When he looked at the ceiling of the shabby room, the damp patch over in the corner and the crack around the lighting surround, and the repeated crescent stains where somebody had bounced a dirty ball on the ceiling the fragility of it all was overwhelming and the beauty, too, because there was Marty’s sweatshirt lying in illuminated folds like a sleeve from one of those old paintings, and there were the towels, brilliant white on the floor: centuries of people had cleaned away the dirt from sheets and towels, pummeling at the stains and the grime, rinsing it all away, the water circling down the drain, and endless lines of washing, high in the sky, billowing in a hard wind. (‘Last Supper’)

A good short story should reveal a corner of a world. It should tell a story, of course, but of equal importance to me when I am reading is the sense of a hinterland, of the author introducing us to places and to people who form part of a complete vision, with their lives and the lives of others continuing – perhaps in unforeseen directions – long after the final page of this particular story has been read.

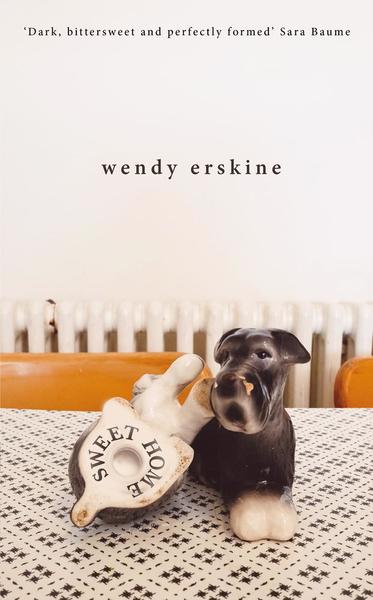

Wendy Erskine’s debut Sweet Home is a collection of small masterpieces. It is a book about Belfast but in contrast with David Keenan’s For the Good Times or Anna Burns’s Milkman it shows us the fallout from the Troubles in slipping glimpses – Kyle, who falls into a life of violence after suffering trauma at the hands of his father, or Olga, a lonely teacher whose married lover’s death in a punishment shooting has made her come to hate even the colour green.

Like Lisa Blower’s stories in It’s Gone Dark Over Bill’s Mother’s, which I read earlier this year, the stories in Sweet Home demonstrate an affinity for the form that makes them appear effortless, whilst at the same time employing ingenious twists and tricks of form and narrative that reveal an author who is not only fully conscious of the tradition she is working in but more than fully capable of ascending into its first rank of practitioners (Trevor, McGahern) – one of the stories from this collection, ‘Inakeen’, has already been shortlisted for the Sunday Times Short Story Prize.

Yet Erskine brings also a contemporary urgency and better still an empathy to her narratives that is all her own. Like so much of the great Irish short fiction writing, these are stories of ordinary working class people caught in the grip of everyday crises – and one never escapes the sense that Erskine is documenting rather than inventing, This is how it is, she seems to say. Given a twist or turn of fate, this could be you or me, maybe already is. These are stories of a society driven to breaking point, not just by the violence of armed conflict but by the more insidious, ubiquitous violence of unchecked capitalism.

In their pathos and in their power, these are stories of now.

I particularly loved ’77 Pop Facts You Didn’t Know About Gil Courtney’ – a life-in-fragments of an Ian Curtis-like musician – because come on, you know I love stories that do stuff like this with form. But the jewel in the crown has to be the title story, ‘Sweet Home’ itself, which apart from containing a real heart-in-mouth moment of horror, is a composite portrait of grief that manages equally to encompass all strata of society. ‘Arab States: Mind and Narrative’ also deserves particular mention for its stark and empathetic portrayal of a road-never-taken, as does ‘Lady and Dog’ for its neat nod to Chekhov. (I have faith that Olga does not realise her final, desperate act of imagining, by the way – there’s no way Erskine would do that to us.)

This is an involving and finely wrought collection and one that absolutely honours the memory of Gordon Burn. I only hope that Wendy Erskine is at work on a novel because I can’t wait to read it.