romiszewski), ‘A fantasy played out in my mind as I lay awake at home that night. Dr Bekar’s astonishment would lead to a more in-depth study which, although tedious, I must allow in the interests of science. Papers would be written, and I would be invited to appear at scientific conferences, and even on television. Others like me might come forward – how misunderstood we had been! – at last, our suffering was not in vain. Dr Bekar would write a book, and there would be a documentary made about my life, maybe even a docudrama, something like that one starring Robin Williams – Awakenings.’ A woman is plagued by sleep problems that started in childhood. She turns to a sleep clinician for advice, yet ends up finding answers much closer to home. This story has an intriguing premise, but for me it wore its research a little too openly on its sleeve. I think Tuttle would have been far better to dump the sleep lab stuff entirely and write more about the characters and their personal problems. To be honest, I’m coming to believe this is an issue that may be built into this particular format by default. Writing fiction is a intensely private process. There is a danger that having one’s research sources physically present in the form of a scientific collaborator might actively interfere with that. I can see myself writing more about this problem in my summing-up.

- Narcolepsy by Deborah Levy (Afterword by Prof. Adam Zeman). ‘He reaches for a packet of chocolate and marshmallow biscuits called Wagon Wheels and unwraps the foil as he speaks.’ Why not: ‘He reaches for a packet of Wagon Wheels’? Is this story aimed at people from Mars, or is Levy simply afraid of being seen dropping brand names a la Stephen King? (I ate my first Wagon Wheel more than forty years ago, at my grandma’s caff in Nottingham. These things ain’t new.) The wagon wheels (lower case) reappear later on in the story so I guess this might count as a kind of oblique foreshadowing. Oh, and do look out for what Gayatri says to the flower seller about Ilya Kabakov – priceless. Reads like Rachel Cusk – in fact, this story brings back to me all the reasons I wrote this blog post. Oh, I get it, I get it, but this kind of writing makes me so tired. Which is probably appropriate, given the subject matter. I’m guessing that the story is an extended poetic metaphor created to mimic the ‘waking dreams’ of narcoleptics, and, my appalling sarcasm aside, my writing self admires it tremendously, even if only for the fact that it shoots the brief in the head and keeps on running.

- Voice Marks by Claire Dean (Afterword by Prof. Manuel Shabus). When we reached a particular gritstone crag, Dad always stopped and said, he’s still in there. This sleeping knight wasn’t one of Arthur’s army, Dad said he was from another time. Once, I asked him what the name was for the bright orange rings that spattered the stone. They’re voice marks, he said – the marks his voice leaves when he shouts out. Whenever I asked after that he said lichen, only lichen.’ A beautiful, resonant story about memory and loss, and how the names and faces of the dead are returned to us as we sleep. There is a whole novel in these couple of thousand words. A lovely piece of work, up there with the Gilbert for me.

- Trees in the Wood by Lisa Blower (Afterword by Prof Ed Watkins). ‘This leaves me in the kitchen with the twins, Margot and Henry, who have just turned five and are still in their school uniforms squabbling over jigsaw pieces under the kitchen table where they also now like to eat. I have told Mia that I don’t agree with them eating off the floor like dogs, but she says at least they’re eating and it keeps them quiet and I spot a few rubbery-looking pasta twirls on the floor and a dollop of what looks like hardened ketchup.’ Laura lives alone. She hasn’t been able to sleep since the death of her mother. She’s spending the night at Mia’s house on the advice of her doctor, that she should undergo a course of ‘sleeplessness with someone you trust’. Mia is a palliative care nurse with five-year-old twins, a teenage daughter, and a never-there husband. She’s completely exhausted. The two women share an evening. From between the cracks, secrets emerge. The details and textures of the women’s lives are utterly different – and yet there is something that each can give the other. An emotionally draining, hard-hitting story with an unexpectedly positive outcome. Brilliantly written.

- In the Jungle, The Mighty Jungle by Ian Watson (Afterword by Dr Thomas Wehr), ‘Our toxins quickly taught predators to ignore us. I can kill a lion who only touches me, sniffing. We can also induce a numbness that is more like inattention. Halfmoonlight striping darkbark branches bushing leaves. Does Du-du wear a thing upon Du-du’s head? Hard to see, hard to know.’ Alien entities communicate with prehistoric humans by entering their dream-space. There is the unspoken assumption that these aliens may have been the ‘missing link’ in human development. A curious, and curiously attractive story, experimental and lyrical at the same time, with a backward nod to the science fiction of the 1970s New Wave.

