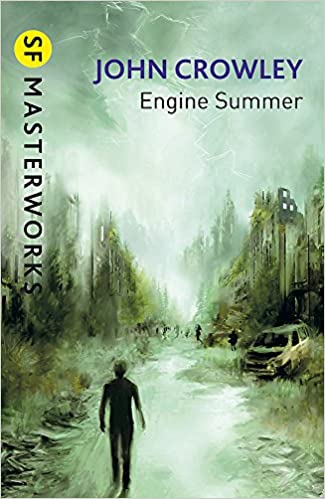

This past week I have mainly been reading John Crowley’s 1979 novel Engine Summer. It seems incredible that this book is now forty years old. It might also explain why, several times while reading it, I found myself thinking about John Christopher’s The White Mountains (1967), which for me has something of the same atmosphere, with Rush and Will’s quests and voices not so very dissimilar, and which I would probably have been reading for the dozenth time more or less exactly as Engine Summer was published.

Engine Summer is not what you would call an easy read. From the first page it is elliptical, self-concealing, with a sense not so much of the mysterious as the actively mystical. I enjoy tricky books a great deal, but I became aware early on that Engine Summer was setting itself up to be the kind of novel I don’t normally get on with at all – I’m not keen on fabulism, as a rule, and Engine Summer is not only fabulistic, it is at least partly about fabulism. As it turned out, I not only adored Engine Summer but now feel profoundly grateful to it. For being one of those texts that come along, periodically (and they always do) to jolt me out of my disillusionment with the science fictional mode, to remind me that no matter what kinds of arse might be going on in the community at any given moment, no matter how derivative so much of what is written can begin to seem, there will always be a through-line of texts that create and sustain the field, that provide the intellectual and aesthetic roughage to enliven and stimulate and further the conversation.

And what a stunning, humane, enlightening text Engine Summer is. What liberties it takes with our patience, always rewarded. Crowley’s handling of the post-apocalyptic (old tech viewed as magic, hidden connections with the long-past that are invisible to the narrator but of profound significance to the reader) is sure-footed and brilliant, and much appreciated by me, because old-tech-posing-as-magic is a trope I happen to love.

Most of all, Engine Summer is a beautiful book and a beautiful story. Crowley’s language – his landscape-writing especially – is the hook it all hangs on, the hook that kept me, well, hooked even in those early stages when I wasn’t sure about the rest of it. In laying out, further exploring and ultimately revealing its central conceit, Crowley’s novel is masterful – at no point could any science fiction purist accuse Crowley of taking refuge in either the stolidly mimetic or the overtly fantastical. That it is also masterful as a piece of text, in maintaining and indeed glorying in its core components – language and form – is a much needed poke in the side of anyone, and I mean from whichever side of the barricades, who insists on insisting that science fiction cannot be literature.

Blink said: ‘It was as though a great sphere of many-colored glass had been floated above the world by the unimaginable effort and power of the angels, so beautiful and strange and so needful of service to keep afloat that for them there was nothing else, and the world was forgotten by them as they watched it float. Now the sphere is gone, smashed in the Storm, and we are left with the old world as it always was, save for a few wounds that can never be healed. But littered all around this old ordinary world, scattered through the years by that smashing, lost in the strangest places and put to the oddest uses, are bits and pieces of that great sphere; bits to hold up to the sun and look through and marvel at – but which can never be put back together again.’

See what I mean about it being difficult to believe this book is four decades old? I came out of Engine Summer on a kind of high, feeling energised and nourished and excited and so glad I’d read it. Reading around and behind the book afterwards, i discovered that Ted Chiang cites Engine Summer as a formative work for him, and I’m not at all surprised. In an interview I read with him at The Believer, Chiang makes a comment I think more or less sums up the approach taken by Crowley in his science fiction, but that also seems to encapsulate for me, in a manner I’ve never found so satisfyingly and succinctly expressed, the essential difference between the speculative and the mimetic:

“Science fiction is known for the sense of wonder it can engender, and I think that sense of wonder is something that is generated by stories of conceptual breakthrough. I don’t know if a sense of wonder is engendered by stories of personal epiphany.”

