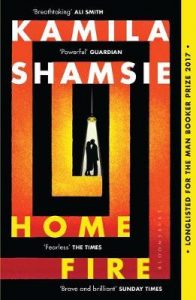

I remember reading a slightly strange article a couple of years ago about how in times of crisis or political turmoil, the act of reading or writing fiction could begin to seem irrelevant, a sideshow. We should be reaching for deeper truths, more urgent subject matter. This argument would appear to be more persuasive now even than when the essay was written, and there is a part of me that identifies with the sentiment behind it. I examine my motives in writing fiction much more closely now than I did when I started out, interrogate myself constantly about what kind of fiction I want and need to be writing. I believe that these are healthy and valid questions for any writer. But think about it for more than five minutes and you’ll see that questioning the validity of fiction as a means of understanding the world is to ask the wrong question. The greatest fiction has always been more than an escape or a solace – see the hundreds of novelists incarcerated in gaols across the world as political prisoners who stand witness to that fact. In Home Fire, by Kamila Shamsie, we see how powerful a tool the novel can still be in highlighting the most urgent political questions of our generation, how directly and how boldly fiction can speak. That Shamsie has chosen to use mythic archetypes in telling her story only adds to its strengths, showing how even such a seemingly abstruse concept as literary form can have a pivotal role to play in the construction of a political argument.

I remember reading a slightly strange article a couple of years ago about how in times of crisis or political turmoil, the act of reading or writing fiction could begin to seem irrelevant, a sideshow. We should be reaching for deeper truths, more urgent subject matter. This argument would appear to be more persuasive now even than when the essay was written, and there is a part of me that identifies with the sentiment behind it. I examine my motives in writing fiction much more closely now than I did when I started out, interrogate myself constantly about what kind of fiction I want and need to be writing. I believe that these are healthy and valid questions for any writer. But think about it for more than five minutes and you’ll see that questioning the validity of fiction as a means of understanding the world is to ask the wrong question. The greatest fiction has always been more than an escape or a solace – see the hundreds of novelists incarcerated in gaols across the world as political prisoners who stand witness to that fact. In Home Fire, by Kamila Shamsie, we see how powerful a tool the novel can still be in highlighting the most urgent political questions of our generation, how directly and how boldly fiction can speak. That Shamsie has chosen to use mythic archetypes in telling her story only adds to its strengths, showing how even such a seemingly abstruse concept as literary form can have a pivotal role to play in the construction of a political argument.

In Sophocles’s Antigone, the titular character petitions King Creon of Thebes for permission to bring home the body of her disgraced brother Polyneices for a proper burial. King Creon refuses, and when Antigone carries out funeral rites for Polyneices in direct contravention of his orders, he demands that she be captured and executed. Antigone’s sister Ismene tries to remonstrate with the king, offering to die in her place. Antigone’s fiance Haemon – Creon’s son – though initially shocked by his beloved’s transgression, attempts to placate his father, begging him to spare Antigone and allow her to return home. Creon wavers, eventually acquiescing to his wife’s entreaties, that mercy be shown towards the young people as the gods would wish. In the manner of classical tragedy, his decision comes too late: Antigone has hanged herself, Haemon likewise commits suicide when confronted with her loss. Creon has saved his throne, but lost everything that mattered most to him in the process.

Home Fire begins with a sleight of hand, a deft and understated precis of what is to follow. Isma is at the airport. The eldest of three siblings, she has spent the past six years caring for twins Aneeka and Parvais, following the deaths of their grandmother and mother in quick succession. The twins are now nineteen, on the brink of going their own way in the world. Isma can return to the life she was expecting to live, fulfilling her cherished ambition to take up a research scholarship in the US. Though her paperwork is in order, Isma is detained at passport control, interrogated at such length about her purpose of travel that she misses her flight. On arrival in Boston, she tries to put the incident behind her, but the forces of politics and circumstance are already moving against her. The siblings’ father was a known jihadi who died while being transported to Guantanamo Bay. Their father was never around much – the twins have no real memories of him – but still, his outlaw status has been enough to keep the family on MI5’s radar. More devastatingly still, Aneeka’s twin brother Parvais has fallen under the influence of ISIS supporters and been persuaded that his place is in Raqqa, fighting the fight in honour of the hero father he never knew. Isma is furious – she blames Parvais for putting the whole family’s security at risk through his selfishness. Meanwhile Aneeka, desperate to be reunited with her brother, begins a relationship with Eamonn Lone, the son of ‘Lone Wolf’ Tory Home Secretary Karamat Lone, the one man who has it within his power to grant permission for Parvais to return home.

The airport detainment scenes aside, the opening chapters of Home Fire are deceptively bland. We see a young woman embarking on the next stage of her life, making new friendships, falling in love. It is only gradually, as parallel plot lines draw inexorably together, that the narrative begins to take on the characteristics of Greek tragedy. Shamsie’s novel makes for an extraordinary reading experience, both at the level of story and in terms of its formal execution. Home Fire‘s relationship with its legendary precursor is subtle, striking, brilliantly clever, the extent of the narrative’s involvement with its source material only becoming fully apparent as the novel nears its conclusion. It could be argued that Shamsie’s characterisation is a little flat, that the characters’ identification with mythic archetypes renders them prisoners of the plot – but this also works in the novel’s favour, strengthening the bond with Antigone and revealing how myths are made. Personally, I found the characters managing to break free of their preordained roles just sufficiently to make them compelling in their own right, Aneeka and Parvais particularly, with Shamsie’s use of language – never less than excellent in terms of its craft – attaining a special resonance and beauty throughout those passages.

For me, this was a heart-pounding, heart-breaking narrative of great power and importance, the kind of novel you want to press into people’s hands. Ideally, Home Fire would be read by everyone in Britain, right now. That’s how relevant it felt to me as fiction.

After finishing Home Fire, I remembered an article Shamsie wrote for the Guardian in 2014, detailing her own experience of applying for British citizenship, Ideally, everyone should read this too, and ask themselves what it means for Britain when even an artist who continues to make an incalculable contribution to the cultural life of both her countries can be made to feel despair and panic in the face of this bureaucracy, a political culture that directly opposes every ideal it is said to espouse. As a writer, Shamsie was deemed ineligible to apply for leave to remain, because that category of application was abolished – writers, artists and composers are no longer of material value to British society, it seems. If she’d been trying to apply now, she would have found the goalposts moved again – she would been deemed ineligible on grounds of not having a big enough bank balance.

Britain is a poor sort of place right now, frankly. Home Fire shows us some of the ways we are being made poorer.