- A Careless Quiet by Annie Clarkson (Afterword by Dr Paul Reading). ‘I tried to list in my head any symptoms I could have noticed, all those instances when you dropped something, or stumbled or fell, or shook a little, or couldn’t keep up, or when your foot went to sleep that time a few months ago and the sleeping in the day and the dreams. I didn’t know what was just age or tiredness or coincidence, or something I could have picked out from everything else, and said, ‘Something is not right here, Carl, let’s get this checked out.” A married couple experience changes in their life as their daughters grow up and they approach retirement. But Carl is suffering from strange dreams. He’s talking to himself in his sleep, and striking out at people who aren’t there. ‘A Careless Quiet’ is sensitively written but it reads more like a piece of life writing and there’s no real story here. We guess the ending long before it arrives.

- The Raveled Sleeve of Care by Adam Roberts (Afterword by Dr Penelope A. Lewis). ‘A word here as to his appearance: I would not have cast him, were i filming a melodrama about a German doctor. He did not look the part: no wire-framed spectacles, no kettle-shiny bald forehead, no agitated precision of movement.’ Flicking over to see what was on the Horror Channel last night, I came in midway through a movie called Outpost: Black Sun – ‘a German scientist by the name of Klausener is working on a terrifying new technology that will create an immortal Nazi army’ – which seemed to consist mainly of Jeff from Coupling grappling with a zombified Eva Braun inside some sort of secret bunker. I switched off, immersing myself instead in this weirdly similar but markedly better written story by Adam Roberts, in which the allusions are clever and literary and the humour is wholly intentional. The plot is simple: a French Nobel laureate makes the acquaintance of a mad German doctor who is working on the ultimate weapon – sleeplessness. He is persuaded by some equally dodgy Americans to pursue the Herr Doktor out to his secret compound in Argentina. ‘There was a single image, a portrait photograph of exactly the person you would expect to find in Schlechterschlaf’s study.’ There’s fabulous stuff like this all the way through. The story is wonderfully, boisterously insane, and exquisitely written. I loved every moment. And who else but Adam Roberts is going to call his Nazi villian Doctor Badsleep?

There are some outstanding stories in this anthology – I would single out the Gilbert, the Dean, the Blower, the Roberts and yes, the Levy for particular mention. As with any themed anthology, there is a tendency towards repetitiveness, a problem I think has been particularly exacerbated by the presence of such detailed scientific guidelines. The number of stories here featuring sleep labs, for example, is far higher than what would normally occur. Spindles presents us with a conundrum: it is an anthology that explores its subject matter intensively and in depth. It is also an anthology that presents, in places, a curious uniformity of approach. It will be noted that the stories that impressed me most were those that scampered, like recalcitrant schoolchildren, away from the brief.

I must also admit to having doubts about the overall wisdom of Comma’s ‘science into fiction’ concept. From the outside, the idea always seemed attractively intriguing. Now, having experienced it in close up, I am forced to conclude that this particular approach means that the stories are forever in danger of seeming merely like illustrations for the scientific afterwords. ‘Time to separate the science from the fiction,’ says Professor Robert Stickgold as he kicks off his afterword to Sarah Schofield’s story. You can almost hear him rubbing his hands together in his eagerness to get started on the dismantlement process. Sadly I couldn’t disagree more. By this point I was beginning to feel that these afterwords were having much the same effect as the electric light in Sara Maitland’s story: deadening the natural responses, destroying the secret rhythms of a mysterious and essential process.

I must stress that tolerance for such disruption may vary, and there will no doubt be many readers who relish the opportunity to get up close and personal with the scientific documents in the case. For these people, reading Spindles will provide an enthralling journey. Yet the ineluctable fact is, what scientists do and what writers do are two rather different things. That writers – and especially writers of science fiction – can, do and maybe even should draw upon the work of scientists in finding inspiration, direction, and a sturdy armature for their fiction is not in question. But to have the blinding interrogation lamp of fact shone directly – and so immediately – upon the fruits of their labours has had, for me at least, a seriously deleterious effect.

‘Like being shown a magic trick, and then having some other c**t walk out onstage immediately afterwards to show you how it was done?’ Chris suggested, when I was telling him about this. Yes, exactly like that.

And yet. It is impossible not to admire what Comma are doing here, and any project that innovates so intelligently is to be applauded. And so I would commend you to read this book. Immerse yourself in its contents and find out for yourself how you feel about them. I would expect science fiction readers and writers especially to come away invigorated and most likely inspired by the experience.

[DISCLAIMER: I received a review copy of this anthology direct from the publisher.]

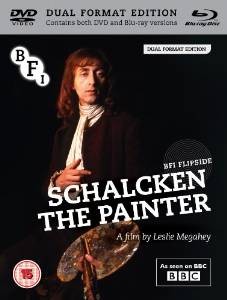

Schalcken the Painter, based upon an 1839 short story by Sheridan Le Fanu, is an extraordinary gem of a film that amply proves the power of the classic ghost story to shock and haunt.

