When your choice is to work or to die, that is not a choice. But Sao Paulo was no choice, either. It was a bad death, when this world was more than rich enough to ensure we could all eat, that no one needed to die of the flu or gangrene or cancer. The corps were rich enough to provide for everyone. They chose not to, because the existence of places like the labor camps outside Sao Paulo ensured there was a life worse than the one they offered. If you gave people mashed protein cakes when their only other option was to eat horseshit, they would call you a hero and happily eat your tasteless mush. They would throw down their lives for you. Give up their souls.

The future of Earth looks grim. Ten generations hence, the world’s premier power-brokers are not elected governments, but massive corporations, engaged permanently in a battle for supremacy amongst themselves. If you’re lucky enough to be a full citizen, you have access to healthcare, safe working conditions and subsidized training programs. As a mere resident you would be less privileged, able to live and work without persecution but with few actual rights. Fall foul of the status quo in any way and you’ll end up a ghoul, scavenging for resources in one of the vast undocumented labour camps, no one giving a damn if you live or (sooner rather than later) die.

On Mars, colonists who were once citizens have broken away from the corporations to form their own ‘free’ republic. Sensing that the Martian revolution could spread back to Earth, the corporations have vowed to wipe out their insurgency. Dietz grew up as a resident of the corporation city of Sao Paulo, only to see what was left of her family destroyed in an act of genocide known as the Blink. The corporation insists the Blink was perpetrated by Mars. Dietz joins the army hoping for the chance to make a difference – and possibly to become a hero. As she readies herself to face the Martian enemy, Dietz must also prepare for the additional dangers of life as a soldier in the Light Brigade: in order to cross the vast distances of space, soldiers are made to attain the speed of light by literally becoming light. Not all of them survive the process. A few, like Dietz, are being transfigured in ways the corporation never intended.

As Dietz’s timeline becomes ever more confused, she begins to understand that the enemy she has been fighting is not who she thought they were, that the war designed to defeat them appears to be unending. Even as her knowledge grows, each ‘drop’ presents a new risk of death. As Dietz struggles to outrun her masters, she finds her old ideas about heroism and soldiering coming increasingly under fire.

