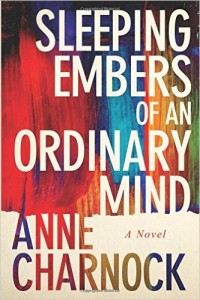

Regular readers of this blog will know how much I’ve enjoyed and admired Anne Charnock’s first two novels, the Philip K. Dick Award- and Kitschies-shortlisted A Calculated Life, and Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind, which was published towards the end of last year. I found A Calculated Life to be one of the most fascinating and imaginative explorations of the post-human condition that I’ve yet read, and in Sleeping Embers especially, with its interwoven narrative threads and themes of art and memory, I sensed that Anne and I shared some common interests as writers. I was therefore delighted when Anne invited me to take part in an online ‘conversation’, the aim being to examine and hopefully illuminate some hidden aspects of what we write, and how we approach our chosen subject matter. Neither an interview nor a traditional Q&A, the conversation format allowed for a more free-flowing discussion, more approximate to what you might expect in a live panel event. As we both hoped at the outset, it threw up some unexpected insights. That it was a great pleasure to ‘talk’ to Anne should go without saying.

ANNE: Recently I read Stephen King’s On Writing and although he gives great![ACharnockPortrait copy [458685]](http://www.ninaallan.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ACharnockPortrait-copy-458685-236x300.jpg) advice throughout, I was curious about one of his comments on the subject of theme. He feels that the theme of a novel is something that emerges in the first draft or after the first draft, and can then be enhanced in subsequent reworking. But for me the theme, or concept, comes first, before I start outlining and plotting a piece of fiction. How do you view the importance of theme? Does it vary from one writing project to another?

advice throughout, I was curious about one of his comments on the subject of theme. He feels that the theme of a novel is something that emerges in the first draft or after the first draft, and can then be enhanced in subsequent reworking. But for me the theme, or concept, comes first, before I start outlining and plotting a piece of fiction. How do you view the importance of theme? Does it vary from one writing project to another?

NINA: I love Stephen King’s On Writing. I’ve read it several times, just for the pleasure of King’s voice, and it’s the one book I recommend unequivocally when people ask me if ‘how to’ guides for writers are any good. As a new writer, what On Writing offered me, most of all, was the permission to do things my way. Many of the writing guides I’d read previously – and yes, I did love reading them – seemed very keen on pre-planning, on writing chapter summaries and on knowing exactly what was going to happen before you started. This made me feel nervous because I instinctively felt that those methods weren’t going to work for me. What King seemed to be saying was ‘screw that – there are no rules. Do what feels right’. It was like a breath of fresh air.

I don’t remember King’s exact words on theme versus plot – but what I do know is that for me, plot has always been the element of narrative I try to think about least consciously, particularly when I’m making a start on a new piece of work. I’ve always started with character – or to put it more precisely, with a particular character in a particular situation. I name my character – character names are very important to me as they seem to form a nest of associations all by themselves – and I think about what might be worrying them, what problems they face, how they might react, who they might know. Theme tends to arise naturally from these thoughts, and from the situation. Theme is important to me, as an anchor – as the box everything fits inside, if you like. Plot is something I have to trust will attach itself to the theme as I go along. The more I write the more the plot begins to define itself. Often I won’t know how a story is going to work itself out until I’m at least half way through. But this is why second drafts are so important to my working process. When I start my second draft, I begin writing the book again from the beginning, essentially – only this time I know where it’s going, I know what the plot entails, I know how things end. Which means I can foreground certain details, strengthen certain narrative threads. I love second drafts! They are so much less scary.

How about your drafting process? Do you like to edit on the page, refining the narrative organically as you progress, or do you write right to the end and then second-draft everything from the beginning?

