‘If you did kill him,’ she said in a whisper, ‘and if someone else found him that night – they might have been afraid to report it. Don’t you think? Some people are like that. They’d rather walk away – or push the body into a canal.’ Her brows trembled.

Everybody would rather walk away, Ray thought.

*

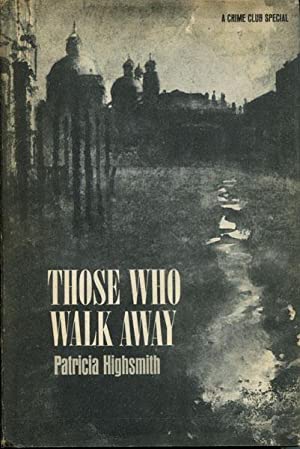

Trust me to begin this challenge with the last item on the list! This was actually a re-read, so I might feel tempted to double up on this category later in the year with something entirely new. But revisiting Highsmith is always a joy and always time well spent.

Patricia Highsmith is routinely described as a crime writer, a label she herself found irksome as she disliked being categorised – she thought of her books simply as novels, and did not see the need or point of allocating them to a particular genre. Given Highsmith’s genius for writing crime novels in which no crime takes place, her ambivalence around the term is understandable.

There are some very nasty murders in Highsmith; equally, there are books of hers in which the shadow of murder hangs like the sword of Damocles over the entire proceedings without ever falling. This seeming unwillingness to commit herself wholeheartedly to the traditional form of the thriller, in which a crime is committed, generating situational or moral chaos before eventually being resolved, preferably with the villain getting their deserved comeuppance, did not endear her to her American editors. In Europe, the interior, almost philosophical nature of her novels has ensured for her work a popularity that extends far beyond the Ripley novels and Strangers on a Train.

I return to Highsmith’s books again and again because they offer a radically different interpretation of what is meant by crime fiction. Her novels offer us questions with no firm answers: if we can read crime novel knowing from the outset that no crime takes place, what exactly is it that we are responding to? And what are the particular properties that make crime fiction so compelling?

In Those Who Walk Away, Rayburn Garrett is a young art dealer whose wife, Peggy, has recently committed suicide. Ray is distraught at her death, and plagued by an unfocused sense of guilt that he should have been able to foresee what was coming, and did not. Peggy’s father Ed Coleman has no doubt that Ray is to blame – he considers him feckless, charmless and insensitive, and the more he dwells on his daughter’s death, the more his grief becomes tangled up with his obsessive and irrational hatred for his indolent son-in-law.

After making a half-hearted, one might almost say experimental attempt on Ray’s life in Rome, Coleman heads for Venice with his current mistress Inez and an entourage of hangers-on. Inez pleads with Ray that he should not try to see Coleman, that he is not in a state of mind to listen to reason. Ray promises her he will leave Venice without speaking to him, then does the exact opposite. What plays out over the next fortnight or so is a kind of duel, a chase in slow motion through the wintry streets of a city bedding down for the off-season. There are acts of violence, but none of them prove fatal. There are acts of deception, but in true Highsmithian fashion these are wilful and ultimately pointless. The moments of highest tension are generated from brief sightings in a busy street, inconclusive phone calls, the imagined repercussions of a confrontation that never plays out.

Part of the magic for me during this reread was being able to keep track of Ray and Coleman via Google Streetview. When I first read Those Who Walk Away, which must have been about twenty years ago, there was no such thing. Still, I remember being entranced by Highsmith’s portrait of Venice, which is unsentimental to the point of being mundane. Her writing reveals the city’s split identity, its humdrum aspect, which might never become apparent to those who come as tourists.

Highsmith knew Venice well but had something of an on-off relationship with the place. Her descriptions leave us in no doubt of the city’s beauty as it is perceived by its millions of visitors, but they make us aware also of the ways in which for those who live there, Venice is entirely ordinary. Highsmith’s Venice is a city where working people go to and from their jobs, where small, backstreet cafes have their regular morning clientele, where grievances are settled behind closed doors and minor corruption flourishes. Bad weather settles in for days. Unwary Americans shiver in unheated lodgings. Life goes on.

