alligators – an effective little story, even if it isn’t particularly original. Russell is haunted by a recurring dream in which he sees his father falling, headless, into a quarry pit. The pit exists – his father used to take him and his brother Tommy on hikes there when he was a kid – but his father’s death was prosaic by comparison – cancer – and no one ever fell into the pit so far as Russell knew, those were just rumours. When an ex-girlfriend sends him a Fortean magazine with an article about the pit, citing its supposed connections to Satanic ritual, Russell decides to lay his ghosts once and for all. Pity he decides to take his two young daughters with him…

alligators – an effective little story, even if it isn’t particularly original. Russell is haunted by a recurring dream in which he sees his father falling, headless, into a quarry pit. The pit exists – his father used to take him and his brother Tommy on hikes there when he was a kid – but his father’s death was prosaic by comparison – cancer – and no one ever fell into the pit so far as Russell knew, those were just rumours. When an ex-girlfriend sends him a Fortean magazine with an article about the pit, citing its supposed connections to Satanic ritual, Russell decides to lay his ghosts once and for all. Pity he decides to take his two young daughters with him…

The sexual politics of this story are pretty dodgy – poor Russell’s had to ‘settle for’ his wife Wendy, who spends too much time being a mathematician and who also isn’t Navajo enough for his taste (having been adopted and not grown up on the Rez, presumably). He spends his idle moments lusting after Cassandra Manygoats, who was raised on the Rez and is also ‘single and hot as hell at 26. And oh, those legs. Not to mention that ass!’. Also. Russell’s mom is so racist she’s a walking cliché. It would help if Russell’s petty self-centredness were tied in more firmly with his eventual fate, but the connection isn’t made clear enough for us to be certain it’s what the author intended. More subtle characterisation would have been a plus all round. Never mind, though – the story is compelling, drawing you inexorably onward towards the inevitable denouement. This is where Nicolay’s writing is at its best, with his genuinely atmospheric descriptions of the ‘Satan pit’ showcasing some first rate use of language:

Across the pit he could see the phrase from the Weird NJ photo. The ‘T’ in ‘MEAT’ had faded some, and now resembled an ‘L’. The quarry walls were mostly pinkish, but nearer the top, rainwater had darkened long streaks to a muddy rose. Stretches stained by the black surface soil had the look of deep crusted burns or wounds. Faded boreholes marked the exposed rock surface at intervals. Nearer the water these scars were fresher and closer together. In some places, they looked very fresh.

Good opener.

The Bad Outer Space – a short piece told from a child’s point of view. Child plays in park with (possibly imaginary) friend Sari, who teaches him how to see the ‘bad outer space’. Kid’s mom is messing around with bad men. Kid’s other (real) friend Vincent disappears suddenly. A deftly written short, but predictable and not really in a good way. More embedded misogyny. I don’t tend to like the child’s PoV trick unless it’s genuinely original (see Scott Bradfield’s brilliant first novel The History of Luminous Motion). ‘The Bad Outer Space’ reads like any number of similar magazine stories – nothing really wrong with it, but it didn’t do much for me.

Ana Kai Tangata – After a bad experience in New Mexico, spelunking enthusiast and archaeologist Max heads to Easter Island, tagging along as part of an expedition dedicated to researching the invertebrate life of the island’s cave systems. As with any small and isolated group, tensions between the various parties soon begin to escalate. Max feels himself very much the unpopular outsider. He is also still haunted by what happened to him – or more specifically what happened to his friend Brant – during his previous expedition, and finally confides in Cassie, whom he has the hots for:

He looked at Cassie across the table. Gray-green eyes, golden brown hair that curved into the base of her neck, lean, hard body below. Tits small, but high and hard. Yeah, he could tell her everything, anything. Fuck it.

Because of course the size and relative firmness of your tits is bound to be directly indicative of how good a confidante you are. Anyway, Easter Island seems to be having a weird effect on Max generally. Max’s friend and caving mentor Altazor has a theory about that:

“There is something very strange about this island, something no one has touched on, at least not in print. It changes everything: people, animals, even plants. What grows here tastes different from crops on other islands… I think there was something here before, something older than the Polynesians… This is something not human, something down in the substrate, in the very bedrock, down below the halocline where the salt water meets the fresh.”

