Having concluded his story, he opened the door to the church. Inside were ruins, on which bushes and saplings had sprouted. Through the broken windows we could see a bleak sky. A mute church bell hung above us.

We all looked up.

“See, ” our teacher said, “the bell had its tongue torn out. It can no longer ring.”

Later, by a campfire near the church, over sandwiches and tea, the teacher asked us what thoughts the bell had inspired.

As always, the wunderkind had to be different. He said that the bell had been lucky in a way, because it never had to worry about holding its tongue again.

Everyone, including Teacher Blums, laughed heartily.

“And what do you say?” the teacher asked me.”

Everyone gazed at me in silence. The fire was crackling. The flames and the silence burned my cheeks.

“That bell reminds me of my mother.”

The silence and the crackling grew louder.

*

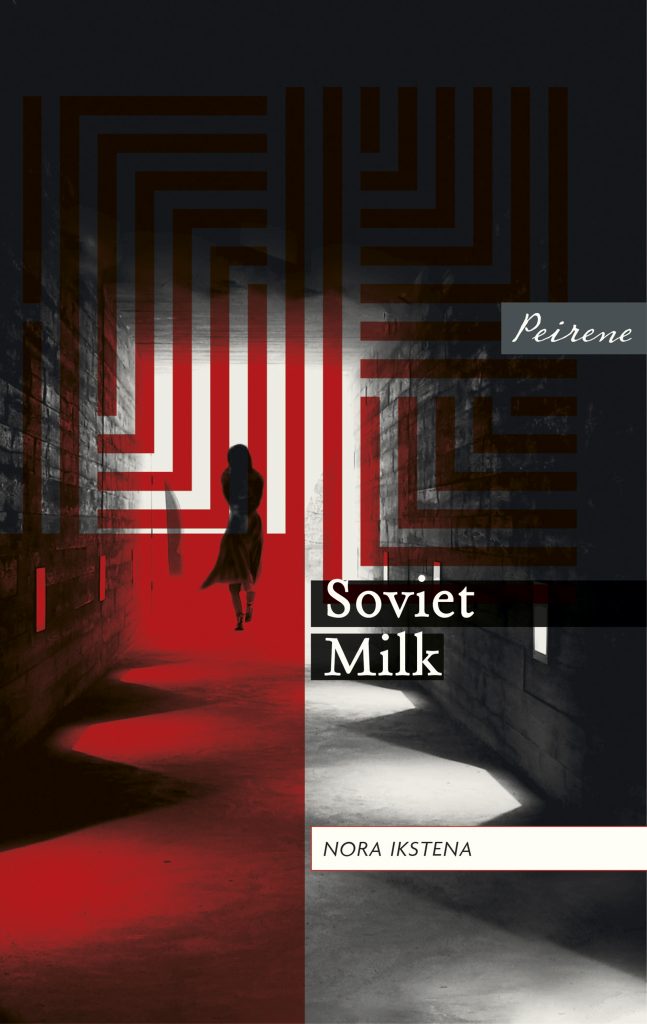

The unnamed mother and the daughter in Nora Ikstena’s Soviet Milk are more or less the same age as me and my own mother. There are other parallels, too. As a student, I spent three months in the Soviet Union at the same time the daughter would have been in her final year at school. I lived in dormitory accommodation first in Leningrad – where the mother in Ikstena’s novel sets out to study medicine – and then in Kursk, not far from the Russian border with Ukraine. Already at that time there was a marked difference in atmosphere between Russia’s second capital and the moderately sized, provincial city in the heart of the Soviet interior. In Leningrad, people were beginning to engage openly in political discussion – there were demonstrations on the streets, excited gatherings of young people eager to discuss everything from God to McDonald’s.

In Kursk, we were still on Soviet time. The city’s skyline was still dominated by statues of Lenin and Marx and you felt they still meant business. Vast placards at every street intersection shouted Soviet slogans. The young people here had never met British students before. They were excited and beyond hospitable but you could also sense their caution – not at us, but at who might be watching them interact with us.

Most afternoons after our classes we swam in the river, like the mother and daughter and Jesse in Soviet Milk.

Ikstena’s novel is blisteringly beautiful and hauntingly sad but more, far more than that it is tenacious. It tells the story of what half of Europe lived through once they got rid of the Nazis. Reading Soviet Milk reminded me painfully of reading Christa Wolf’s Nachdenken ueber Christa T, which is a book of my heart. When I read Claire Armitstead’s review – ‘its powerful evocation of an era that seems almost unimaginable now’ – I felt sad and somehow cheated. For millions of people, on both sides of the wall and for different reasons, that era forms the spine of their being and is still very present. Would we say that the Thatcher era is almost unimaginable now? Sadly, I don’t think we would.

The mother in Soviet Milk reads Moby-Dick and 1984 – Ishmael and Winston Smith are her comrades in arms. The mother’s refusal to compromise – her inability to live inside a situation that demands compromise on pain of ruin – is tragic yet she is a great soul, a powerful intellect, a modern martyr. The daughter’s contrasting and ferocious desire to thrive – to win freedom – makes her equally so. I loved these two people. I loved the stalwart Jesse, an intersex woman living at a time that denied her very existence. I loved the constantly illuminating presence of the natural world, which sustained these women through their journey – even the cold.

I felt a particular gratitude for Peirene Press’s and translator Margita Gailitis’s decision to leave the text of Soviet Milk interlaced with different languages, sometimes in parallel text format: Latvian of course, transliterated Russian, even Old Church Slavonic. The power this brought to the novel as a whole – in terms of nuance, in terms of form – is inestimable and precious.

This morning I listened to a news item about a Saudi government app – now ubiquitous – that allows Saudi men to register their female relatives and receive text messages whenever their wife, daughter or sister boards a plane or passes through some other travel checkpoint. Yesterday I read about a 90-year-old man who is being forced by our government to return to the United States – a country where he has no remaining family or close friends – in order to complete a visa formality that will enable him to remain here in the UK with his wife and family. State oppression is not unimaginable – it is here, and everywhere. Soviet Milk may tell a story set in the second half of the twentieth century but it is a story for all of us, now.

I loved it very much.