Yesterday I had the great pleasure of taking part on an online symposium on the work of William Golding, organised by Arabella Currie and Bradley Osborne, under the aegis of the University of Exeter (nice to be back there, if only via Zoom!) This turned out to be one of the most inspiring and energising events I have yet taken part in, with engaging contributions from everyone involved and some excellent discussion. The artwork and storyboarding shown to us by Adam Gutch, who is developing an animated movie of The Inheritors, left us all feeling more than a little eager to see that project come to fruition. And the paper on the science fictional sensibility of Golding’s sea trilogy from poet and scholar William Stephenson was another highlight in a day that was all highlights. I had not realised Exeter boasts such a rich treasure trove of original Golding material, and the wonderful presentation from head of heritage collections Christine Faunch made me determined to visit the archive personally in the future.

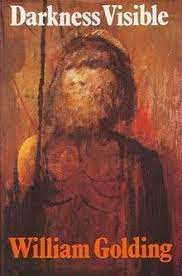

My own part in the proceedings came soon after lunch. You might remember how my interest in Golding was reignited by the Backlisted podcast’s discussion of The Inheritors last year, in particular the contributions from Una McCormack on Golding’s place in the history of British science fiction. It was a real joy to be able to carry on those discussions with Una in person during our joint presentation, ‘Beyond Gaia: Golding and Science Fiction’. Una gave a fascinating talk on how Golding kicks away the genre scaffolding and dives deep into the heart of speculative ideas, and I followed this up with my own short paper on what some have claimed to be Golding’s most enigmatic novel, Darkness Visible, the full text of which is below.

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to everyone involved in making our event such a success – organisers, speakers and audience – and here’s hoping we can someday meet again in person for more discussion and fruitful sharing of ideas.

*

Alien Country: William Golding’s Darkness Visible and the anatomy of the strange

In his review of Darkness Visible for the London Review of Books in 1979, the Oxford scholar and critic John Bayley summoned the spirit of Borges to describe Golding’s fiction:

“Borges has written that the writer is like a member of a primitive tribe who suddenly starts making unfamiliar noises and waving his arms about in strange new rituals. The others gather round to look. Often they get bored and wander off, but sometimes they become hypnotised, remain spellbound until the rite comes to an end, adopt it as a part of tribal behaviour.

A simple analogy, but it does fit some novelists and tale-tellers, preoccupied in the midst of us with their homespun magic. They are not modish, not part of any literary establishment. Nor is there anything of the showman about them: Dickens was a magician in another sense, the sense that goes with the melodrama and music hall, and tribal magicians are not creators as Dickens and Hardy were. Their appeal has something communal, as the Borges image suggests, and the shareability of a cult. America lacks this type of magician – the shamans there are grander, more worldly, more pretentious – and the German-style version of Hesse or Grass is too instinctively metaphysical, not homespun enough. Richard Hughes was one of Britain’s most effective local magicians; John Fowles has become one; William Golding has had the status a long time.”

We might choose to quibble with Borges’s use of the term ‘primitive tribe’; we might equally dispute Bayley’s summary dismissal of American and German novelists as purveyors of magic. What makes Bayley’s review of Darkness Visible interesting to me – aside from the fascination of reading a piece of criticism contemporaneous with the novel itself – is how closely it coincides with my own view of Golding as one of what I have come to think of as the maverick strain in British fiction: novelists who, though seldom regarded as such, reveal a secret stratum of the fantastic amidst a literary geology more commonly described in terms of its obsession with novels of social mores, its tendency towards mimesis.

When American critics talk about the genealogy of science fiction they present us with a lineage that begins with the pulp magazines of the 1920s, that pays homage to the holy trinity of Campbell, Asimov and Heinlein. Fantastic literature written earlier – or that does not accord with a set of fuzzy and increasingly spurious set of definitions – is too often dismissed as ‘proto-SF’ or ‘not really SF at all’. Long before I had ever heard the name of Hugo Gernsback, or had any inkling that science fiction was supposed to adhere to any specific set of arbitrary man-made criteria, I was beginning to discover for myself a more home-grown, or to echo John Bayley homespun genealogy of the fantastic that appeared to have grown up organically, not from any pre-determined magic spell but from the independent-minded, endlessly curious and – yes – maverick spirits of the writers themselves.

I didn’t know Beowulf then but I did know Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights and The Woman in White. I knew H. G. Wells and his Time Machine, Aldous Huxley and his Brave New World, John Wyndham and his Kraken. As I grew older and read more widely I was delighted to discover echoes and resonances of these elder gods in the work of George Orwell, Iris Murdoch, Rumer Godden, Mervyn Peake and JG Ballard, John Fowles, Doris Lessing and Christopher Priest. These writers, it seemed to me, offered me a view of my native landscape and cultural background that seemed to accord more closely with my imaginative experience than either American science fiction writers – mostly aliens! – or the British mainstream literary canon.

An early and immediately beloved discovery in this hierarchy of misfits was William Golding. I would not like to guess at the number of times I read Lord of the Flies between the ages of twelve and twenty – I can only say that the story horrified, bewitched and inspired me in equal measure. I quickly went on to read Pincher Martin, equally wondrous and, to use a Golding word, weird. I have not counted Golding’s uses of the word weird in Darkness Visible; perhaps I should have done, given that no other word seems as apt to describe it.