There is a very nice sequence about almost getting lost inside a cave, and the fugue state that overcomes Max in the immediate aftermath of that experience is superbly rendered. On the whole though I found this story unsatisfying. Easter Island is made to feel like a convenient backdrop, an almost incidental exotic location for a pretty run-of-the-mill Elder Gods-type narrative. If there had been more focus on the invertebrate study – something to give any kind of genuine perspective on the island – this weakness might have been ameliorated. More women problems, and Max never really becomes interesting enough for us to give a damn about him being chased down by a giant trans-dimensional woodlouse at the end.

On the level of craft and readability the story is fine – I enjoyed it plenty. I think at least some of my adverse criticism is coming from the fact that this collection has been over-hyped, and I was expecting something vastly original as a result. At this stage, I’m finding Nicolay to be a solidly competent and highly readable writer with a good feel for language – but there’s nothing ground-breaking here in terms of subject matter or formal approach, at least not so far.

Eyes Exchange Bank – This is a weird one. After being dumped by his girlfriend Lisa, Ray journeys to the town of Lansdale to see his old mate Danny – he reckons they’ll have a few beers, talk about old times, set the world to rights. When he arrives though, things seem far from well. First he has a near-accident and damages his car. Then Danny – and Danny’s apartment – don’t seem at all as he remembered them. The town itself is horrible – a dead zone, depopulated and shot to shit. They head off to the mall for a pizza and (hopefully) a bit of action. Ray gets plenty of action, all right – but he sure ain’t coming back for more. Of anything.

For much of its length this story reads like an anxiety dream, and the gradual accumulation of sinister details and small things going wrong reminded me of Ramsey Campbell’s stories. Ramsey always nails a mean ending though, and in this case at least that is one thing Nicolay doesn’t do, relying on zombies ex machina to deal the killer blow. The ending fits the atmosphere, in a way, but there’s so much disjuncture here, and not in a good way. All the stuff about Poe feels like stage dressing, with the ‘premature burial’ tacked on opportunistically without having been earned. Is Danny a zombie too now? He tells Ray he has a ‘whole new way of seeing things’ – courtesy of his visits to the eponymous Eyes Exchange Bank, no doubt, but once again the idea feels half-baked.

There seems to be a theme developing here: some nice writing, a good sense of place, but with a hollowness at the centre that leaves you feeling cheated.

Phragmites – Austin Becenti is an archaeologist and a caver. His holy grail is the mysterious Cave 34, tucked away in the mountains along the Arizona-New Mexico state line and inaccessible as fuck. An archaeologist named Earl Morris discovered it in the 1920s, but he never wrote up his report and so far as anyone knows he never went back. All researchers have to go on are the seven human skulls Morris brought back with him, each of them displaying the marks of what looks like trepanning but can’t be – no one was into trepanning, not there, not then. When Austin receives a phone call from his cousin Dennison, telling him he’s found the cave and is willing to lead Austin to it, our intrepid explorer thinks the offer may be too good to be true. There’s bad blood between him and Dennison, who holds him in contempt for abandoning his Navajo heritage. Plus there was some trouble over a woman. Cave 34, though – how can Austin resist? And when he pulls up in the parking lot of the McDonald’s out by Shiprock, his cousin seems friendly enough. It’s a nice day, too. Everything’s looking good, and Austin’s almost prepared to let bygones be bygones. Trouble is, Dennison isn’t…

Well, this is a cracker. The sense of place in this story is scintillating, not to say resplendent. Here at last is the wealth of specialist detail relating to geology, landscape, even caving equipment that I would have welcomed more of in ‘Ana Kai Tangata’. Even the lead-in episode in the dodgy motel is brilliantly effective, and once we get into the endgame there is some solidly breathtaking writing on display:

The high pines gave way to open space, several broad ponds of lingering snowmelt sprawled across a shallow depression, every pool way more full than normal this late in the year. Dennison chose a route between the ponds and Austin followed. The entire basin must’ve been flooded in the spring since the ground was crazed with mud cracks, the thin interlocking crusts crumbling to dust beneath their steps. Jagged bands of leached alkali spread out around each pond. Approaching one he saw dead brown weed choking the wide lens of stagnant water, ranks of fuzzy fronds straining to reach the surface yet failing, the still pool fixed as a vast decrepit moss agate, dismal exercise in vegetal futility.