Schalcken the Painter, based upon an 1839 short story by Sheridan Le Fanu, is an extraordinary gem of a film that amply proves the power of the classic ghost story to shock and haunt.

The DVD, recently reissued by the BFI, was given to me by Chris as a gift this Christmas. I’d never heard of the film before, though Chris remembers it from when it originally aired, as part of the BBC’s Omnibus series, appropriately enough at Christmas in 1979.

The story is a simple one: Godfried Schalcken (who is real, by the way – Le Fanu’s story doubles as an insightful commentary on his art) is apprenticed to the master painter Gerrit Dou in the Dutch town of Leiden. Schalcken is fiercely talented, but penniless. When he falls in love with Dou’s niece, Rose, he has little hope that they’ll be allowed to marry, a prospect that is entirely dashed when Dou effectively sells Rose to the enigmatic Mijnhir Vanderhausen of Rotterdam. Dou is uneasy about the contract, especially since he knows nothing about the mysterious suitor, nor has even seen his face, but when faced with the sheer splendour of Vanderhausen’s riches, he finds he cannot refuse.

When it is revealed to Rose that her future husband is ugly to the point of deformation, she begs Schalcken to run away with her. He refuses, pleading poverty – a moment that shocked me back to the fateful conversation between Natasha and Rudin in Turgenev’s Rudin – a decision which is to haunt him for the rest of his life.

Schalcken makes some desultory efforts to find Rose, but when these fail he is quick to seek solace in the tavern and in the brothel – also in his newly found fame as an artist, which is increasing rapidly. He is given one chance to redeem himself – and fails miserably. Dou never quite gets over the devil’s bargain he has made either, and goes to his grave still in agony over the unknown fate of his niece. Alone in the church after the funeral, Schalcken is finally granted the answers he has sought for so long – and wishes he hadn’t been.

The form the film takes is a gloriously simple recitation (by Charles Gray) of Le Fanu’s text, with the sparse dialogue spoken by the actors in a deliberately studied manner. The cinematic art that accompanies the words is incandescent. Every frame echoes a Dutch painting – the magisterial still-lifes, portraits and vanitases of Vermeer and van Hoogstraaten are referenced both directly and indirectly, to include extraordinary tableaux vivants as Dou and Schalcken clothe and arrange their models in scenes of allegory. The technical skill in achieving the colour and ambience of these paintings – the effect is sometimes so striking as to be uncanny – must have been considerable.

The moment of quiet horror when Vanderhausen’s visage is first revealed is sensational, reminding me of the equally pivotal and terrifying moment in Lynch’s Lost Highway when Fred turns over in bed and sees not the face of his wife looking back at him.

Le Fanu’s narrative accomplishes a tremendous amount in a relatively few pages. Fictions inspired by real works of art are always intriguing. That ‘Strange Episode in the Life of Schalcken the Painter’ manages to combine its percipient art criticism with an equally sharp critique of the position of women in Dutch society at the time makes it all the more compelling. Leslie Megahey’s film brings the text to glowing life in a manner that will amaze and delight anyone interested in art, or horror, and hopefully both. Very highly recommended.

My first encounter with David Bowie’s music came in 1975, when my brother and I purchased the single of ‘Space Oddity’ with our joint pocket money. My brother was seven, I was nine. We had this thing where we would sing and act out the lyrics. He was always Major Tom. I was Ground Control, and the background narrator. The helmet was a washing up bowl. We played the song endlessly. It was a game for us, a sort of party piece we would perform for our parents (who I’m sure became tired of it far more quickly than they let on).

It was something else too, though. From a very young age, I was obsessed with song lyrics (Middle of the Road’s ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’, which I thought was about a baby bird who had lost its mother, used to fill me with horror even as I enjoyed singing along to it) and the story told by Bowie’s song was a source of dread and wonderment to me. I know there are theories that the lyrics are actually code for taking drugs (aren’t all song lyrics?) but for me it was always simply about this astronaut, this internationally feted yet infinitely lonely man who was left floating in space, knowing he was doomed to die and yet was somehow OK with that. ‘And I think my spaceship knows which way to go’ – the line seemed unutterably sad to me.

I never spoke of these feelings. The song still seems both heroic, and unutterably sad.

I didn’t think much about David Bowie after that until the early eighties, when someone – I can’t for the life of me remember who it was – played me ‘Life on Mars’ as part of a compilation tape they’d made (remember those?) and that song has remained part of my personal lexicon ever since. Something about the chord changes, the aching swings from major to minor, and of course those lyrics. For me, the lyrics seemed to sum up everything about the nineteen eighties, even though I could never have said precisely what they meant. If I happened to hear the song playing on the radio I’d stop what I was doing to listen. When I hear it now, it seems to speak of a past I know we can never recapture.

