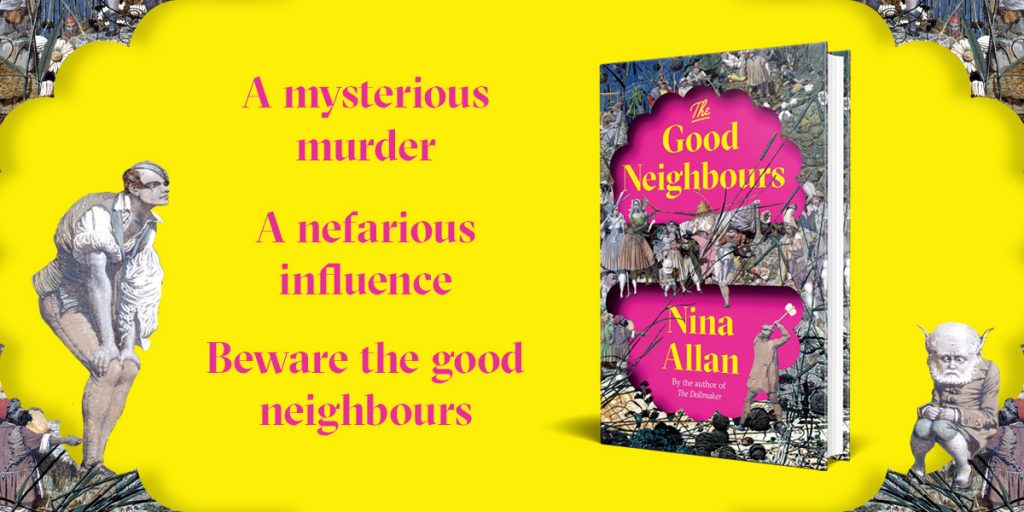

My new novel, Conquest, is published today.

Jonathan Thornton’s insightful and generous review at Fantasy Hive offers an eloquent analysis of its structure and intentions, while Steve Andrews brings his particular knowledge and engagement to our ‘interview-review‘ at Outlaw Bookseller. As always, I hope that readers both familiar with my work and entirely new to it will enjoy discovering their own reactions and responses to a book that was a long time in the making and is to an extent a personal commentary upon the last few years.

Conquest is a novel about truth and post-truth, the familiar made strange, communal crisis and personal epiphany. But on the day that sees the book pass from my hands into the hands of readers, I would like to reflect upon the theme that perhaps most of all provided its guiding inspiration. In one section of the novel, my private investigator Robin remembers how at the age of twelve she fell ill with pneumonia and as a result was absent from school and from her normal life for more than six weeks. Feeling weakened from the disease and with no one to talk to, she listens to Radio 3 for hours on end. This is where, for the first time, she hears the Goldberg Variations, and falls in love with the music of J. S. Bach.

The same thing happened to me, more or less, and I count those six weeks spent listening to music as some of the most formative in my cultural life, a period in which I was able to experience works that might not otherwise have crossed my path until much later. Where I was able to think, in privacy and without interruption, about what music meant, not only in terms of my own emotional reaction to it but in the abstract.

Unlike Robin, this was not when I first heard the Goldberg Variations. I came to know Bach through others of his compositions: through listening endlessly to the violin concertos and playing the flute sonatas, through singing in the B minor mass, a valuable and joyous apprenticeship that meant when I finally did come to know the Goldbergs, in my middle twenties, it felt like coming home.

One of the fringe benefits of my many years spent working in a music shop was the opportunity for listening. I was responsible for our whole stock of classical recordings, which meant I could buy in and test drive anything I wanted to. The effect was similar to being let loose in an enormous playground. One of the lessons I learned from all that listening was that recordings I initially considered my favourites could and often did cede their position to other performances, sometimes in the same day. That the point of studying different recordings is not simply to establish a hierarchy, fun though that can be, but to come to a deeper understanding of a piece of music through its various interpretations.

You would be surprised at the number of times you rub shoulders with Bach – through advertising, through film or game soundtracks, even through lift music – during the course of a single week. Without our consciously realising it, Bach reveals himself to us through an accumulation of encounters over many years, sure proof of his continuing ability to speak directly to millions of people across every conceivable divide of age or culture or background. Bach’s work deepens our relationship with the past, even as it informs our present. Through an intricate interweaving of sound and meaning that seems hardwired into all of us, Bach gives us faith in the future.

I have tried to convey something of Bach’s timeless and magical appeal in my writing of Conquest. I have not felt ready to write at length about music before now, precisely because the subject means so much to me, and also because it is difficult, for any writer, to add anything to what is already present in the music itself. In setting out to explore Robin’s world, and most especially Frank’s, I have found myself constantly in mental dialogue with those writers who have struggled with similar questions, and in so doing provided inspiration of their own. I hope I have added something to the conversation. I hope most of all that anyone reading Conquest who has for whatever reason persuaded themselves that Bach is not for them will throw aside their preconceptions and listen again.