There’s loads of stuff like this, all of it directly relevant to the story, anchored to it with the strongest kind of caving rope, and Nicolay works tirelessly to make every detail count. Admirable, brilliant stuff. Austin and Dennison’s final miracle-nightmare traverse of the sheer rock face that is the only means of accessing the cave left me breathless with vertigo. When a writer pulls off a stunt like this it’s wonderful to see. Of course, we can make a solid guess at the ending as soon as we learn – pretty early on – that the Navajo name for Cave 34 is ‘the spider’s cave’ or something like it. But so what if we can see the monster coming? I enjoyed this story way too much have it spoiled for me by an ending that would be exceptionally difficult to navigate perfectly, in any case.

I started off thinking it was a miscalculation, to have two long stories about caves in a single volume, but ended up feeling just the opposite, that this kind of fixation is actually a selling point, rooting the drama in the writer’s own personal obsessions and areas of expertise. I loved it that there was a continuing character – a walk-on part for Altazor, whom we last saw hanging out in a bar and spinning yarns in ‘Ana Kai Tangata’, and who here, we learn, was also Austin’s adviser at UNM. ‘Too bad Altazor’s gone,’ Austin reflects. ‘He left UNM ’cause of some kind of scandal. Never found out what it was. He was just gone one day and no one would talk about it.’

It would be nice – it would be very nice – if Nicolay were to consider including even a single female character who didn’t slot into his ill-conceived archetypes of whore, bitch or eye-candy (frequently all three simultaneously) but that depressing caveat aside, ‘Phragmites’ is a great piece of writing.

The Soft Frogs – Jaycee used to be a bug nerd. Now he’s a fake punk with severely diminished college prospects, a rank day job and an insatiable sexual appetite. His favourite hangout is the Melody, a club with legendary music credentials and an ever-circulating supply of willing female company as an added bonus. Here he meets Eileen – a potentially interesting woman character at last from Nicolay, but no, wait, she turns out to be a monster. Literally.

Environmental pollution meets body horror meets boring male entitlement. Trite, slight and obvious. Honestly, Jason, you were far more interesting when you were a bug nerd. Ah well, too late now. Those damn frogs…

Geschaefte – Once again, we encounter almost (Ramsey) Campbellian twists of fate and truncated futures as we follow Cal into a hell of his own making. Or is it? Calvin is a college student, obsessed with setting up a poetry magazine to honour and emulate his hero, Jack Spicer, the poet of unknowing. Like other Nicolay ‘heroes’, Cal is a rampant misogynist and a bit of a scumbag. His odiousness finally catches up with him when his girlfriend Risa dies on Thanksgiving, in her parents’ garage, in circumstances that are more than just a little bit Cal-related. Consumed by guilt and self-pity, rejected by his family and unable to continue at college, Cal finds himself couch-surfing his way around the western United States, eventually ending up in the San Francisco apartment of a reluctant comrade, Jerrod. How did Cal first meet Jerrod? He can’t quite remember, and there’s weird shit going on in the apartment across the hall. As Cal’s perceptions become more twisted, so does the version of reality that envelops him. The stench of decay and bottled piss (read it and see) is tangible. We sense that things will not end well for Calvin, and they don’t.

The odd overwrought metaphor notwithstanding, this is one hell of a well written story. The Spicer connections – the unknowable nature of poetry, voices from the beyond (check out the link) – make ‘Geschaefte’ all the more fascinating and add an extra layer of meaning. As a study of mental breakdown, as a horror story, the piece is equally riveting. Of course, we have to put up with copious amounts of stuff like this along the way:

Whatever it is that clicks had clicked for him. Despite horn-rimmed glasses she wore as if actually shooting for the mousy look, her wide, bright eyes and her long, dark hair were anything but plain, and her worn grey sweater swelled with its high hard brace of tight bound breasts.