Darkness Visible is thought of by many as the most enigmatic of Golding’s novels, which is interesting, given that it is unarguably the most modern. Published in 1979, Golding actually began writing it in 1955. In its first, tentative incarnation it was actually a science fiction story entitled Here Be Monsters, set in the future amidst a landscape of accelerating nuclear proliferation. It is famously the one work of his he consistently refused to discuss. It tells the story of Matty, an orphan child who stumbles from a burning bomb site at the height of the London Blitz, Sophy Stanhope and her twin sister Toni, prodigiously intelligent yet morally adrift, and Sebastian Pedigree, a paedophile teacher who is both disparaged and sheltered by the institution that employs him. The action centres upon the town of Greenfield, a suburb of London situated on the fault-line of post-war austerity and modernising, multicultural Britain.

Matty’s origins and parentage are never discovered – his constantly misplaced surname is used to symbolise the mystery of his fiery origins. As he grows towards adulthood, the facial scarring he incurred as a result of the bombing is a constant visual reminder of his apartness. Yet Golding leaves no doubt that Matty’s essential separateness from his fellows runs much deeper than physical appearance.

Matty’s vision of the world is as a mysterious other, a realm in which good and evil fight for supremacy, symbolised for him in the perfect shining roundness of the spherical glass paperweight in the window of Goodchild’s Rare Books. When he becomes unwittingly drawn into the simmering conflict between Sebastian Pedigree and the school’s headmaster, the fallout is tragic, impacting itself not only on Matty’s immediate future but ultimately on the fate of every character in the novel.

By contrast, the Stanhope twins Toni and Sophy view the world through a lens of cynicism shading to nihilism, the fruits of parental neglect combined with an innate surfeit of self-awareness. Toni runs away from home at the age of sixteen, quickly becoming involved with a terrorist group perpetrating outrages in Europe and the Middle East. Sophy’s spiritual rebellion appears more subtle, yet its end results are scarcely less disastrous. In literary terms, Matty and the twins are opposing devices; the scarred outcast Matty touched by the divine, the preternatural physical beauty of the Stanhope twins standing in pointed contrast to their moral vacuity.

For me though, Golding resists such simplistic analysis, and Darkness Visible is infinitely more complex, more ambiguous. Matty is morally good, but he is not a freethinker. He ‘does not get the code’ and so his goodness is rather like that of Frankenstein’s Monster: an innate innocence that is also rigid, shaped by and subject to the rules and rhetoric of organised religion and with a similarly unexamined outcome. Sophy Stanhope is a symbol not of evil but of existential disenchantment. She struggles within the bonds of existence as it is, strains towards something greater, a larger meaning to everything. She seeks in a way that Matty cannot – because she comes from a place of larger understanding, of participation in the world.

As a writer who veers instinctively towards the multi-stranded narrative, I find Darkness Visible to be a miracle of construction, its strands linked together not just through the reappearance of familiar characters but through the interacting perspectives of those characters. Hence we are told that Matty first encounters Sophy and Toni Stanhope as ‘two enchanting little girls’ gazing into the window of Goodchild’s Rare Books, or that Sebastian Pedigree’s return to Greenfield after his first spell in jail coincides with their mother Muriel Stanhope’s leaving.

Golding’s breaking of the fourth wall is a subtle thing, a slipping glimpse of postmodernism rather than a full immersion, yet it is a beautiful thing nonetheless and contributes significantly to the novel’s weirdness.

Darkness Visible takes place in the real world and has a sharp realworld awareness of contemporary politics and changes in society. Though the novel does contain turns of phrase and outdated usages that come across as dated and paternalistic in a modern context, Golding’s desire not only to reflect but to understand a rapidly changing world is powerfully apparent. The disenchantment and disillusion felt by the novel’s younger characters – with time on their hands and aching for purpose – seems both echo and indictment of the realworld violence perpetrated by European fringe organisations of the time, such as the Red Brigade in Italy, the Baader Meinhof gang in Germany, and the IRA in Belfast and on the British mainland. Sophy is an astonishingly vivid character, and Golding’s portrait of an exceptional woman is still something out of the ordinary. Similarly, his portrayal of Pedigree – ‘the sort of man whom a policeman feels in his bones should be moved on’ – is as shockingly direct as Nabokov’s depiction of Humbert Humbert in his masterpiece Lolita.

Yet Golding’s central literary purpose seems a million miles from social commentary. There is a mythic, interior quality to his narrative that renders it timeless. Sophy’s ‘desire to be weird’, her ‘hunger and thirst after weirdness’ is both an invigorating necessity and a deadly curse. Both Sophy’s narrative and Matty’s come suffused with the ‘homespun magic’ of which John Bailey speaks in his 1979 review. Even Frankley’s ironmongers – ‘a fine old establishment’ – has a feel of Steven Millhauser about it, or the porcelain showroom in Richard Adams’s ghost story The Girl in the Swing. Its infinite spaces, its cavernous lofts, its cobwebby rooms stacked with useless treasures seem suffused with the ability to become or to conceal a whole world, a snow-globe cosomorama of a life long past. Eventually, symbolically, we see the Frankley outbuildings being demolished in the novel’s Part 3.

The trajectory of the narrative – the overall story arc – is finally an affirmation of the novel’s weird nature, the fulfilment of its own prophecy. Edwin Bell, retired teacher and former colleague of Sebastian Pedigree at Foundlings School, believes Matty to be some sort of prophet, a Delphic oracle for our troubled times. Sim Goodchild, the proprietor of the bookstore whose business is failing, believes no such thing. For Goodchild, modern life is all hard logic. And yet we cannot help remembering Matty’s encounter with an official who tried to help him during his earlier ill-fated sojourn in Australia, a man who treated Matty as an equal, whilst at the same time warning him that his sacred message – his prescient foreboding of a planet in crisis – would forever be doomed to fall upon deaf ears.

The secretary takes Matty’s gestures seriously, yet stands apart from them. When he asks Matty if he has the second sight, if he ‘sees’, Matty replies: ‘I feel!’ an impassioned declaration that works equally as a vindication of the novel as a whole.