Admirers of Gordon Burn’s true crime writing and of his novels, which tie imagined characters and events to the real-world news cycle with such skill the joins are seamless, are sometimes surprised to discover that Burn also wrote frequently and with equal commitment about contemporary art. Think about it some more though and you’ll see how these two subjects, art and crime, which on the surface would appear to be actively in opposition to one another, form an occasionally uncanny alliance. Artists, like criminals, often stand on the fringes of consensus reality, and it has been said about more than one artist that if they had not found their vocation, their life might easily have unravelled in a darker direction.

More even than that, art will invariably tell us a lot about the society in which it was produced. Writing about art, like writing about crime, is a way of identifying and parsing who we are and where we live.

Reading Burn’s posthumously published collection of essays Sex and Violence, Death and Silence: Encounters with Recent Art (much of it over a seemingly interminable recent train journey to London) has left me so energised and so confounded by the brilliance of his writing and the acuity of his insights I’m finding it difficult, at the moment, to think about reading anything else. In his own introduction to the book, Burn writes about how ‘more than most British writers, I think, I am open to the experience of art as an influence on what I do. … I tend to look to shows, and art catalogues, rather than to mainstream publishing, for stimulation (direction, really) and ideas. I feel that visual artists are consistently ahead of most writers in sensing significant shifts in how we think and see.’

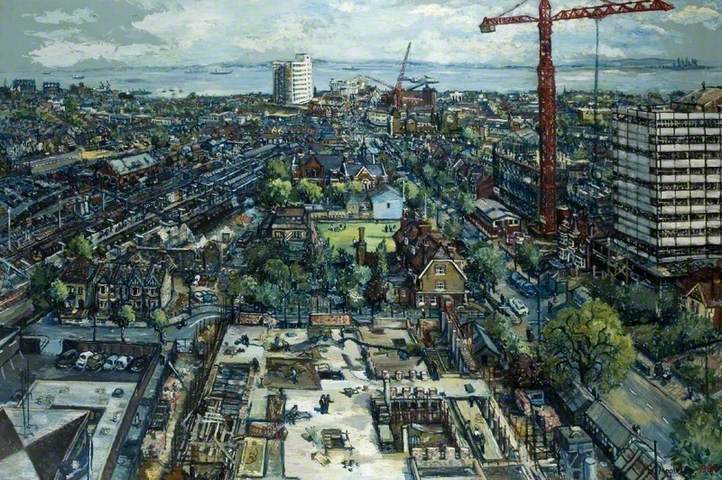

How could I not think of JG Ballard when I read that? The essays in the first part of the book, on Blake and Hockney (‘You can do an amazing lot without leaving the house,’ Hockney says. ‘Vermeer never left the house, and neither do I.’) and Bacon, are subconsciously reflective of that Ballardian moment, that Ballardian mindset and for me Burn’s writing on Patrick Caulfield, on Caulfield’s (literally) visionary relationship with London especially reads like a Polaroid snapshot of my own feelings about the city. I love Caulfield’s work: standing somewhat in the shadow of Hockney’s, it’s not been written about enough. Burn’s writing about Ian Hamilton Finlay’s trenchant opposition to the modern world is more nuanced and more open-ended than Jonathan Jones’s recent review of Finlay’s sculptures at Victoria Miro and carries deeper insights as a result. (I adore Jones because he knows so much, writes so well and unlike most broadsheet critics these days is prepared to take on the haters from both sides of the fence. His reviews are always a treat – very few on the books pages take such chances, which is a shame. But c’mon Jonesy, one star??)

Burn’s relationship with the YBAs, with what he calls ‘the Britart moment’ as filtered through his friendship and extended conversations with Damien Hirst will and should go down as some of the most engaged and empathetic commentary on the seamier side of Cool Britannia and the new conceptual installations of Hirst, Hume, Lucas, Whiteread, Emin, Landy, Wearing and the other artists whose work shaped the 1990s as much as it was shaped by them. Writing about Hirst, Burn finds a comparison with ‘writers such as Don DeLillo, Richard Powers and others, who have acknowledged the poetic lure of modern jargon from science, sports and Madison Avenue in their fiction. Hirst located an unlikely poetics in the boilerplate prose of the scientific paper and the pharmaceuticals catalogue, and in the disease- and death-tainted artefacts of the mortuary, the pharmacy and the lab.’ He might well have added ‘as well as the crime scene’. Once again, the Ballardian associations are so powerful that it seems almost absurd that the paths of these two writers didn’t cross. Burn interviewing Ballard – one of those significant moments of literary history that never happened. Maybe it’s inevitable that they never met, though: they both preferred the company of artists to that of other writers.

But it is in his essays on the ‘court artists’ commissioned to make drawings for news outlets during high-profile murder trials, and on the German artist Gregor Schneider especially, that Burn makes the closest connections between his most prominent areas of interest as a writer. He opens his chapter on Schneider by revisiting his own work on the West murders, Happy Like Murderers (readers of this volume will already know from the opening conversation between David Peace and Damien Hirst that the original cover for the West book was itself designed by Hirst) before bluntly stating that ‘it is well known that Gregor Schneider has a lifelong interest in scenes of crime. As a schoolboy he obsessively photographed a place in the woods where a female art student had been murdered.’ Burn draws a direct lineage from Schneider back to the post-WW1 German Expressionist painters Dix and Grosz, whose art is filled with traumatic images of wounding, suicide and murder, quoting Schneider as having said that he ‘would love to stop someone getting away one time, but I have never dared to yet. I’m one of those people who live double lives and go out into the park at night and sift through the litter bins and secretly take something home with me. I assume that there are others working at it and I will probably never meet the best ones.’

Is Schneider one of those artists who live dangerously close to the boundary, whose work veers away from self expression towards actual transgression? I’m not so sure of that. John Fowles made similarly outre comments in his diaries when he was writing The Collector and there is a hard line, actually, between art and murder. But in drawing the comparison, in placing certain images, shockingly, side by side (Schneider thinking about his art, Fred West’s obsessive preoccupation with DIY) Burn is showing us something difficult, and difficult to think about. He is showing us what we all – somewhere, somehow – might have within us.