I had a 12″ single of the German version of ‘Heroes’. My mum found it for me in our local record store. Even now when I think of that song, it’s the German lyrics I think of first.

Chris and I were talking about Bowie only last week, when we were driving back from doing the weekly shop and I was telling Chris about a glorious ranty send-up I’d heard somewhere or other, of the lyrics to ‘Starman’. (‘He’s come all this way, he has the power to cure global warming and cancer but what comes top of his list of priorities? Let the children boogie.’) Although I was never anything more than the most casual Bowie fan, when I turned on the radio first thing this morning and heard the news of his death I found myself harbouring the fleeting hope that it was all a hoax. David Bowie was one of those artists who seem timeless, who we come to think of as almost immortal. Then they are gone, and the world is, somehow, just a little bit changed.

I remember saying at the end of 2014 that I was dissatisfied with what I’d read. Not with the books, or not with all of them by any means – when I look back at my books-read list for 2014 and see it included Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, Joyce Carol Oates’s The Accursed and Paul Park’s All Those Vanished Engines, I feel an instant wave of nostalgia for those sublime moments of discovery – but with my own disjointed approach to the reading year. Just a bunch of books, basically, and no order, system or overall plan to distinguish my choices.

Not that one should feel obligated to have a plan – choosing what to read next can be a decision as personal, random and fortuitous as the reader’s heart desires – but I like the idea of being headed somewhere, of ending the year with the sense that I have moved forward as a reader, that my default choices have been challenged in some way, that my reading has given me new ideas about where I want to go as a writer. When I happened to come across Jeff VanderMeer’s Epic List of Favourite Books Read in 2015, I was struck by its sense of cohesion, the sense that these were books you could return to again and again for new insights. They made sense as a group, somehow. Also they seemed so refreshingly, blessedly different from so many of the books on most of the ‘Year’s Best’ lists that are currently doing the rounds.

In 2015, as in 2014, I don’t feel I’ve achieved anything like that. I’ve read some astounding books and some indifferent books and some really rather bad books. I’ve read books that have surprised me and books that have disappointed me and books that have inspired me. On the whole though, I feel that my reading experience has been circumscribed by its randomness. I think at least part of the problem – maybe even the larger part – is the pressure one feels these days, as a reader, to be current. To be up with what’s coming out and down with the various literary prize shortlists. To have what passes for a relevant opinion – on a bunch of books that just happen to have been published in a given year.

I’ve come to believe that these pressures have been working against what I want to do, what I need to gain from reading, as a reader and as a writer. Awards shortlists may be lots of fun to dissect, but as arbiters of anything other than themselves, they are confining. Which is why I want to pay less active critical attention to them in 2016. Unless an awards shortlist seems particularly relevant to my interests, I won’t be rushing to read it or even comment on it.

I’ve seen various book bloggers talking recently about an ongoing online community project called the Classics Club – members select a personal list of 50 books, to be read and blogged about over the course of five years. The only rule is that all books selected should be at least twenty-five years old – other than that, it’s completely up to individual members how they choose books, and which books they choose. I think it’s a fascinating idea – once you’re freed from the need for everything you read to be ‘new and upcoming’, your choices are almost bound to be more challenging and, in a strange way, more personal. Take a look at David Hebblethwaite’s newly complied list and you’ll see what I mean.

Thinking around these ideas, I came up with one of my own that feels even more right for me at the moment – My Year of Reading Weird 2016. There are no hard and fast rules – I’m too good at finding excuses to break them. I’m not banning myself from reading 2016 books either – but I do want to try and ensure that a good proportion of the novels I read this year are novels that were published before this year, to include at least a couple that really are ‘classics’, published a century ago or more.

The overall aim of the challenge? To increase my knowledge of weird and horror fiction. I’ve always thought of horror as the area of speculative fiction I understand best, and yet I know I’ve been neglecting it somewhat in recent years. There are new writers and books I’m very aware I’ve not read yet – as well as the many, many gaps in my knowledge of historical and classic weird. My goal is to make a move towards putting that right, and I think I’ll be gaining a lot as a reader and as a writer in the process.

It goes without saying that I’ll be looking for the weird in some unexpected places. While I might be rereading The Tales of Hoffmann, I might also be finally getting around to Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones, which has to count as horror, more than anything else. I definitely want to include more literature in translation, and I’ll probably be including some films and individual short stories along with the novels. Weird also might simply refer to the way a book is written – the form a book takes is often as interesting to me as its content, if not more so.

I’m hoping to blog as many of my weird and horror reads as I possibly can, providing not so much book reviews as a kind of running commentary on my experience. I might, occasionally, get ranty.

And you know, I’m looking forward to this already.