But then just a few paragraphs later we have this little snatch of brilliance, and plenty more besides:

Cal’s consciousness drifted fitfully down into REM with the rhythms of some flat hulk of marine debris seesawing into the depths. Soon he found himself as usual, in a sterile simulacrum of his current setting, dreaming he was laid out on the futon, dreaming he was dreaming. But then his vision inverted, so that rather than a lifeless replica of Jerrod’s apartment, he occupied a gray lit void in the shape of his own form. Within it he was become a diminished thing, size of a small bird or large insect, suspended somewhere in his own hollow and heartless torso. The lost moth of his soul blatted about the emptiness inside him, at first more disoriented than panicked, though a feeling of entrapment took hold of him almost at once.

I get it – or at least I think I get it: Cal is an appalling man-child and gets what he deserves. But I can’t help thinking – and I have to say I’m thinking it all the time as I read this collection – that the stories would work even better, would be more satisfying, more devastating, more intellectually rigorous, more artistically powerful, if Nicolay could bring himself to feel even a passing interest in the idea of women entering the narrative as characters rather than sex-toys. There’s a truly great, timeless story here in ‘Geschaefte’ just waiting to happen. and it wouldn’t take much tweaking. As it is, we feel too easily justified in giving Cal the finger and moving on. Which is a shame – again – when so much of the writing here is so good.

Tuckahoe – What is it with weird fiction and cops wandering into stuff they don’t understand?

Not our luckless Sergeant Howie this time, but Detective Donny Cortu. Like our favourite Scottish policeman before him, Donny has happened upon something strange and is determined to get some answers. Had he known what kind of answers he was going to get, he may never have started his investigation in the first place…

Donny Cortu is a police detective. Following a shady incident involving witness protection, he’s been seconded to the backwoods of South Jersey, where instead of solving complicated murders, he spends his days picking up the pieces (literally) at the site of road traffic accidents near the nothing town of Tuckahoe (also a Native name for a species of edible underground fungus – this will become relevant later). Donny desperately wants out of there. He wants to regain the trust of his wife Martina. He wants job satisfaction. When a mysterious extra appendage (stick with me here) is brought in as part of the carnage from Tuckahoe’s latest highway fatality, Donny seizes the chance to investigate. His search leads him first to Carlsen, a cop from another squad room who has a bizarre story to tell, and then out to the broken down homestead of the inbred Storch family, which Donny comes to believe may harbour something more than ornery locals with a personal hygiene problem.

Guess what? He’s right.

Nicolay may well have stuck to his personal dogme in the strictest sense by not mentioning Cthulhu or Innsmouth or any other Mythos stuff by name, but Tuckahoe is pure Lovecraft, of course, with ‘The Dunwich Horror’ as its incestuous cousin. Not that this matters. ‘Tuckahoe’ is as engrossing and entertaining as it is predictable, with the partial use of the ‘club story’ format working perfectly to its advantage. Whilst I might quibble with the use of ‘ick’ and ‘glop’ as nouns outside of dialogue, this is a small gripe. The writing here is as polished and compelling as elsewhere in this collection, and how many words for repulsively oozing substrate are there anyway?

I was also extra-excited by this story, as I thought for a moment we might have an actual woman with an actual speaking part. Alyssa Campion may only be the pathologist’s assistant, but she’s certainly no shrinking violet when it comes to handling body parts. We might infer from this that she would have no problem telling a leering womaniser like Donny Cortu where to sling his hook, but what’s this?

“May I ask you a question, Detective?”

“Sure, go ahead.”

“Are you a faggot, Detective? Are you gay, or is there something else wrong with you?”

Donny spluttered at the receiver – “Hey! Waitta – ” – but she plowed ahead.

“You don’t act gay, but I don’t know, maybe it’s different for cops. But if you’re straight, maybe you can tell me why I waited the whole damn morning for you to put the moves on me and that creepy old man does it instead… Was that some kind of stunt you two worked out together? Because if it was I didn’t think it was very funny.’

Oh Christ, tell me this is not going to be some kind of sexual harassment suit. For once he’d controlled himself. He hadn’t even hit on her – that was all Bilo. “No! No. Nothing like that. It’s just -.”