ANNE: Like you, Nina, I let the narrative unfold during the drafting process. This feels more natural to me. And because I ‘feel my way’ with the narrative, I now find I’m attracted to writing in present tense, as though I’m experiencing events alongside my characters. I edit at a sentence level as I go along—which can be very slow! However, this does mean that when I reach the end of the manuscript I don’t need to redraft from the beginning. I might add a scene or move a scene. But I’m mainly fine-tuning the characters and dialogue, making ‘fixes’ to the narrative, looking for inconsistencies, fact-checking and so on.

Throughout the drafting, I fill in a spreadsheet that summarises the narrative developments in each chapter. Sometimes the narrative develops in such a way that I know I’ll need to make adjustments in earlier chapters. I add notes on the spreadsheet to remind myself to make specific changes in the next draft. And I do enjoy this process of refinement.

In my current writing project, I’ve taken a different approach. I’m first-drafting this novel with less on-the-go editing. I’m conscious of my deadline with this project so I feel more comfortable pushing forward. I’m still keeping a spreadsheet of the narrative development, and this is really important because this novel has a highly fragmented structure. I expect I’ll write additional fragments when I’ve finished the first full draft. With each of my main characters in this novel, I’m interested in the specific events in his or her back-story that has moulded their character: nurture over nature, I suppose.

I know from your own writing, Nina, that you’re interested in fragmentation. I’d like to know what draws you to this type of structure.

NINA: It’s going to be interesting for you to see how the quicker-first-draft method suits you! I imagine your spreadsheets to be a little like Nabokov’s famous index cards – a way of examining characters and events in isolation from their story. A fascinating approach.

NINA: It’s going to be interesting for you to see how the quicker-first-draft method suits you! I imagine your spreadsheets to be a little like Nabokov’s famous index cards – a way of examining characters and events in isolation from their story. A fascinating approach.

I first encountered fragmented narratives through the work of Keith Roberts and his great novel Pavane, also Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic. This would have been in my mid-teens, when I was reading a lot of science fiction pretty indiscriminately. Most of the stuff I read then – Heinlein, Silverberg, Asimov, Pohl – has fallen by the wayside for me, but both Pavane and Roadside Picnic, and their authors, remain touchstone influences. Thinking about them now, I realise that when I first read these novels I didn’t think of them as ‘fragmented narratives’, I simply accepted this method of telling a story as something that was natural and intrinsic to those books, and got on with enjoying them. And yet they made a powerful impact – something about the thrill of discovery, the way my own imagination played a vital role in linking everything together. I wouldn’t have analysed it that way at the time, but I think I found something very satisfying in the idea of the reader interacting with the writer to create a complete picture.

Fragmented narratives are often described as being complex, and of course they can be, but I happen to believe that large numbers of readers actively enjoy the element of mental participation this approach encourages. Novels such as David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas and Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven have found immense popular appeal. Similarly, movies such as Paul Haggis’s Crash and Alejandro Inarritu’s Babel, which both involve intricately interlinking storylines, have enjoyed Oscar-winning success. I think readers can actually tolerate narrative complexity to a far greater degree than the publishing industry sometimes gives them credit for. One of the reasons crime fiction is so popular is because readers feel directly involved with what’s happening on the page, and I think the clue-hunting aspect of fragmented narratives performs this same function.

I loved the three-stranded structure you used in Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind. Did the experience gained in writing this novel help you in planning this next book? You say the structure of this new novel is ‘highly fragmented’ – can you tell me how it differs from the construction of Sleeping Embers?

ANNE: Thanks, Nina. I like the comparison you make with crime fiction! I do have fun introducing clues and connections when I’m drafting a fragmented novel. I’ve always liked writers who play around with structure. So the novels that come to mind are Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas and Ghostwritten, Michael Cunningham’s The Hours and Specimen Days, Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, Georges Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual, Adam Robert’s The Thing Itself, Sara Taylor’s The Shore, Louisa Hall’s Speak. When I start to list them—and I could list so many more—I begin to see how popular this form is among writers.

My work-in-progress already has a title—Dreams Before the Start of Time. I started drafting this novel some time ago, but I broke off to begin Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind. So the influence happened in reverse; the fragmented structure of Dreams Before encouraged me to tackle Sleeping Embers as a novel set in three time periods—Renaissance, current day and twenty-second century—with the narrative oscillating between the three settings.