Chiang uses ‘conceptual breakthrough’ here to mean making a discovery that allows the reader to understand the world in a different way, to consider the possibilities for change or development that such a conceptual breakthrough might allow. Looking back on my own reading, I can see it has been these kinds of breakthroughs – intellectual epiphanies, maybe, as opposed to personal epiphanies – that have provided my most energising and memorable moments of engagement with the genre.

Chiang is also great in describing what it is that makes him identify as a science fiction writer rather than simply a writer:

“Genre is a conversation between authors, between books, that extends over decades. And one of the reasons I definitely identify as a science fiction writer is because I want to be a participant in the ongoing conversation that is science fiction. My writing is informed by the books I’ve read, so it is a response to what other writers have written. I want to be in conversation with other works of science fiction.”

The full interview is here, and very worthy of your time.

I also made time to read Paul Park’s A City Made of Words (2019), one of the very excellent chapbooks in the Outspoken Authors series from PM Press. Each of these chapbooks features at least one previously unpublished story as well as an author interview, bibliography and other scarce material and one could gain a fantastic overview of what science fiction is ‘about’ and what it is capable of, simply by reading the volumes in this series. (Now there’s a project waiting to happen.)

Like John Crowley, Paul Park is an author clearly interested in stretching science fiction well beyond its generic envelope, and the results, for me, have made him a touchstone author. I hadn’t previously read any of the stories in A City Made of Words, but the metafictional techniques and original spins on traditional tropes familiar to me from previous encounters with Park’s work are all present and deployed to superb effect. In ‘A Conversation with the Author’ for example, what starts out looking like exactly what it says in the title quickly morphs into a surreal interrogation scene, in which the titular author is subjected to far more than just the standard interview techniques as the questioner attempts to wrest from him his professional secrets:

‘Let me sum up,’ I said. ‘According to you, the study of fiction writing is important to literary scholars, or might be if they agreed with you. The techniques of your discipline are important to essayists, or might be if they studied them. In addition, you have noticed many ancillary benefits. But the one thing you cannot claim is any improvement to your students’ work. Would that be a fair assessment?’

And then after a moment: ‘Why do you think that is?’ This is how quickly the cancer spreads. I was curious despite myself.

And like many people in his situation he seemed eager to speak, to take me into his confidence in order to improve his chances. Though perhaps he had been storing up some venom for a long time. ‘Because it’s based on lies! The things we teach people, it’s not what we do! No writer in the world takes our advice, or at least no good one. Plot, idea, character, tone, voice, setting, description, exposition – no one thinks about those things. It is a vocabulary invented by idiots to describe concepts that don’t exist. No one has any ‘ideas’, and if they do, they’re a waste of time. Once you start asking yourself how to do something, you can’t do it anymore.’

Glorious, hilarious, and never a truer word. Other stories in the volume include the densely knotty ‘A Resistance to Theory’ in which a scholar attempts to investigate the death of her supervisor literally through the theories of the linguistic philosophers she is studying. How Park manages to sustain this I have no idea but it’s brilliant. Still more brilliant is that the story is also a riff on Buffy the Vampire Slayer. For a (slightly) more traditional science fiction story, ‘The Microscopic Eye’ is both ingenious and moving – a perfect demonstration of Chiang’s conceptual breakthrough theory in just a few pages. Reading Park always leaves me both full and hungry for more – and there’s enough in this short book to engage the mind and the imagination long after reading.

For one final recommendation from my reading this week, please turn your attention to an essay by Rob Latham in the Los Angeles Review of Books. Amidst the slew of pandemic and post-pandemic reading lists, think pieces and calls to arms, Latham’s ‘Zones of Possibility: Science Fiction and the Coronavirus‘, which examines George Stewart’s 1949 science fiction classic Earth Abides within the context of the present moment, stands out for its clarity, intelligence and knowledge of its subject matter, not to mention the fact that it is beautifully written.

‘And this is what science fiction as a genre has to offer us: not blueprints for specific futures, but rather a radical openness to change itself, a willingness to shed old habits and expectations and embrace the new,’ Latham says towards the end of his essay. One of the stranger phenomena – though perhaps not a surprising one – that has come to define these weeks and months is an upsurge in popular interest in science fiction, a curiosity about what science fiction might have to tell us about our current predicament. I hope this interest and curiosity will be lasting, one of the things we bring with us as we move out of lockdown. A willingness to ask questions, and to look in new places. To see where the limits are, and push beyond them.