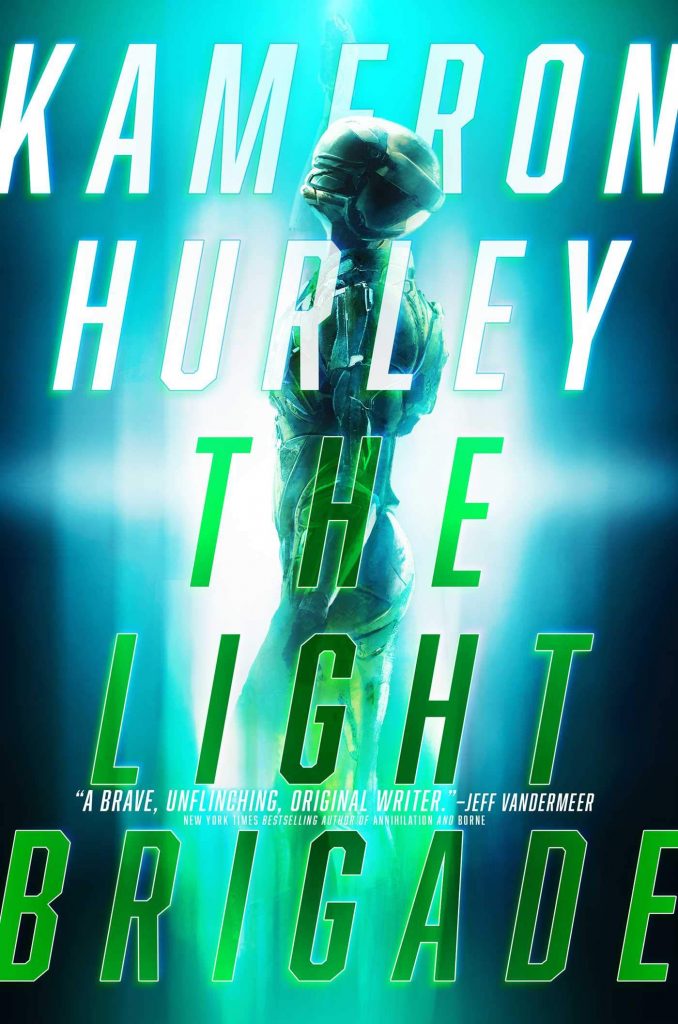

What a ride, what a charge. Kameron Hurley was last shortlisted for the Clarke Award back in 2014, for her debut novel God’s War. I enjoyed and admired God’s War, but had fallen somewhat out of touch with Hurley’s work since, so I was pleased to have the opportunity to read her latest within the context of the Clarke. What a delight it is to see a writer fulfilling her potential. What I loved most about God’s War and the short fiction from Hurley that I’d read in the interim was its densely textured language, and The Light Brigade is immediately, thrillingly identifiable as by the same hand. Time (and increasing fame) has done nothing to slow or flatten the vividness and immediacy of Hurley’s approach, nor compromise its intelligence or conceptual ambition.

What time (and experience) has done for Hurley is exactly what it should do for a writer, that is, to strengthen and deepen her technique. The Light Brigade is a remarkably complex piece of plotting. In less capable hands, the timeline could have become either too confusing or else reliant on clumsy exposition. Hurley nails it beautifully, presenting us with a story that is not only fast paced (and how!) but finely detailed and emotionally impactful. All questions are finally answered, and in a satisfying way. The order of events is complex but stick with it and you’ll discover everything makes sense. The characterisation is deft and moving – you really do get to know these soldiers, to fear for them, to care for them. Hurley’s language is leaner and meaner than it was in God’s War, maybe, but its beauty and personality is present, correct, and firing on all cylinders. The dialogue is particularly commendable: pacy and entirely contemporary whilst retaining a genuine individuality and never sliding into movie cliche.

For anyone who enjoys MilSF – and equally for those who think they don’t – The Light Brigade could be their novel of the year. Hurley’s interrogation of war’s crossed purposes, its vested interests, its abuses of loyalty and twisting of facts, its many ways of consolidating power in the hands of the powerful is righteous and damning and expertly argued. I need hardly mention that her treatment of gender and personal identity is not only bang on, but seamlessly integrated into the text. This novel is exciting and highly charged and it augments and enhances those qualities by being politically literate in a way that is deeply relevant to our times.

The everyday person doesn’t want war, but it’s remarkably easy to convince them. It’s the government that determines political priorities, and it’s easy to drag people along with you by tapping into their fear. I don’t care if you have a communist mecca, a fascist regime, or a representative democracy, even some monarchy with a gutless parliament. People can always be convinced to turn on one another. All you have to do is convince them that their way of life is being attacked. Denounce all the pacifist liberal bleeding hearts and feel-good heretics, the social outcasts, the educated. Call them elites and snobs. Say they’re out of touch with real patriots. Call these rabble-rousers terrorists. Say their very existence weakens the state. In the end, the government need not do anything to silence dissent. Their neighbours will do it for them.

Although The Light Brigade works perfectly well as a standalone novel – you don’t need to have read any of Hurley’s other work or even any science fiction to get on board – it is important to note the many and clever ways in which it is directly in conversation with older works of SF. I have not yet read Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers but from my brief researches around the text I can see how a good portion of The Light Brigade’s polemic lies in strenuously confronting Heinlein’s glorification of the military lifestyle and moral code, his proposition that only those who bear arms should have full rights of citizenship, including the right to vote (???!) I have read Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War, the other novel that Hurley’s is clearly in dialogue with, and while ideally I would have reread that book in order to have a proper discussion of it here, time has run out on me. Whilst confirming and supporting many of the arguments set forth by Haldeman, Hurley updates, redresses and clarifies issues of gender and representation that were (perhaps understandably) less fluently handled in the earlier novel.

This is all part of the joy of what the SFF community calls the conversation. Hurley has not only written a tense, original and beautifully executed novel, she has contributed at a high level to the ongoing SFF discourse, using her knowledge of (and beef with) works and writers that have gone before to expand and advance the arguments and preoccupations of science fiction as a literature. There’s even a nod to Ursula Le Guin’s 2014 National Book Award speech about the divine right of kings.

This kind of homage can only be fully successful if the newer writer is technically and creatively the equal of her predecessors. Hurley is all of that and then some. Politically astute, expertly handled and a damn fine read, The Light Brigade is fully deserving of its place on the Clarke Award shortlist, and sets the standard for military science fiction for years to come.