In contrast, Dreams Before the Start of Time is linear, moving forward from the very near future to a hundred years from now, and it follows the lives of two women who are close friends. A handful of chapters are written from their points of view, but most are told from the points of view of characters who are connected either closely or tangentially to the two women.

I don’t regard this new novel as a sequel, but one of my main characters is Toni Monroe who is a character in Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind. I still felt a strong connection to Toni, and her age fitted neatly with the setting of my new novel. This brings me on to say that one of my quests in writing speculative fiction is to create characters who engage the reader on an emotional level. I don’t want the reader to envisage the future in a detached way. For me, an exemplar novel—one that’s compelling in an emotional sense—is Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. I wondered if you could identify your own writing quest, and if there’s a single novel that would indicate your goal.

NINA: I love the sound of Dreams Before the Start of Time, and especially the idea of Toni as a continuing character. You mention David Mitchell here – a writer who is now well known for extending the life of his characters beyond the frame of a single novel – and indeed this is something I enjoy doing myself. I first experimented with recurring characters in my story cycle The Silver Wind, where the same characters crop up time and again, although not always in the same roles. (Stephen King has a lot of fun with a similar idea in his twinned novels Desperation and The Regulators, which are favourites for me amongst his work.) I’m currently working on a story that features a character from my first collection, A Thread of Truth, a character I hope to write about at greater length in a future novel.

As you say, it’s difficult to let go of these people sometimes!

Never Let Me Go is a fascinating choice for your ‘quest’ novel – humane and chilling and very much in the tradition of British speculative fiction – I’m thinking of novels like D. G. Compton’s The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe, a key novel of the SF New Wave which examines anxieties about future technological development through a very human lens.

I do like this idea of having a writing quest! I suppose if I had to pin down what it is that I’m going after with my writing, it would be the preservation of memories, of moments in time, and how memory is always this peculiar and sometimes problematic blend of objective ‘truth’ and subjective worldview, which is by its nature partial, and often unreliable. I am in love with the weirdness at the heart of mimesis, and the writer who encapsulates this in her writing most perfectly of all for me is Iris Murdoch. There is something exalted about her work, a sense of heightened reality that shines a light on ordinary objects and occurrences and reveals their hidden magic – and madness. If I had to choose one of her novels to take with me to a desert island it would be The Book and the Brotherhood, which I’ve read four times already and could start reading again tomorrow with equal enjoyment.

I would pair that novel with works like The Course of the Heart by M. John Harrison and The Girl in the Swing by Richard Adams as examples of British Weird, a tradition that I feel is central to my own practice and allegiance. Do you think of yourself as being a particularly British writer? Or do you see yourself as having more in common with the new internationalism that is beginning to characterise contemporary science fiction?

ANNE: I suppose I do think of myself as a British writer. My speculative fiction fits pretty neatly with your comment on SF New Wave. But I’m not so keen on pinning these things down—I don’t wish to feel any obligation to carrying on doing what I’ve done before, if you see what I mean.

I’m pleased you mention Iris Murdoch. I’m also a fan of Doris Lessing’s mainstream novels including The Fifth Child and its sequel Ben in the World. These are disorientating and distressing reads, almost fantastical, because as the narratives unfold you don’t know what or who to believe. It’s rather like the slipperiness of memory that you refer to. I feel these two novels anticipated Lionel Shriver’s novel, We Need to Talk about Kevin. We can’t seem to nail the truth in these novels.

I’m pleased you mention Iris Murdoch. I’m also a fan of Doris Lessing’s mainstream novels including The Fifth Child and its sequel Ben in the World. These are disorientating and distressing reads, almost fantastical, because as the narratives unfold you don’t know what or who to believe. It’s rather like the slipperiness of memory that you refer to. I feel these two novels anticipated Lionel Shriver’s novel, We Need to Talk about Kevin. We can’t seem to nail the truth in these novels.

