I have a steampunkish obsession with things that work. I’m as enslaved by my computer and my smartphone as the next person, yet I am uncomfortable with the way we take them for granted, without having the least idea of how we might get them up and running again if they suddenly stopped. I can’t put together a wireless set or a combustion engine either, but I can look at the diagrams with all those arrows and pointers, connect bits of wire on a circuit board and feel at least half way convinced that given the time and the necessity a basic level of mechanical engineering is something that I could conceivably learn. I can see where the parts interlock, grasp the laws of physics that govern that movement. When I was at school doing ‘O’ Level Physics and Mathematics I tended to let this stuff glide over my head, memorizing (just barely) the requisite facts to get me through the exam but nothing more.

More recently I’ve found that has changed. I find comfort and security in the basic laws of physics. I have become fascinated by the habits of simple machines. One day about five years ago I found myself looking into a jeweller’s window in Blackheath at the wristwatches displayed there and feeling an unaccountable sadness that they were all and without exception battery operated. My first watch, given to me for my birthday when I was eight, was a Girl’s Timex Wristwatch and a perfect miracle of clockwork engineering. All watches were mechanical then. We took it completely for granted that they actually ticked. I remember the first child in my class who came in wearing a Casio digital watch being instantly surrounded by his friends, all of them eager to try out the alarm (a very first, primitive version of the ringtone), to see the little light that came on when you pressed a button at the side, to watch the numbers click over from 12:55 to 13:00.

I suppose I was fascinated too but I still thought the thing was ugly. I didn’t want one, I remember that. It never occurred to me that what I was looking at was the future.

After staring at those Blackheath watches for a while I went back to my flat and ran (yes) a computer search for mechanical watches. The first thing I wanted to know was how a watch worked. I printed out a lot of diagrams and in the end I got a sense of it, the sequence of mechanical processes that allows the second hand of a clock to tick off those seconds. In terms of story it was like a window opening, a way of seeing time as a material thing, something you could weigh and measure and perhaps even alter, rather than something that simply passed, or even passed simply.

I also began to learn about the great watchmakers, men like Breguet and Harrison and Lange who really were the rocket scientists of their day. To my delight, I discovered that there are still people out there making bespoke mechanical watches, timepieces, objects of both beauty and (as William Morris stipulated) an inherent and integral usefulness. There is even an academy for such maniacs, the AHCI (or Academie Horlogere des Creaturs Independants) which at approximately 30 members must count itself one of the most exclusive clubs in the world.

I couldn’t not write about this. The obsessive quest for perfected achievement is what drives a writer or a watchmaker or any artist, and as such it is an area I come back to again and again in my own writing. A watch is a thing of tiny parts, and yet the subject seemed so large and so…. complicated to me that I didn’t know at first what to do with it. It therefore felt logical to create a hero who felt the same. I had his uncle give him a watch for his birthday, as I had been given my little gilt Timex by my parents, and waited to see what might happen.

I ended up with a lot of material, which gradually and over time I began to separate into particular stories, or episodes, chapters that seemed to form the parts of a larger whole. I did other work in between, but Martin Newland and his time-slippages kept drawing me back. I had a couple of the stories published as standalones, but something insisted that wasn’t the end of it.

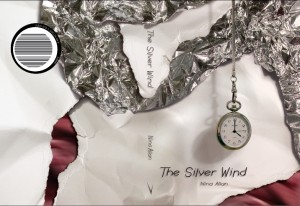

Finishing ‘Rewind’ a month or so ago was an important moment for me because it meant the ‘Martin stories’ finally formed a kind of circularity. They belonged together, and thanks to David Rix at Eibonvale they could be published together. Some of my friends have suggested that The Silver Wind is actually a novel. I can see what they mean, but I don’t think I altogether agree with them. The stories in this book may be about the same people and places, but they were written months and in some cases years apart, and each functions independently of its companions. The Afterword, the shortest segment in the book but the hardest to write, is a piece of fictionalised memoir. But if Wind isn’t a novel then neither is it a straightforward collection of stories. In truth, I don’t know what it is. I’d rather just call it a book.

It’s been a bit of a back-and-forth, this one, and there were times when I thought that most of this material might be doomed to languish on my hard drive forever. But finally the book is here, and it is with great pleasure that I can announce that it is further enhanced by an introduction from Tricia Sullivan. I first met Trish at EasterCon this year, and her support for and thoughts on The Silver Wind have been a huge compliment to me, and a marvellous encouragement.

The book’s official launch will be at FantasyCon in Brighton over the weekend of September 30th – October 2nd, where I will be giving a reading and signing copies. But for those of you who can’t be there, you can pre-order a signed copy as of today from the Eibonvale Press website. David Rix has also blogged about the book here.

I might also add that Martin’s story might not yet be over. There’s one last sizeable chunk of work on that hard drive, a novella that deals with the childhood and apprenticeship of my own mad watchmaker Owen Andrews. It needs redrafting, and it’s far from ready. But I can’t quite bear to throw it away….

(Image by Hustvedt)