As Coleman and Ray pursue each other through the less frequented backstreets, I found myself checking their locations online, compelled to glimpse something of what they might have seen, not just the thronged and glittering quaysides of Zattere and Schiavoni but also the plainer, less frequented back lots and alleyways of Chioggia and Giudecca, where Ray and Coleman alternately take refuge in the homes of ordinary Venetians.

And of course I fell more in love with the myth of Venice than ever, of course I’m all the more determined to finally visit, once travel becomes less insane. I shall go in the off season, when it’s chilly and when, or so I understand, there are marginally fewer people. I want to sit in a cafe and read, in an unknown little square somewhere. I want to reread Invisible Cities, and think about Ray spinning falsehoods to Elisabetta and finding he cannot bear to leave the city until he has settled the business of Coleman once and for all…

Early on in the narrative, Ray buys a silk scarf he happens to notice in a shop window because it seems so exactly like the kind of scarf his wife Peggy might have owned and treasured. A chapter or two later, Coleman notices the scarf, which Ray has pulled out of his pocket by accident, and demands Ray hand it over. He immediately assumes that it is Peggy’s, and that as such he has a right to it. Ray feels aggrieved and affronted whilst at the same time nurturing a feeling of vindicated spite: the scarf isn’t Peggy’s, so more fool Coleman. This scarf becomes a symbolic stand-in for the acts of duplicity, of mistaken-ness, for the unprovable lies that criss-cross the narrative. It might also be taken as a cipher for the novel’s most notable absence, that is, Peggy herself.

I don’t just mean that Peggy is dead before the novel opens – we never actually get to meet her as a living person. What comes across still more strongly is the fact that neither of these men who are purportedly fighting over her – locking horns like stags, the old king and the venal upstart – would seem to have the slightest clue about who she really was or what she was like.

Both Coleman and Ray go along with and contribute to the received opinion about Peggy, that she was ‘unworldly’, idealistic, more child than woman, that she was somehow ‘disappointed’ by the reality of life and so decided to end it. Her presence flickers at the corner of our consciousness, barely seen, ghostly, not just because she is dead but because no one seemed to pay her sufficient attention when she was alive.

We know that like her father she was a talented artist – but neither Ray nor Coleman seems much interested in why she more or less gave up painting in the months before her death. Coleman’s grief comes across mostly as the inarticulate, violent rage of a man rudely divested of a valuable possession. As for Ray, he seems mostly to have forgotten Peggy, to have reduced her to an idea, a pretty silk scarf. The conflict he engineers with Coleman is far more interesting to him, far more vital.

As with every duel ever fought, this was never about the woman. It’s a dick-measuring contest. I would love to know if Highsmith herself saw it that way, though I suspect not. Men like Coleman and Ray fascinated her in and of themselves for the curious nullity, the restless dissatisfaction at the heart of their obsessions.

As a writer, I feel there is so much I can learn from Highsmith. Again and again she delivers books in which craft and art are in symbiosis, perfectly weighted and working as one. Her writing is never showy – there is a pared-back, less-is-more quality to it that nonetheless has an element of refinement and literary knowingness that is woefully absent from much of today’s ultra-slick thriller writing.

The landscape of her books – street scene, social milieu and most of all the atmosphere of certain bars, restaurants, hotels, resorts and apartment buildings – is memorably evocative. Rather than relying on hectic and unconvincing circumstantial twists, the drama of her peculiar plots is rendered more or less entirely through the medium of character.

There is no trickery, no formal fireworks. The stories Highsmith tells appear to be simple, even uneventful. Yet there is something, a perplexing oddity, a fierce beauty that makes them both readable and memorable. You may not always get a murder but Highsmith has a way of highlighting the strangeness at the heart of normality that might make you imagine a murder where none has taken place. That’s how it is at the end of Those Who Walk Away. We don’t really have a clue what Coleman and Garrett are going to do next, whether they’ll never see each other again, as each insists, or whether their bizarre duel is going to continue until one of them dies.