So, you’ve chosen your books for the desert island! I played this game at my local book group’s Christmas party. I chose Michael Cunningham’s short novel, The Hours. I do regard this novel as a perfect example of a fragmented structure, linked as it is to Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (I’d need to take her novel too!). I’d spend my time on the desert island working out all the connections between the two novels, and lapping up Cunningham’s beautiful writing style.

I know some writers don’t like to talk about their work in progress, but can you tell me about the novel you’ve recently completed, and any other fiction in the pipeline?

NINA: That’s an interesting point you make about the way Doris Lessing’s ‘Ben’ novels anticipate Shriver’s Kevin and I agree absolutely. An aspect of Lessing’s career that is not discussed anywhere near enough either within the mainstream or in genre circles is her lifelong fascination with speculative ideas. There are the two novels you mention, which as you say teeter on the brink of the fantastic, her Shikasta series, Briefing for a Descent into Hell, The Memoirs of a Survivor (both of which are briefly discussed in my own novel The Race) and also later works such as The Cleftand Mara and Dan. I’ve noticed an unwillingness within genre communities to admit the importance of writers like Lessing and of course Margaret Atwood, to dismiss them as dabblers or ‘tourists’, an attitude which is frankly ridiculous when it could be argued that half of Lessing’s output is speculative, when Atwood has not only produced a novel – The Handmaid’s Tale – which will stand as one of the core works of the SF genre for decades to come, but has also, with the Maddadam trilogy and now The Heart Goes Last, dedicated the whole of the past decade more or less exclusively to writing science fiction. I could speculate for a long time upon the reasons for this kind of inverse genre snobbery, but suffice it to say that I think it needs to stop! Science fiction has much to draw from the mainstream in terms of depth and craft, just as mimetic literature is finding itself reinvigorated by speculative ideas – ideas a lot of mainstream writers wouldn’t have been seen dead trying out even two decades ago. Literature is reactive as well as proactive. As writers, we see something someone else is doing and immediately begin to consider how we might bring something like it into our own work. We’re magpies! Reading widely – and letting that reading have its way with us – is a large part of how we learn to advance as writers.

My second novel is called The Rift. It began as an alien abduction story, or something like that, but morphed into something different as I was writing. It’s the story of two sisters, Selena and Julie, who owing to unexplained circumstances have not seen one another for twenty years. When Julie unexpectedly returns, Selena is left feeling that the life she has lived since Julie’s disappearance has been a lie. It’s a novel about memory, and loss, but there is some weird alien stuff in there, too. The Rift is scheduled for publication in summer 2017. I’m currently in the early stages of thinking about my next book, which at the moment mainly consists of a file full of notes and a long list of books I need to read. I am, however, cautiously excited…

ANNE: On the subject of magpies, I agree! We advance by reading widely, and reacting to other writers’ work. Appropriation is a minor theme in Sleeping Embers—how all the arts are enriched and energized by revisiting the past, by borrowing from other art forms, and using other artists’ work as a springboard.

*

Well, Anne and I both agreed that this could have run and run, but we had to bring it to a close somewhere! For those of you planning to be at Eastercon, you can catch Anne in conversation for real on the Sunday at 4pm, this time with Matt Hill. They’ll be discussing the influence of Manchester on their writing, among many other things I’m sure. It’s bound to be a fascinating discussion. In the meantime, you can visit Anne’s blog here, and of course read her books!

Only a few weeks ago he had watched them all coming out of the Curzon at midnight from some horror film that the paper said involved jack hammers and acid. They were laughing. The girls with their hands in the back pockets of the men.

Only a few weeks ago he had watched them all coming out of the Curzon at midnight from some horror film that the paper said involved jack hammers and acid. They were laughing. The girls with their hands in the back pockets of the men.

![ACharnockPortrait copy [458685]](http://www.ninaallan.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ACharnockPortrait-copy-458685-236x300.jpg)