“Yeah sure. Whatever. So now you’re going to make a girl do all the heavy lifting? I guess it really is true that chivalry is dead.”

Oh dear. This is wrong, not to say vastly embarrassing, on so many levels. And of course Alyssa turns out to know a hell of a lot more about the Storch place than she initially lets on.

This is the longest story in the book – it’s almost a short novel – and although it could easily be argued that it’s too long – altogether too many people telling other people what they heard once from someone else – I wouldn’t agree. I always enjoy stories like this, wheels within wheels, and this one rolled along for me without ever dragging.

Even so, though, ‘Tuckahoe’ could have been so much better – like all the other stories in the book – if Nicolay had refrained from piling on the dudebro attitude. It’s so repetitive, so dull. I know horror is supposed to be transgressive – but unfettered misogyny isn’t transgressive, it’s just tedious.

Am I beginning to see an attempt at a weird kind of inverse feminism at work in Ana Kai Tangata? All Nicolay’s protags are sexist arseholes, all end up devoured by forces from the beyond. In ‘Tuckahoe’ there’s even a (wholly unconvincing and uncharacteristically clunky – did someone persuade Nicolay to put this in, thinking it might help to ‘explain’ the general dudebroness?) monologue by Alyssa, talking about how it’s impossible to be a woman and survive around these parts without turning misogynist.

There are better ways around the problem. Such as writing women into the story properly and actually giving a damn about them being there.

*

Ana Kai Tangata is a good collection. All the stories, to varying extents, are intense and highly readable – it was never a hardship to return to this book and I frequently found myself mentally taking my hat off to the author for one ingenious reversal or another. The writing is of a consistently high standard and veers close to brilliance on many occasions. There are enough hallmarks of genuine originality – the caving, the arid, imposing landscape of New Mexico – to persuade me that Nicolay is deadly serious about his craft, enough for me to genuinely look forward to seeing what he writes next. (Psst – I hope it’s a novel. Nicolay’s story arcs lend themselves naturally and instinctively to the longer length, and I seriously think that this writer could pull off that rare thing: a full-length horror story that sticks the distance without dissolving into cliche.)

The one major downside – and excuse me for sounding like a broken record here – is Nicolay’s seeming inability to write about women. I wouldn’t mind so much if he simply admitted to himself that this was a weakness and stuck to writing bro-on-bro standoffs instead. (It’s no coincidence that in the most all-round effective story in this volume, the superb ‘Phragmites’, Nicolay is sensible enough to leave the women out of it.) Thinking about this issue, and judging by the all-round quality of the stories otherwise, I THINK what Nicolay is trying to do is offer some kind of commentary on the toxic nature of macho masculinity. You could say he succeeds – there’s certainly enough of it on show here. But to be a commentary, rather than simply a roll-call, we need more: more indication of intent on the part of the author, more subtext, more counterpoint. There is literally no counterpoint, and for me at least Ana Kai Tangata suffers for the lack of it. For the most part, I was able to set my grievances to one side – I was enjoying myself too much not to, and on the up side there ARE giant transdimensional man-eating woodlice on hand to dispose of some of these scumbags – but I would understand completely if other readers felt too pissed off by the general arseholeism of Nicolay’s characters to want to continue.

Would I recommend Ana Kai Tangata as a collection? Yes definitely, but with those caveats. And in the hope that Nicolay will work on these problem areas to produce an even better book next time out.

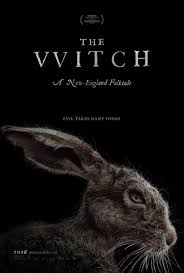

Well, this was interesting. I’d been looking forward to The Witch ever since seeing the trailer around this time last year. I missed seeing it in the cinema but finally caught up with it on DVD, a perfectly acceptable substitute when the need arises, but the unnerving, subtle beauty of the cinematography did leave me wishing I’d been able to experience this movie on the big screen as the director intended.

Well, this was interesting. I’d been looking forward to The Witch ever since seeing the trailer around this time last year. I missed seeing it in the cinema but finally caught up with it on DVD, a perfectly acceptable substitute when the need arises, but the unnerving, subtle beauty of the cinematography did leave me wishing I’d been able to experience this movie on the big screen as the director intended.