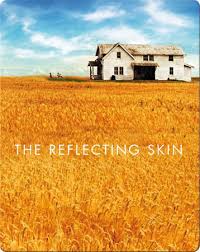

Over the weekend I finally managed to catch up with, via the recently reissued DVD of the film, Philip Ridley’s first feature The Reflecting Skin (1990).

Over the weekend I finally managed to catch up with, via the recently reissued DVD of the film, Philip Ridley’s first feature The Reflecting Skin (1990).

On the face of it, this is a simple coming-of-age story. Our eight-year-old hero Seth is growing up in rural Idaho in the early 1950s. WW2 is still a recent memory. Seth’s parents, Luke and Ruth, cope with the absence of their elder son Cameron, who is with the US armed forces in the Pacific, largely by ignoring each other, scraping by on the proceeds from their one-pump gas station. When one of Seth’s young friends turns up murdered, the local sheriff seems determined to point the finger at Luke, who was once cautioned for ‘indecent behaviour’ with a seventeen-year-old youth. Seth has other ideas. A near-neighbour, Dolphin Blue, harbours fantasies of violence and keeps mementoes of her deceased husband Adam – dead from suicide – in a locked box. Having been told about vampires by his father, himself an avid reader of pulp magazines, Seth believes the seductive Dolphin to be the true face of evil at the heart of their tiny community. As the recently returned Cameron falls ever more deeply in love with Dolphin, Seth becomes increasingly desperate to warn his brother of the danger he faces.

In the naivete of its child protagonist and its unintended tragic consequences, we might draw strong comparisons with such movies as Losey and Pinter’s 1972 classic The Go-Between and Joe Wright’s more recent Atonement and we would be right to do so. In their portrayal of misplaced jealousy, burgeoning sexuality, terror and envy of the adult world and the febrile intensity of the juvenile imagination, these films form a natural trilogy almost. That they all take place under the heat of ‘that last summer’, a span of time that seems destined to forever change the lives and futures of those who pass through it, draws such comparisons still tighter.

Interestingly though, Ridley’s film stands alone here in taking place in ‘real time’ rather than through the clarifying lens of hindsight. We can only guess at how the adult Seth might be affected in future – not just by what has happened, but by his own particular part in it. This is a dark tale, richly informed by Dick Pope’s superb cinematography, Nick Bicat’s ravishing score (fun fact: Bicat also wrote the music for the 2002 TV adaptation of Ian McEwan’s ‘Solid Geometry’) and Ridley’s own inimitably concise and emotive screenwriting. The imagery on display here – Dolphin’s memory box, Cameron’s photos, the mummified foetus, the nuclear sunsets, the teddyboy ‘vamps’ in their black Cadillac – is of a high and potent order. The only word that seems to fit this film is ‘Ridleyesque’.

I first encountered the work of Philip Ridley when I saw, completely by chance, his 1995 feature The Passion of Darkly Noon on late-night TV. Always on the lookout for interesting and out-of-the-way horror cinema, I was blown away by it. I also could not understand why so few people seemed to have seen this film or even heard of it. The themes were serious and deep, the vision complex, the writing and acting superb. The fact that this unique film has still never had a UK DVD release is a source of abiding mystery to me.

Ridley clearly likes to take time over his work, and it was more than a decade after Darkly Noon before he returned to the screen with the brilliant Heartless. Ridley’s third movie presents an equally disturbing journey into the heart and mind of an isolated young protagonist, with a destination no less terrifying than the end-point of his first. Particular shout-outs here should go to Eddie Marsan – the price of the DVD (easily obtainable this time, thankfully) is worth it for his Weapons Man alone – and to Clemence Poesy, who you will no doubt remember for being brilliant in In Bruges. Again, this film has been more or less overlooked by the horror community, yet for me, Ridley’s movies are as equally deserving of attention as Ben Wheatley’s. What’s going on?

Could it be that Ridley’s themes – his preoccupation with religious belief, faith, sin and self-destruction – are seen by some as contentious and unfashionable, maybe off-putting to viewers? If so, then that’s just Ridley doing his job! He does not simply recycle old tropes – vampires, demons, ghosts – to sanitized formulas as so many more commercial directors are wont to do. He takes the tropes apart, examines them for substance, shows us what might happen when dangerous ideas are followed through to their logical conclusion. If you’re seeking comparison, think Guillermo del Toro before he went Hollywood – the del Toro of Cronos and The Devil’s Backbone. Philip Ridley is as good as that, perhaps better. He is a master of the weird, and I just hope we don’t have to wait another decade to see his next masterpiece.