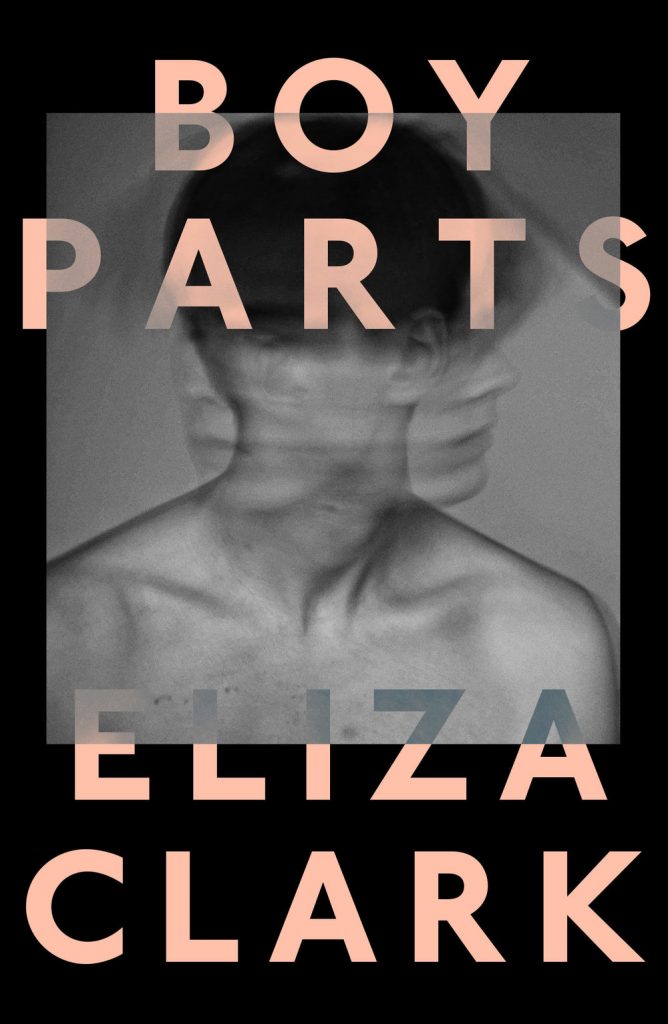

I read this and I thought: this book should win prizes. This book should be at the very least longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction. But I bet they’re not brave enough.

Irina Sturges is a photographer. She studied at Central St Martins and then went on to do a postgraduate course at the Royal College of Art. She found her time as a student in London confronting, confusing, exhilarating and ultimately destabilizing. She has an eating disorder, a coke habit and a very guilty conscience. She has been passionately in love yet determined to sabotage her own happiness. She finds it almost impossible to relate to people other than by exploiting them. Back home in Newcastle, she is doing fairly OK professionally through online sales and her edgy, transgressive imagery has brought her a massive Instagram following. When she gets a call from a gallery in Hackney interested in putting on a retrospective, Irina goes into a tailspin, belief in her work vying with the ever-present, ever corrosive urge to self-destruction. As she sorts through her back catalogue of images, we gain insights into her process, as well as glimpses of the terrible act that brought her to this point of imminent crisis.

What’s to say about this excoriating, impassioned, incisive debut other than go read it? Is it possible for me to say I liked Irina? Put it this way, if I’d lived in a student house with her I would have been the tedious bore making cups of tea, scrubbing the KFC stains off the carpet, putting out the bins and banging on about how she should be eating proper meals. Her work though I get, her intelligence I respect, her ambition I admire. While there will be some who read Boy Parts and understandably feel repelled by Irina’s abrasiveness and misanthropy, for me the most horrific part of what can often be an uncomfortable narrative to read is what happens to Irina at the gallery and afterwards: her experience of marginalisation and eye-watering prejudice, her own uncertainty over the crime that might be a delusion, a fundamental break with reality brought on by mental and emotional collapse.

What actually happened? There are clues but they are inconclusive. Like all the most satisfying novels, Boy Parts leaves us free to make up our own minds. Whatever else this novel is, or might be, it’s a brilliant dissection of objectification and how women making art, especially women from disadvantaged backgrounds, are perceived. Clark’s loose, colloquial style is both a perfect evocation of a particular zeitgeist and a cannily contrived screen for some excellent examination of artistic process and superbly evoked weirdness.

Boy Parts is bold and dark and strikingly ambitious – just like Irina. It is also very, very funny. I loved it a lot. I’m already looking forward to whatever Clark dreams up next. In the meantime, you can find out more about the background and inspirations for Boy Parts in this author interview.